Warsaw is Rising

By Marcin Zak

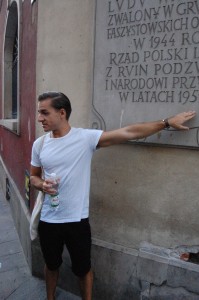

In a perfect world, it would be difficult to say something that hasn’t already been said about the likes of Warsaw and its suffering over the course of the Second World War. Having now been there myself and experienced its history a little bit, I’d say that time has not necessarily done full justice to the memory of the city as a place of unspeakable tragedy. It seems that only quite recently has the focus on its painful past become a topic of significant discourse. Though I cannot claim to have examined Warsaw with any considerable depth of vision, perhaps a more cursory glance at the capital city, that of a tourist and stranger of sorts, may offer a perspective that is both something of a summary and a very general view of what makes the Warsaw of today a Warsaw worth re-examining with a historical lens.

Our tour guide, Roch, argued that Polish and Jewish history cannot and should not be easily separated.

As a guest within the city limits, I found that I couldn’t say that it is a place of many cultural contradictions in the way that more Western European cities less affected by the War and more exposed to a variety of cultural agendas since the War are. To my senses, Warsaw is still, even seventy years after the fact, a city where the primary narrative is that of reconstruction. And that reconstruction seems to be strictly from a Polish perspective. There is a newness there that pervades most every nook and cranny of its existence. Even the surviving vestiges of what Warsaw was before the war possess elements of approximation, that is: attempts to preserve the old in ways that can never hope to fully recapture the grandeur and culture of the pre-war capital. They can only be seen as effective reconstructions of a city long lost to the machinations of the Nazis. This has ensured, in my mind, Warsaw’s stature as a city in search of or, more accurately, recovering its identity as an important center of Polish culture.

At the Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego – Warsaw Rising Museum with the “Kotwica” symbol of the Polish Underground.

The Warsaw Rising Museum (Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego) is a testament to the efforts being made to preserve the history of a still fragile urban area. It is a museum with a specific agenda: to imbue Warsaw and its citizens (and, by extension, the Polish people) with a sense of reverence for those who fought in the Uprising. By all accounts, this is a complete reversal from the historical interpretation foisted upon the populace during the era as a Soviet satellite state. Of particular importance to me is how readily the Polish people embraced the museum and its narrative in 2004, which seems unerringly to posit those who fought in the Uprising as heroes and heroines. And, from my perspective, it seems that they were as such, especially in the face of nearly impossible odds. Though I feel great sympathy with the museum’s narrative, I always feel as though I must err on the side of caution when consuming such narratives. To me, the museum is a shrine to the destruction of Warsaw, and a badly needed one at that. The past, due to communist propaganda and distortion, was seriously in danger of becoming trivialized. In the simplest terms, the museum is an instrument towards raising the past and contemporary historical morale of the Polish people. That said, the narrative cannot be said to be completely unbiased or all-encompassing.

Though Warsaw is in the process of recovering its status as the preeminent Polish city, I feel the same cannot be said regarding its Jewish history. Even today, despite several initiatives to preserve their history and culture (including the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews), the obscurity of the Jews as a defining ethnic group within the history of Poland is surprising. Indeed, the Warsaw Uprising and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising are presented and surveyed as two very distinctly different events. Yes, they both took place at different times in different years but, as our tour guide Roch alluded to, the history of the Poles and the history of the Jews cannot be easily separated and perhaps it is not the most advisable idea to do so, to have a segregated history. Yet the narratives do appear to be segregated in separate museums, no less. The issue now arises of how each group (Poles and Jews) would like to have their respective histories commemorated. Using the uprising as an example: For the Poles, the 1944 uprising was a matter of preserving the existence of an independent Polish state. For the Jews, the 1943 uprising was a matter of preserving their humanity and not going down without a fight. The question remains: How should Polish history be presented in the 21st century? Is Poland ready to ascertain a comprehensive historical narrative? Is it ready to bridge the gap between its contemporary and past cultural narratives? The answer, from my perspective as a traveler and learner, is waiting to be unearthed.