Spaces of Lost Memory

By Charlotte Oestrich

Every country has a past, as does each city and street within it. Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania has multiple layers of heritage and memory considering it once formerly the capital of Poland. This city has been shaped by centuries of occupation and brutal wars, as well as discrimination; like most cities it seeks to bury the negative memories of their past and bring the positive to the forefront. When walking through the streets of the city one can certainly feel the cultural resonance marked by decades of change. One thing that immediately sparked my interest was how the lost community of Lithuanian Jewish people was remembered, as well as what cultural memories remained.

Every country has a past, as does each city and street within it. Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania has multiple layers of heritage and memory considering it once formerly the capital of Poland. This city has been shaped by centuries of occupation and brutal wars, as well as discrimination; like most cities it seeks to bury the negative memories of their past and bring the positive to the forefront. When walking through the streets of the city one can certainly feel the cultural resonance marked by decades of change. One thing that immediately sparked my interest was how the lost community of Lithuanian Jewish people was remembered, as well as what cultural memories remained.

While walking through the streets there are few traces of Jewish memory. So little in fact that you could walk through the city completely unaware that it was formerly a cultural hub for European Jewish culture– known as ‘Jerusalem of the North’. Prior to WWII, Lithuania was home to approximately 240,000 Jewish people, 95% of which were killed during the Holocaust; almost all traces of this Jewish life has been wiped from the collective Vilnius memory– it is instead replaced with a tale of brutal occupation, persecution, and forced compliance. Under this solemn narrative of memory, little room is left to remember the Jewish population mercilessly slaughtered during the Holocaust, making them a rare sort of historical gem hidden from the public view.

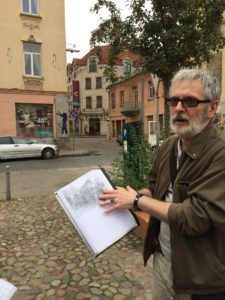

These gems are precious, and therefore difficult to find without some type of expert guiding your discovery. For our seminar this expert took the form of a Jewish historian named Ilja who took us on a walking tour of old Vilnius and exposed areas of importance to Jewish memory– areas we would not have known existed without him. He first took us to the location in the heart of what was once the former Vilnius ghetto. One can almost feel the weight of the forty thousand or so souls that were once forced to live in the cramped quarters. Yet, there is no monument, statue, or plaque at the location to memorialize those who were lost. Instead, there is only a faint Star of David that was defiantly carved into the side of a building many years ago. The following day we were given another tour, this time by a young woman named Martyna. Martyna is an official certified tour guide of the city of Vilnius, having received training on what information to provide to guests and under which guidelines to answer questions. Unlike Ilja, Martyna provided little to no mention of any Jewish memory or influence in the city and spoke in a patriotic tone, putting the national narrative of Lithuania as a courageous country who has vigorously fought for their independence. The dichotomy between the narratives of these two tours opened my eyes to the ways in which various actors can play a role in the evident manipulation of historical memory.

These gems are precious, and therefore difficult to find without some type of expert guiding your discovery. For our seminar this expert took the form of a Jewish historian named Ilja who took us on a walking tour of old Vilnius and exposed areas of importance to Jewish memory– areas we would not have known existed without him. He first took us to the location in the heart of what was once the former Vilnius ghetto. One can almost feel the weight of the forty thousand or so souls that were once forced to live in the cramped quarters. Yet, there is no monument, statue, or plaque at the location to memorialize those who were lost. Instead, there is only a faint Star of David that was defiantly carved into the side of a building many years ago. The following day we were given another tour, this time by a young woman named Martyna. Martyna is an official certified tour guide of the city of Vilnius, having received training on what information to provide to guests and under which guidelines to answer questions. Unlike Ilja, Martyna provided little to no mention of any Jewish memory or influence in the city and spoke in a patriotic tone, putting the national narrative of Lithuania as a courageous country who has vigorously fought for their independence. The dichotomy between the narratives of these two tours opened my eyes to the ways in which various actors can play a role in the evident manipulation of historical memory.

In Lithuania and other eastern European countries, the reconciliation of mass genocide during the twentieth century has begun only as recently as twenty years ago. The large gap left by the near complete decimation of an ethnic minority and subsequent Soviet occupation of these Eastern European countries has delayed attempts at reconciliation and remembrance, due to the strength of the iron curtain as well as a similar shield of patriotic nationalism. In Vilnius, the Jewish State Museum and the Museum of Genocide Victims attempt to shed layers away from this shield, to create a true narrative for the years lost during WWII as well as during Soviet occupation. The Jewish State Museum offers a clear history of Jewish life in Vilnius, showing the lives of the victims before and during the Holocaust– therefore providing an image of genocide as it truly occurred to those who suffered, and lost, the most. Adversely, the Museum of Genocide Victims provided a much broader and Lithuanian-nationalistic view of the same time period. Instead of making extensive mention of the Jewish population that was decimated by the twentieth century genocide, the museum primarily focused on the patriotic tragedy of the “Freedom Fighters” who were wrongly imprisoned and executed by Soviet forces following WWII. The construction of such a nationalistic museum comes as no surprise considering the country was under the administration of the USSR for over forty decades. A time during which Stalin deported thousands of Lithuanians to Serbia and assisted in erasing the genocide of the Jewish population by referring to them as cosmopolitans and marking them as “victims of fascism” (Cassedy, p. 78).

