Poland’s 1968 Anti-Semitic Campaign: Why Historical Dialogue is Important

By Brigitta Pupillo

When I first arrived in Central Europe I felt very prepared and confident, to the point of almost arrogance. I knew that we would be gaining palpable knowledge about the Holocaust and the broader history of anti-Semitism in Europe, but my initial attitude was “I had already learned much of it before.” I imagined this program was going to be a very emotional experience but I did not predict I was going to be surprised or shocked by anything. I prepared myself to see names, pictures, and houses of people brutally murdered during the Holocaust, however, I was not as prepared as I thought. I found myself dumbfounded in the museum we visited in Warsaw, POLIN, which is dedicated to the history of the Jews in Poland. The depictions of the events of 1968 are what most deeply unnerved me.

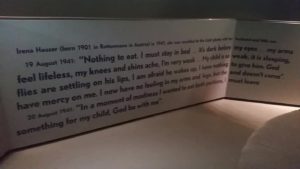

During the two hour walk through the museum, I learned a great deal more about the history and culture of the Polish Jews than I had previously known. The creators of the Holocaust exhibition definitely wanted to make the experience of walking through their installation both informative and emotional. I distinctly remember an entry painted onto the grey wall of a sitting area from a diary of a mother trapped in one of the Ghettos desperately worried that her baby would starve. This was a difficult section of the museum to pass through, but it was not the end. Usually the Holocaust, at least how I have learned about it before, is the end of Jewish Polish history so I sort of expected the museum to also end at the Holocaust. As I left this section of the museum, I encountered a wall of televisions. The screens transmitted a speech made by the head of Poland’s ruling Communist Party leader in the 1950s and 1960s, Władysław Gomułka. I remember him encouraging “Zionists” to leave the country, the way he talked was disturbing and that there was underlying intentions. In the context of POLIN’s exhibit, this snippet was meant to represent Poland’s 1968 anti-Semitic campaign, during which anyone of Jewish origin (publically referred to as “Zionists”) were persecuted for political and social reasons. This campaign shockingly took place only 25 years after the Holocaust and deployed propaganda tactics similar to those in Nazi Germany.

During the two hour walk through the museum, I learned a great deal more about the history and culture of the Polish Jews than I had previously known. The creators of the Holocaust exhibition definitely wanted to make the experience of walking through their installation both informative and emotional. I distinctly remember an entry painted onto the grey wall of a sitting area from a diary of a mother trapped in one of the Ghettos desperately worried that her baby would starve. This was a difficult section of the museum to pass through, but it was not the end. Usually the Holocaust, at least how I have learned about it before, is the end of Jewish Polish history so I sort of expected the museum to also end at the Holocaust. As I left this section of the museum, I encountered a wall of televisions. The screens transmitted a speech made by the head of Poland’s ruling Communist Party leader in the 1950s and 1960s, Władysław Gomułka. I remember him encouraging “Zionists” to leave the country, the way he talked was disturbing and that there was underlying intentions. In the context of POLIN’s exhibit, this snippet was meant to represent Poland’s 1968 anti-Semitic campaign, during which anyone of Jewish origin (publically referred to as “Zionists”) were persecuted for political and social reasons. This campaign shockingly took place only 25 years after the Holocaust and deployed propaganda tactics similar to those in Nazi Germany.

When trying to make sense of it all I reflected back on the numerous conversations we had been involved in during our travels with members of organizations who work on reconciliation and the remembrance of Jews. At some point they had all mentioned that there was a silence shrouding the Holocaust in the post-war years, and many expressed how they still face obstacles in trying to commemorate Jewish history. This silence is clear in the context of POLIN itself, which only opened two years ago, in 2014. I feel like POLIN was such a critical experience because it embodied the importance of the educational work of the organizations we’ve come in contact with as well as the importance of the education I am receiving here. Through the grassroots work of the organizations we have visited, the activists are attempting to overcome the consequences of closing the door on the past. By turning away from the past, we are allowing for the same old prejudices to adapt and reemerge.

The anti-Semitic campaign took place primarily in 1968, but its origins reach back to the 1940s. Gomułka as well as the other leaders of the Poland’s Communist party were charged with diverging from the party platform and were placed under arrest; they were replaced by a group with high profile leaders, many of Jewish origin. Although Gomułka regained a leadership role in 1956 after being released from prison, internally the party remained split into the reformist Puławy group made up of many Jewish leaders, and Gomułka’s own Natolin branch of the party. It doesn’t take much to connect the dots; running an anti-Semitic campaign would be a political power move for the Natolin members to gain control of the party.

The anti-Semitic campaign took place primarily in 1968, but its origins reach back to the 1940s. Gomułka as well as the other leaders of the Poland’s Communist party were charged with diverging from the party platform and were placed under arrest; they were replaced by a group with high profile leaders, many of Jewish origin. Although Gomułka regained a leadership role in 1956 after being released from prison, internally the party remained split into the reformist Puławy group made up of many Jewish leaders, and Gomułka’s own Natolin branch of the party. It doesn’t take much to connect the dots; running an anti-Semitic campaign would be a political power move for the Natolin members to gain control of the party.

However, the real trigger of the campaign was the Six Day War between Israel and Arab countries in June of 1967. Backed by the Soviet Union, official support of Poland’s Communist government for the Arab countries was made known through the party-controlled media, which unambiguously painted Israel as the aggressor in the war. Gomułka’s televised speech to the Trade Union Congress on June 19th, 1967 was intended to send a signal to the state security apparatus to start the campaign, which began by the searching out people of Jewish origins working in government and other major organizations, claiming they were supporters of Israel.

