Reformers, Protesters, and Dissidents in a Communist Czechoslovakia

By Alexander Wilgocki

Depending on your age, it may be difficult to imagine a world where the Czech Republic and Slovakia were one nation. Today, two nations exist with their own flags, languages, currency in use (Slovakia uses the Euro while the Czech Rep. has the koruna), and beautiful cities and landscapes. However, when the two states were one, under rule by the nation’s Communist Party, Komunistická Strana Československa, they shared between them at times both a public and discreet resistance to their totalitarian government. During the Communist period of Czechoslovakia protesters and dissidents alike would resist and criticize the government oppression in whichever ways they believed would be most effective.

In the beginning of 1968 Alexander Dubček was elected as First Secretary of Czechoslovakia’s Communist Party. Almost immediately after he took his new office, Alexander Dubček made attempts to reform Czechoslovakia, both in terms of democratization and economic decentralization. An Action Program contained the right to assemble/association, free expression, free press, independent courts, and the freedom of travel. Dubček’s call for reforms as “socialism with a human face” naturally did not sit well with other socialist states and current leader of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev, who took Dubček’s words both as insulting their governments for being socialist without a human face and a clear and present threat to Soviet control over their satellite states. After attempts by the Brezhnev, and other leaders East of the Iron Curtain to stop or, at the very least, restrict the planned reforms, four countries within the Warsaw Pact – Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and the Soviet Union – sent armies to invade and occupy Czechoslovakia. Reactions to the invasion produced many forms of nonviolent resistance. According to anthropologist Krista Hegburg, who met with us at Charles University on September 26th, one unique example of Czech resistance was that citizens would try talking to Soviet soldiers and change their minds on what they were being ordered to do, actually convincing several soldiers to defect.

A starkly different example of resistance was by Jan Palach. On January 16, 1969, Palach set himself on fire (also know as “self-immolation”) as a form of political protest to the invasion. After painfully sacrificing his own life to criticize the actions of the Soviet Union and individuals supporting them, he is memorialized in several locations within Prague. Commemorating what he had suffered, the open area in front of Charles University within the old town was renamed from the Square of Red Army Soldiers in 1948 to Jan Palach Square forty-one years later. A subtler tribute to Jan Palach, and one that I had the privilege of visiting during my exploration of Prague rests in front of the National Museum in Wenceslas Square. There on the sidewalk, lays a small memorial to Jan Palach erected after the Communist regime fell.

Unlike the renaming of the square, this includes a small, but physical, cross partially submerged into the sidewalk memorializing the tragic end of Jan Palach’s life. Stumbling upon this on my way to another part of the city, it was only after I had returned to my hotel and told a friend about it that I realized what it was a tribute to. Making this realization, the memorial began to leave a greater impression on me than it initially had. The brutality of Jan Palach’s choice for how he would protest, combined with the simplicity and location of the modest tribute to his actions, made me re-consider how his actions should be remembered and in what form. Would a grandiose statue of him depict the inner-strength it required sacrificing one’s life better? Does a smaller memorial diminish that same inner-strength? Regardless of what I thought, I knew that I was not the only person that day who could have walked by the memorial, never knowing about the man it was created for nor the severe length he had gone to express his harsh disapproval of a totalitarian regime’s actions.

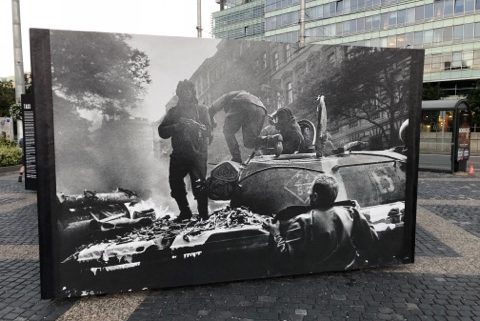

One of the enlarged pictures of the Prague Spring in front of the Presidential (Bratislava, Slovakia)

While there were many among Jan Palach in Prague who resisted the occupation of foreign armies, plenty more across the nation of, what was then, Czechoslovakia protested the actions of the Soviet Union and collaborating countries from the Warsaw Pact. And even as the two nations govern their separate territories and citizens today, the past is not forgotten. Right in front of the Presidential Palace in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, were walls over 6 feet high with blown-up pictures of the resistance happening in Prague and Bratislava alike. Some showed the tanks rolling through crowded streets with little physical resistance by the Czech citizens who filled up any remaining space. One in particular showed one man displaying pure defiance, baring his chest out in front of a Soviet tank in the middle of an open crossroads. Images such as these made me immediately call to mind those that may be slightly more famous, such as “tank man” who stood in front of a line of Chinese tanks during the Tiananmen Square protests. But seeing these unique photographs for the first time evoked an impression of an unbreakable solidarity that existed between the people of Czechoslovakia then in a time of resistance and even to this day across borders that were erected twenty-five years ago.

Alongside these moments of overt resistance to undisguised occupation and oppression, others resisted not by public protest but by covert actions that would subvert the ideological, intellectual, and cultural stranglehold maintained by the totalitarian leaders in power. Tucked away within an average and unelaborate building complex is the Libri Prohibiti. This organization in an independent and non-profit library, containing over thousands of prohibited literature during the Communist regime. Many works are what would be considered by the ruling government at that time as critical of communism the current political and economy systems in place. Some were copies of documents such as Charter 77, a request by Czechoslovakian writers and intellectuals calling for the recognition of several basic human rights. Other works, surprisingly, were fictional stories like Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Visiting this organization and simply observing the thousands of books and works filling an entire wall of bookshelves was astonishing. My classmates and I learned about the different ways they would increase their productivity and methods to making these materials easier to conceal. We flipped through pages of carbon paper, much thinner than regular paper and allowing 15 copies than usual to be made at once. I squinted my eyes attempting to read a book no larger than the palm of my hand, only to be handed a bar of magnifying glass that would enlarge lines of text to sizes I could comfortably read. My own personal grievances with censorship helped me form a greater appreciation for the organization that preserved efforts of cunning resistance by dissidents of a nation requiring intellectual and ideological conformity.

These were just a few examples of how people across Czechoslovakia would not submit to the chains of authoritarian government and the restrictions to individual freedom and democracy that they demanded. The techniques and methods employed vary case by case, but what ties them all together is their unity in working against regulations of the human mind and spirit.