In Lithuania and other eastern European countries, the reconciliation of mass genocide during the twentieth century has begun only as recently as twenty years ago. The large gap left by the near complete decimation of an ethnic minority and subsequent Soviet occupation of these Eastern European countries has delayed attempts at reconciliation and remembrance, due to the strength of the iron curtain as well as a similar shield of patriotic nationalism. In Vilnius, the Jewish State Museum and the Museum of Genocide Victims attempt to shed layers away from this shield, to create a true narrative for the years lost during WWII as well as during Soviet occupation. The Jewish State Museum offers a clear history of Jewish life in Vilnius, showing the lives of the victims before and during the Holocaust– therefore providing an image of genocide as it truly occurred to those who suffered, and lost, the most. Adversely, the Museum of Genocide Victims provided a much broader and Lithuanian-nationalistic view of the same time period. Instead of making extensive mention of the Jewish population that was decimated by the twentieth century genocide, the museum primarily focused on the patriotic tragedy of the “Freedom Fighters” who were wrongly imprisoned and executed by Soviet forces following WWII. The construction of such a nationalistic museum comes as no surprise considering the country was under the administration of the USSR for over forty decades. A time during which Stalin deported thousands of Lithuanians to Serbia and assisted in erasing the genocide of the Jewish population by referring to them as cosmopolitans and marking them as “victims of fascism” (Cassedy, p. 78).

A tourist visiting the city without the guidance of someone like Ilja would likely leave the city with no memory of the tremendous amount of Jewish lives lost, but rather with a vision of patriotic fighters under communist suppression, vigorously fighting for their freedom. In order to understand how society has moved forward in the wake of such tragedy, it is imperative to recognize the role of civil associations in shaping a vision of the past. Establishing collective is accurately portrayed and available to the public is often ensured by civil associations– educational centers, museums, etc.– and it is through popularity and pressure by these associations that political and societal change is enacted (Kumar, p. 6). The variations in these museums’ use of rhetoric and portrayals of historical fact reflect an internal struggle over the control over the national narrative. They indicate a desire to manipulate the nation’s identity around the absolute positive legacy of the patriotic fighters who suffered under oppressive foreign occupation. By manipulating memory into defined sources of absolute good and absolute bad we lose insight to the middle ground between the two, and fail to acknowledge the more complex reality where many Lithuanian people collaborated with Nazi forces in exterminating thousands of innocent Jewish families. In order for the country to move forward and do right by their wrongs, the various institutions within the country need to acknowledge the dark side of their history as well as the light. To the convenience of those willing to erase and manipulate memory by providing no distinction for the lost Jewish population, not many remain to speak up for themselves.

Of course, the topic of genocide is not pleasant and most people would prefer not to discuss it, to forget it and move on completely–but this is not how memory works. No matter how hard you try to forget, you never can. Standing next to the old library in the former Jewish ghetto, the true tragedy of the city’s past finally struck me. It came even harder when Ilja and the Jewish State Museum told the story of how during the time of the Ghetto, Jewish families sought to ensure education for their children still while virtually imprisoned. Without some sort of public memorial or open dialogue about the liquidation of the ghetto on September 23, 1943, the empty space that remains feels hollow. It is a forgotten shell of a place where so many were treated inhumanely and forced to reside. How could a city like Vilnius, so lively and rich in culture, not acknowledge the perseverance of their lost population? How could they not memorialize accounts of families trying to live normal lives while faced with a hopeless future?

Of course, the topic of genocide is not pleasant and most people would prefer not to discuss it, to forget it and move on completely–but this is not how memory works. No matter how hard you try to forget, you never can. Standing next to the old library in the former Jewish ghetto, the true tragedy of the city’s past finally struck me. It came even harder when Ilja and the Jewish State Museum told the story of how during the time of the Ghetto, Jewish families sought to ensure education for their children still while virtually imprisoned. Without some sort of public memorial or open dialogue about the liquidation of the ghetto on September 23, 1943, the empty space that remains feels hollow. It is a forgotten shell of a place where so many were treated inhumanely and forced to reside. How could a city like Vilnius, so lively and rich in culture, not acknowledge the perseverance of their lost population? How could they not memorialize accounts of families trying to live normal lives while faced with a hopeless future?

No matter the true answer, you can still feel the weight of past bearing down on the shoulders of society when you encounter these spaces, and it is not until society faces the mirror that we can see this burden and finally take it off.

Resources:

Cassedy, E. (2007). We Are All Here: Facing History in Lithuania. Bridges, 12(2), 77-85.

Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40358188

Kumar, K. (1993). Civil Society: An Inquiry into the Usefulness of an Historical Term. The British

Journal of Sociology, 44(3), 375-395. doi:1. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/591808 doi:1