Self-Hating Jewess Writes Pro-Palestine Article for Urban Labs Central Europe

By Farrell Brenner

Three months ago, I stood ankle-deep in the Dead Sea, staring at the misty mountains of Palestine on the other side. Breathing the briny air, burning my lungs a bit. Next to me, my friend, whose grandpa is Palestinian, squinted. How close it was. How far.

“If things had worked out, I would be standing on the other side of this,” she said quietly, referring to a volunteer opportunity she gave up to study abroad in Jordan and Lebanon.

I thought about that for a minute, tasting the particles of salt that clung to my lips.

“If things had worked out…” I started, thinking about how the ways that both our ascendants had been uprooted and assimilated, making possible our eventual meeting on this bank.

“…If things had worked out, I wouldn’t be alive,” she finished for me, and chuckled.

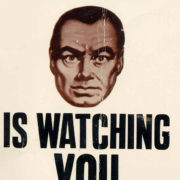

When Hannah Arendt published Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil on the misappropriation of the figure of the Nazi perpetrator in Holocaust remembrance, Trude Weiss Rosmarin wrote a review entitled “Self-Hating Jewess Writes Pro-Eichmann Series for the New Yorker.” I’m no Hannah Arendt, let’s be clear. But I smirk a bit reading this headline, thinking about the ways that my opposition to Israeli settler colonialism and solidarity with Palestinians have thrown into question my belonging in Jewish communities. Somehow, it is a reflection of my love (or lack thereof) of myself, my Jewishness.

What has Palestine to do with Holocaust remembrance in Central and Eastern Europe? Quite a bit. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu hit that nail on the head last week when he claimed that the Grand Mufti of Palestine gave Adolf Hitler the idea to exterminate the Jewish people. Not only is this historically untrue—the Final Solution was conceived long before the Mufti met Hitler—it also is a despicable manipulation of memory in order to extend the subordination of Palestinian people, recently heralded by expanded settlement and an uptick in violence, contrary to the goals of the Oslo Accords. And I just can’t roll with that.

What I found incredible among this fallacious nonsense was the response of the German government, which publically claimed responsibility for the Holocaust in order to negate Netanyahu’s dangerous gaffe. Of course, visiting Berlin a few days later and witnessing the general inadequacy of memorials to Jews, Roma and Sinti, homosexuals, and people with disabilities, it’s not possible to say that Germany has fully come to terms with its culpability in the destruction of these communities.

This is why the work of spaces like the Topographie des Terrors museum in Berlin are so crucial. This indoor and outdoor exhibition and art space brings to the forefront Arendt’s idea of a banal evil by comprehending the Holocaust through images and experiences of its perpetrators. What we can learn from this careful curation is that passivity and participation in Nazi crimes were quite normal, everyday occurrences. This lesson was amplified by the Places of Remembrance memorial in the Bavarian Quarter of Berlin; very simple signs pepper the neighborhood, with text on one side and an image of a related object on the other side. Their texts recreate the Nazi laws that slowly stripped Jews of their rights—Jews may not own radios (radio), Jews may only buy food between 4pm and 5pm (loaf of bread), et cetera. These laws began in the early 30’s, and the district where the signs are today was steadily ghettoized, and its Jews deported to camps. The memorial has upset many passersby and residents, and I can guess why: it completely disrupts the way that we have come to think about remembrance, as a listing of names, a solemn procession, a walk through a poor facsimile of what the victims might have experienced, a platitude of never again. Instead, the Places of Remembrance force us to confront the structural normality and legality of genocide. It is on the street, by the bus stop, out your window, over the playground where children are playing. Perhaps this tension indicates to us that there is some guilt here, and the horrifying acknowledgment of comfort: that life went on and goes on (literally) under these laws.

This sentiment is echoed when my Jewish peers cannot comprehend the Holocaust and Palestinian dispossession in the same breath. But I would like to think that humans are complex enough creatures to experience great oppression all the while standing on another’s throat. There is a large body of literature on how the Holocaust has been folded into the Israeli national narrative, and I cannot address it in any significant way here. What is important to note—and caution against—is the compulsion to say that the victims of the Holocaust and their descendants have become the perpetrators of the very crimes committed against them. Not only does this kind of statement discursively negate Holocaust victim status through what Michael Rothberg calls a “logic of equation,” but it also completely misunderstands the different kinds of violences enacted in these two different historical and geopolitical contexts (as Edward Said states in so many words, extermination and dispossession are not equitable). In an analysis of misleading photo essays that equate Warsaw Ghetto residents and Gazans, Rothberg also points to vast contextual differences surrounding the photos that disappear in their adjacency. At the same time, Rothberg astutely observes that “The situation in Gaza is the result of forms of Israeli control not even feasible during the Nazi genocide…” and that this entire discourse maintains the primacy of the Holocaust as the standard for genocidal violence and the concentration camp as the paradigm for the crisis of modernity and definition of human life.

(*takes deep breath*)

I realize now that this post has jumped around a bit, touching different pressure points of conflict and pain on a strange map. But I hope it is, to be Rotherbergian, multidirectional. Palestine and Warsaw are not the same—but they have much to do with each other, and it is through the nuanced discourses of remembrance emerging in particular innovative spaces in Berlin that I was able to grasp this complexity as a tangible, material reality. Centering perpetration and complicating victimhood are two tactics for reimagining history and creating sites for solidarity. How better to love myself, to love being Jewish, than to honor these memories as fully as possible—in all their contradictions—in order to expose and interrupt violence, rather than as limited, glorified ideals that undergird violence.