Auschwitz: The Challenge of Remembering

By Arielle Pressman

Today, the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp serves as a museum managed by the Polish state, more specifically the Ministry of Culture. Even though, the site receives approximately 1.6 million visitors a year, it still faces challenges on how to preserve the memory and serve as a respectful place of remembrance. Since the 1980’s, Auschwitz-Birkenau as a museum has evolved significantly reflecting not only Poland’s own struggle to come to terms with its past, but also as a part of the reconciliation process between Poles and Jews.

Since the Second World War, Auschwitz has epitomized of the evils that took place during the Holocaust. Even though there is actually more to the Holocaust than Auschwitz, many define the evils of Auschwitz as encompassing the evils of the Holocaust in their entirety. For Poland, the site of the majority of the Nazi concentration camps and a large number of the mass murder sites, dealing with the past takes on an additional very personal dimension. According to Pam R. Jenoff’s article titled “Managing Memory: The Legal Status of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Resolution of Conflicts in the Post-Communist Era,” Auschwitz presents itself as a national struggle for Poland. While this struggle began during the communist period, especially the coming to terms with the fact a once prominent and flourishing Jewish community had been destroyed and forgotten, after 1989 a new chapter of dealing with the past and many of the problems areas of Polish-Jewish relations and reconciliation began. “The many issues surrounding the former concentration camp site today reflect the struggles of a nation attempting to orient itself as a modern, democratic state.”[i] However, quite a bit of progress has been made since the fall of Communism in preserving the memory of the history of the Holocaust and the Second World War is retold.

One of the few surviving gas chambers. Also has a cremitorium to burn the bodies, hiding the evidence.

In his book Poland and the Jews: Reflections of a Polish Polish Jew, Stanislaw Krajewski discusses the today’s challenge in preserving the memory at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Since the end of the war, when Auschwitz became a museum, there have been many challenges and controversies surrounding the way the past is dealt with at the museum. One of those challenges, as Stanislaw Krajewski mentions in his essay “Auschwitz as a Challenge” was about “misleading comparisons” as to the fates of inmates at Auschwitz.[ii] Another challenge was the lack of acknowledgement that Jewish victims were the dominant victims, which conceals the notion that the Holocaust was the anti-Semitic attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe. “For decades, the fact that the overwhelming majority of camp victims were Jews, who perished only because of their origin, was ignored […] Descriptions [in the museum, guidebooks and school textbooks] totally disregarded the fact that most and sometimes all the victims from various countries were Jewish. As an example, Krajewski mentions how a new memorial placed on the grounds of Birkenau in 1967 referred to only victims of fascism, but made no mention of Jewish persecution or anti-Semitism or even that the majority of victims of the camp were Jewish. “The memorial made no mention of the Jews and did not contain a single Jewish motif! Recalling the victims, it kept them totally anonymous…It is easy to speak about millions of victims, but it is difficult to imagine them. Only in the 1980’s did the museum change its approach to represent the victims. The words visitors see today make it clear that Jews were the dominant victim of the camp. The text of the Monument reads: “Forever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity, where the Nazis murdered one and a half million men, women, and children, mainly Jews from various countries of Europe…Auschwitz-Birkenau 1940-1945.”

Entrance to the new exhibit at Auschwitz dedicated to Jewish victim. The Hebrew letters say the word, Shoah

Today, the museum at Auschwitz Birkenau prominently displays and differentiates between the victims of the Holocaust and the camp itself. If there is no name or face to the victim, then how would one relate to their suffering? By exposing the history of Jewish persecution, visitors are able to learn more about the fate of the Jewish people of Europe. Unlike communist Poland, the memory of the Jews is no longer erased. Poles, along with other visitors from around the world, can develop a new understanding of the victims – especially the Jewish victims –who suffered and died at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

An important new exhibit that recently opened at Auschwitz is called “SHOAH,” located in Block 27. This exhibit takes a step further in the way the victims of Auschwitz and the Holocaust are remembered. It was prepared mainly by Yad Vashem, the Israeli institution that deals with Holocaust commemoration, but in cooperation with the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. After Israeli Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon visited the site in 2005, the Israeli government decided to fund a new exhibit dedicated to victims of the attempt to exterminate all the Jews of Europe. When creating the exhibit, Yad Vashem dealt with the challenges related to both the contents of the exhibit and its design. Overall, the goal of Yad Vashem was to present to the world the definition of the Shoah, which was the attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe, by allowing the visitors to relate to the suffering endured. In an early part of the exhibit, the visitors enter a room where on multiple screens we see pre-war videos of Jewish life around the world. By showing videos of laughing children playing together and families sitting down for dinner, visitors can feel more connected with the victims as we see these individuals and communities living their everyday lives before the war. Followed by videos of the Nazi policies implemented and a room of artwork by some of the children murdered, the visitors are able to see the victims as humans. What we see is suffering and a connection that one does not have to be Jewish, or have any ties to the Holocaust to have.

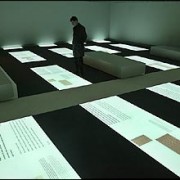

Arguably, the most important part of the exhibit is the final room, which contains a list of victims whose names are known. Since 1955, Yad Vashem has strived to find a name for every one of the six million victims. By giving the victims a name, they become a human being who suffered. The installation, titled “Book of Names,” consists of lists of names printed in alphabetic order on large double-sided sheets of papers. The book is the only thing in the room, forcing visitors to focus attention on the victims themselves. Visitors can open the Book and search for individual names. While about 4.2 million names have been discovered, there will be names forever unknown.[iii]

It is positive thing that the memory of the Jewish victims is becoming more visible. However, preserving the memory is a never-ending task that will depend on many actors. The site must do what it can to attract visitors and the visitors must be able to connect with the suffering of the victims.

[i]Pam R. Jenoff, Managing Memory: The Legal Status Of Auschwitz-Birkenau And Resolution Of Conflicts In The Post-Communist Era, The Polish Review, Vol. 46, No. 2 (2001), 132

[ii]Stanislaw Krajewski, Poland and the Jews: Reflections of a Polish Polish Jew, (Krakow: Austeria, 2005), 33-34.