Hammer and Sickle; Canvas and Brush

By Abbey Metzler

Let me tell you a story.

The year is 1963. You live in a town up in the hills outside of Budapest. Your country, the Hungarian People’s Republic, is run by the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. Or really it is run by men in Moscow who have never been to your town, and you certainly will never visit theirs. But, none of that matters to you. You have your friends and your family and your job to be concerned with. The friends test your jealousy and your family tests your patience. And, your job tests your body. The ache in your back follows you to work in the morning and the ache in your calves follows you to bed. You feel a kinship with the statue you pass when you leave the city every evening. He is a giant, copper man. With his arm outstretched, banner in hand, he is caught mid forward stride. Purposeful leg to powerful fist, he is the sculpted embodiment of momentum. You don’t remember what he’s commemorating — was it our Soviet liberators? — but it doesn’t matter. You see your own perpetual march in his. His determined face is a reminder that you want to keep moving too. If you keep soldering the machine parts, and feeding your family, and following your role then you too can be twenty feet tall.

Every people has its origin myth. The origin myth can be a literal telling of how your society started: a revolution, a catastrophe, the arrival of a prophet. But, it always determines the shape of the society. What will the people fight for? What do the people value? What will the people protect? These answers are upheld by the dominant ideology of the society and are fiercely defended. The government usually is going to represent that dominant ideology. In Hungary, in 1963, that ideology was communism. Hungary, after World War II, was made a part of the Soviet Bloc. The country was swallowed by communism, and the origin myth shifted to reflect that. The people would fight for a workers’ state. The people value collectivism. The people will protect their way of life from capitalists.

A government always wants its people to believe its story. And, a totalitarian state relies on its people believing its story. To fully convince Hungary’s citizens of this new myth, the government permeated daily life with evidence that the story was the truth. That is where public art entered the scene. Art is an effective storyteller because it speaks a universal tongue. Whether you realize it or not, it is nudging you towards believing whatever story it was created to narrate. This subliminal power of convincing is why art is so useful in politics. Socialist Realism was a style conceived with the desire to aestheticize communist ideology. By turning this ideology into something visually appealing, the ideology became easier to dispense to the masses.

One of the many carved stone friezes. The two people are rendered with strong, straight-lined bodies. And, the gun in the man’s hand represents achieved Soviet masculinity through militarism.

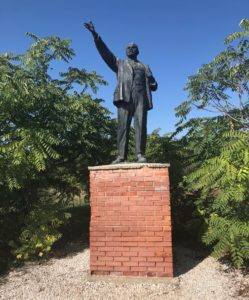

Looking at the Socialist Realism statues that once stood in Soviet Era Budapest, in their now home of Memento Park, you can see the origin myth of communist Hungary written on their every surface. The people are strong. The curves of the body are smoothed to resolute lines, all for the value of a strong backbone. The leaders get their own pedestals. Lenin’s stately bearing assures the masses that this man is powerful, and worth listening to, but doesn’t stray into bourgeoisie gravitas. In fact, this art is decidedly non-bourgeoisie. There are no frivolous flourishes. The

A monument to Lenin. The statue towers over the average person, so any passersby always has to gaze up at his glory.

designs are geometric and striking. They reflect power more than finesse. The rationality of such designs suits a people who supposedly have rejected excess and embraced hard work. In the stone work of these statues there is a call back to humankind’s most ancient art. The frieze style and exaggerated stone textures recall the stuff that our ancestors carved or painted onto the walls of the caves they called home. Our prehistoric selves used the resources they had at hand. They lived and worked in communities dedicated to staying alive in a hostile world. It reasons that communist aesthetics would harken back to a time that they perceive as sharing their values.

A large stone monument, depicting a line of soldiers in full charge. This piece perfectly reflects the style of rough stone texture, which recalls ancient art carvings.

In the course of my studies, it feels like there is a wall between me and life as it was in communist countries. As an American who grew up hearing really only my country’s origin myth, one that proclaims us a once underdog rebels and now the protectors of the Free World, I have to consciously shed my warped understanding of every “other”. My family never lived under communism. My textbooks focus on the big players in history, the ones who were winning battles or signing economic plans. People like myself rarely make the pages of these academic texts, so I’ve never been able to place myself fully into the history I read about. But, standing in Memento Park after having driven out of Budapest, I felt like I found a window in. That window was the Socialist Realism art. I could imagine how walking past a stone carved wall with a line of faceless soldiers charging forward with their guns would impact me if it was all I ever saw. This theme of militarism, repeated with only the smallest alterations, would have slanted my worldview. I think it’s easy to see outdated propaganda for what it is. Even propaganda of our time is transparent if you’re looking for it. But, art seems to get overlooked as a political medium. The analysis of this art era’s symbolic meaning may seem trivial. It may even seem like a stretch to apply ideology on how a sculpture is carved. But, ideology and art are both most effective at their jobs of convincing when you don’t realize you are being convinced. If we can recognize Gothic art style as a product of a society so fearful of Hell that the eye needed to be continuously drawn up towards the heavens, then we can recognize Socialist Realism as a product, and a driving force, of communist values.