The New Jewish Cemetery in Wroclaw

Wroclaw’s New Jewish Cemetery was founded in 1902 when Wroclaw’s Old Jewish Cemetery which, due to its central location near the center of Wroclaw, had no more room for expansion. The New Jewish Cemetery occupies roughly 27 acres, although most of the cemetery is closed off due to safety concerns and ongoing restoration projects. The majority of the cemetery’s occupants are German Jews from before World War II, while near the front of the cemetery Jewish Poles are buried. Between the year 1933 and all the way to 1968, the Jews of German Breslau and Polish Wroclaw were constantly being persecuted and systematically murdered or resettled either by the Nazis or by the anti-Jewish sentiments within communist Poland. By 1968, there was effectively no Jewish population to be spoken of within Wroclaw. The state of the cemetery today is a chilling reminder of what the Jewish community had once been before these decades of persecution, its vastness contrasting with its lack of visitors causing one to reflect on what had once been a thriving Jewish community, and how such a community could have been reduced to virtually nothing.

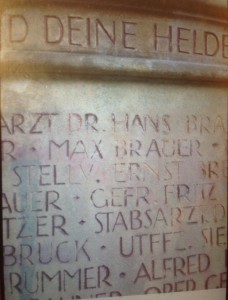

As a tangible place of memory for the Jewish presence in Wroclaw, the actual aesthetic of the cemetery was quite unsettling. The barbed wire which surrounded the perimeter served as a preliminary indicator of what was to come. The entirety of the cemetery rebounded a feeling of neglect that somewhat over powered a sense of reverence. The broken headstones and the marked memorial was not just sign of natural decay. One of the students visiting the cemetery actually found his name- Max Brauer- amongst the names inscribed on the monument for fallen German Jews of WWI. Immediately upon seeing his name, he created an instant bond with the site. The moment however was marred by a smear of red spray paint; a swastika had been emblazoned over the monument, tainting the memory of this hallowed place and symbolizing the continued rift between the Jewish community and the Polish population of Wroclaw, and indeed all of Poland. Compared to the Polish cemetery, which is predominately Catholic, there is no better word to describe the Jewish cemetery other than unloved. It is evident that only a few people pay their respects by putting a candle, flowers, or stones on the graves. On the other hand, the predominately Polish Catholic cemeteries in the city are flourishing; flowers, candles and decorations surround the grounds, not to mention the vast number of people that can be seen at any given day within the cemetery. The newer headstones of the Polish Jews within the New Jewish Cemetery, however, seem to have been relatively well watched over in comparison to previous years when vandalism and disrepair were the norm. Although few in number, the headstones of these recently interred Polish Jews have the same aesthetic of candles and flowers that can be found in the Catholic cemeteries.

Most of the people tied to this hallowed place have been displaced, murdered, or have moved away due to the decades of persecution under both the Nazi and post-war communist regimes. Those who are left find little personal connection to this site of memory and thus put little effort into preserving or protecting the area beyond that of their own loved ones’ graves. This responsibility has been taken up by those who understand the importance of this site as a marker of historical Jewish presence in this seemingly non-Jewish area. These people, such as Piotr Gotowicki whom we met during our visit and who is the groundskeeper, have dedicated their time to honoring those who are buried there and those who are remembered in the memorial to Jewish German soldiers of World War I. Despite the lack of support on the part of the local community, the cemetery is continuing to serve as a reminder that it truly only takes a few dedicated people to continue a legacy of memory. This site represents one of the last few holds of Jewish memory from before the Holocaust, and it seems its importance is beginning to be recognized.

by Max Brauer, Abbey Gordon, Tiffany Lyons