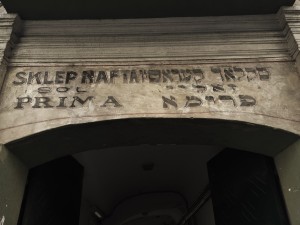

We don’t discuss the echoes

The multilingual facade of this oil shop fades over time after the anti-Semitic violence devastated Vilno’s Jewish population

By Farrell Brenner

As a patrilineal Jew and a student of women’s and gender studies, I’ve been reeling with questions over the past two weeks. I felt deep in my body the collision between a struggle with authenticity and a burden of responsibility. In many of the places we visited in Vilno, Lithuania (a city once called the Jerusalem of the North), the residue of the Jewish feminine—or even simply the feminine Other—lurked on gravestones, behind trees, in pits where whole cities were immolated. I can’t say quite how I know so intimately the story of destruction that has been etched (often literally) onto skin. But I also won’t reduce this knowledge to me being hypersensitive or excessively empathic; that is just one way emotional labor is feminized and devalued, when it actually carries great significance for the vitality and memory of communities. There were moments—in the only remaining Vilno synagogue (there were once over a hundred), at the mass graves of Panerai, in exhibits that closely resembled shrines—when an understanding of survival and devastation rose from dormancy to my throat and sat there like a lump. I must have learned it over meals or at holidays or in bedtime stories, though these words were never stated explicitly. We don’t talk about the ways that the trauma of one generation is cradled, cultivated, and bequeathed to the next. We don’t discuss the echoes.

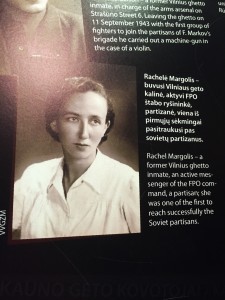

“Rachele Margolis – a former Vilnius ghetto inmate, an active messenger of the FPO command, a partisan; she was one of the first to reach successfully the Soviet partisans.”

Likewise, the struggles particular to women during the Holocaust were not at the forefront of many of our visits and discussions. Timothy Snyder presents the killing of Jewish women and children in the sixth chapter of Bloodlands as an indicator of the progression of Nazi brutality in the Final Solution, rather than as an integral component of the destruction of the Jewish people. As another example, the compulsory abortions at the Vilno Ghetto hospital are not merely a rhetorical device to describe the cruelty of ghetto conditions; they are at the core of the story of extermination, but have been decentered in the historiography of the Shoah. I was surprised—pleased and troubled all at the same time—that this specific gendered phenomenon was mentioned on our tour of Jewish Vilno (on our general tour of the city later that day, we sometimes stood on top of cemeteries without so much as mentioning the bodies beneath our feet).

As I begin my research on the women couriers and smugglers of the Polish ghettos, I am amazed at how easily their work (resistance that ranged from fighting in uprisings to delivering life-saving materials to boosting morale) has been defined as peripheral, passive, and less valuable. Indeed, the dehumanization of Jews via the norms of anti-Semitism carried with it a de-gendering as well—I am reminded of the work of Angela Davis, a Black feminist scholar and activist who wrote in Women, Race, and Class that female slaves in the United States were simultaneously exploited as genderless chattel, and also as specifically feminine entities (1981). While I am not equating these two genocides, it becomes clear that gender and sexuality are flexible sites of great violence in the context of ethnic cleansing. The following three poems contemplate the ways that sexual and gender-based violence have been written onto the bodies of Jewish women historically and contemporarily, though these themes are often written out of the most important texts of the Holocaust. In the last piece, the italicized lines are quoted from David Patterson’s chapter “The Nazi Assault on the Jewish Soul through the Murder of the Jewish Mother” in Different Horrors / Same Hell: Gender and the Holocaust edited by Myrna Goldberg and Amy Shapiro (2013).