The campaign against the Jews increased in 1968. In March and April, groups of students, workers, educators, and intelligentsia, protested the authoritarian practices of the Communist government. While the government fiercely suppressed the protests by imprisoning activists, a smear campaign was also set in motion; the government published propaganda that either labeled the leaders of the protests as Jewish or they were said to be manipulated by an international Jewish organizations. From today’s perspective, the propaganda was practically recycled from the Nazis, who also falsely promoted notions of conspiracies lead by international Jewish organizations to create public distrust of Jews.

Jewish leaders were actively purged from government, increasing the power of the Natolin group over the Puławy group. Jewish people were also removed from universities, worker organizations, and from management positions in state-run enterprises, any place perceived as important or influential. Furthermore, like how the Nazis used Jews as the scapegoat of Germany’s failure in WWI, the communist government accused the Jews of being fanatical communists responsible for the horrors of the Stalinist era. Also, similar to how the Nazi’s blamed the Jews for the failure of the economy, using the age old stereotype of the “greedy Jew”, the Polish government spread the idea that Jews were ready to throw their comrades under the bus for the American dollar. It wasn’t just government leaders who benefited from anti-Semitism; every day citizens were frustrated with the poor working conditions and their livelihoods in Poland but were not allowed to criticize the government. However in 1968, in the context of the campaign, they could criticize some members of society, those members who happened to be Jewish. This gave citizens an outlet for their frustrations. Jews as scapegoats wasn’t completely original. Nazi Germany also painted Jews as being traitors of the country and many Germans got a cathartic release of frustration of the post-WWI society by identifying a group to place their hate onto. At the high point of the campaign Jews were stripped of their citizenship and given one-way travel cards and told to leave. Considering the social and political conditions in Poland in the aftermath of the Holocaust, many did so voluntarily. The campaign is considered to have ended in April of 1968, but the total numbers of people who took the one-way cards and emigrated in 1967 was 3,437. However the campaign still had lasting effects because in 1969 was 7,674 emigrants. These people tended to emigrate to Israel, America and Western Europe where they had friends or family.

I want to stress that though Poland’s anti-Semitic campaign was awful, it is not at all comparable to the tragedy that was the Holocaust. The point in analyzing these events in tandem is to see how the same old prejudice and persecution can keep remerging and adapting itself to new environments. Gomułka did hear objections to the campaign, from a very small group of its victims – friends/family members of the victims and a handful of others which prompted him to try to reign the campaign in. Of course his attempts were only made after he had reached his goals and the damage was already done. In a post-Holocaust society there were certain lines that could not be crossed. However, Gomułka and his colleagues stood right at that line. If they had told Jews to get out there probably would have been more outcry and attention, but they didn’t, they used the word “Zionist”, so they could play everything off as merely politics with no underlying racial prejudice. The language is still one of discrimination, but it adapted itself to fit within the new post-Holocaust context. It is still disturbing that an event like that took place at all, let alone only a two decades and a half after the Holocaust, a period when one would assume there would have been more protest earlier on. I think that part of the answer as to why the campaign was allowed to flourish lies in the absence of a dialogue on the Holocaust in the post-war years.

Reflecting back on our trips through Poland and Lithuania there has been a motif of silence surrounding the Holocaust. The Borderlands Foundation, Grodzka Gate, Lost Shetl have made outstanding progress in commemoration and remembrance of Holocaust victims however they had a lot of work to do. Dialogue on the Holocaust only really opened up in 1989, before that the Holocaust was something not really discussed both in private contexts and on a broad society level. Children of the survivors of the Holocaust had questions for their parents and grandparents but they didn’t get answers. At a social level Jewish history was, and in some ways still is, treated as separate, overshadowed by a dominating national narrative. For the people of Poland starting in the communist era, the story of WWII was that six million Poles died; mentioning that half of them were Jewish was a mere afterthought. There was definitely no talk of incidences where Polish people took an active part in the killing of their Jewish neighbors. These topics are uncomfortable but confronting them gets at the roots of prejudice and can stop it from remerging.

I would like to point out the Borderlands Foundation and their work specifically in Sejny. Sejny used to have a thriving Jewish population, all of them are gone now. The Borderlands Foundation, however, works to keep the Jewish history alive through preservation, commemoration, and most of all education. They typically work with children and by teaching them about Jewish history and culture, they teach children to be empathetic, respectful, and peaceful problem solvers. The children come out of the programs continuing the work themselves. One suspects that these aren’t the type of people who would let what happened in 1968 happen now; they have strong convictions on respecting diversity and more nuanced versions of history. Poland is making strides. POLIN only opened two years ago but it is teaching that Polish history is not separate from Jewish history, talking about the benefits of diversity and intercultural dialogue. The entire museum is for Poles and Jews, thus signifying ambition for a more inclusive and respectful society.

Going to POLIN and learning about the anti-Semitic campaign was difficult. Yet it is beneficial to have such an experience that not only epitomizes one of the core themes of the Central Europe program – reconciliation, but in that context, the importance of historical dialogue. It took a long time for Poland to get to a place where dialogue surrounding the Holocaust was not only permissible but encouraged; but since it started there has been exponential progress which is something every society can learn from. When we don’t confront our prejudices they keep remerging and oppressing people. When we face our pasts we not only heal, but become a stronger society.