On Assimilation

when she sits in crowded ovals of gender survivors

(you see, circles are, in their radial perfectness, for the unadulterated)

there is a creeping, a catch,

the shame the shame the shame

too dirty, too ugly, too many cattle cars full

i used to guard these gates until i was swallowed, and locked inside

she too would rather be silent than sift through ashes and lye

and risk declaring to gentility another way we have been crushed beneath boots, defiled beneath fluorescent lights

when in reality she should know that

odds are

her fathers’ aunts, sisters, their daughters…

You, fill in the blanks

i have

frost-bitten fingers,

frozen tongue

it’s the price paid for survival

which is not the same as liberation

a taste

she still anticipates

though i am often told by men with pitying, milky eyes framed by jaundiced cheekbones

that we were cradled and nursed in the embrace of a more fertile, more beautiful lady

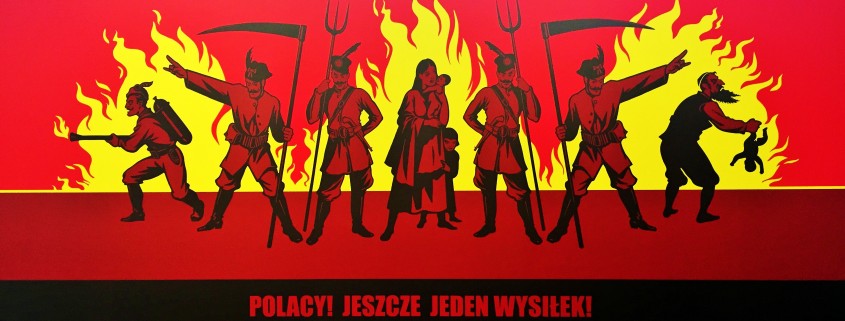

i suspect her torch was a scythe, her breasts armor, her nails ferrous and venomous

another soldier in disguise, holding us at firearm’s length

but now the gun is warm and honeysweet and smells like freshly printed paper

We ate that gun, devoured it in three bites

and it resides deep in our bones

still today

Autopsy of a Jewess

ribs have erupted through the thin skin scrim, reaching out to the moon

why have you forsaken me

yet hips bumpin, the nectar of a sweet honeyflesh that, hushing, smothered

with great flower comes great responsibility

keeper of the keys, the brothers, the bread and the dead; clandestine meetings were held in the folds of sinew

when the oil burns out, the flame is sustained by the grease on our elbows

neck, rusted straight by the iron tears of scaled, scalded angels, whose necks themselves were broken in the fall

i don’t even know the first muscle i’d flex in order to avert my eyes

note the tongue, thrice forked, welded back together with vitriolic barbs (a cosmetic surgery)

i can whisper sweet nothings to the boot on my chest in six different languages

uwolnij mnie, haltn mir, deflate these lungs

as i did when i sucked the life out of

let’s pretend they were just balloons

and if the hot air lifts you over the smoldering bricks

out of the burning city, away from here

my last breath will not have been in vain

The legend goes

The legend goes

that the Alsatian mothers threw

their children

with a sick vigor

into the wailing fire

before they could be baptized

before they would be burned, cauterized

and then themselves followed

chins up

necks taught

biting the insides of their mutilated cheeks

Thus the Mishnah teaches that saving a single life is like saving the entire world (Sanhedrin 4:5). In the same verse, it says that to destroy a single life is like destroying the entire world. Where, then, is the mitzvah in killing an infant to save the mother?

In whose hell

does a baptized Jewish baby burn?

Perhaps like Job

there will be a bargain for its soul

How ironic it is

to learn the self, the us

from the cracks in obsidian plaques

and the gaps in peer-reviewed articles

in English

I’ll justify it

somehow

What color ink does one use

to confess the manifestation

of generations of lowered heads

a thirty-year exit from the temple?

If the crime of the Jew is being alive, then the most heinous of criminals is the Jewish mother.

How do you explain to your honey and raisin auntie

How do you kibitz the kibitzer

there will be no child of me

you see

I would be the mother

who threw her child into the fire

before someone else did it for her