Who Are Memorials For?

By Jay Skelton

As our group traveled around Europe, the most common type of place we visited was a memorial of some kind or another. Most of those we saw were for the victims of Nazi genocide and the Holocaust, although some were dedicated to soldiers and those who fought and died for their country or what they believed in. These memorials about soldiers and victims are almost always controversial and spark the most intense conversations within in the group. One question that never seems to come up is who the memorials are for. On the surface it seems simple, the monuments are to memorialize the victims of a tragedy. But that is only surface level, and begs the following question:

Stepping Stones – simple memorials in Berlin marking the houses where Jewish Holocaust victims lived before deportation, forcing people to confront the reality of the Holocaust as they move through the city.

Are memorials for the victims? Victims whose life was taken from them because of some evil they could not expect. Victims who were murdered because some other person or people never wanted them to exist in the first place. Victims who were taken from their families and their friends, never to be seen again. Victims whose only lingering presence is in their absence, the gaping whole in society left by what they could have done. A memorial cannot fill that void. Those people can never visit a site made of stone, or see again the place they were murdered, where their bodies were burned or buried. They cannot visit and mourn at the sites we created for them. And, when these sites are pure creations, separate from the historical places where tragedies occur they can become open to interpretation. Even worse, when added on top of historical places, they become superfluous, and can even overwrite the power that the site holds. These types of memorials remove themselves from the actual suffering of the victims and cannot truly honor victims or survivors.

The survivors lost everything but their lives, to emerge at the end of an immense tragedy,

The Shoes on The Danube memorial in Budapest, marks a spot where thousands of Jews were shot into the Danube river. This site is perhaps controversial for lacking descriptors, but it forces people to think about what had happened.

beaten, broken and scarred. Their lives contained unimaginable pain and anguish, having seen their friends and families murdered knowing at any time they could be next. The survivors will never forget what they endured or the people that endured it with them. If they cannot forget the tragedies that befell them, why do we build a place, a building, or a sculpture for them to remember the one thing they will never forget? Can a memorial even capture a brief part of their experience, or make the audience understand in even a small way what they went through?

If memorials are not for the people who are being memorialized, then there is only one other option. They are for everyone else. They are for us. The people that visit them, that mourn at them, and remember loved ones lost, or tragedies in our past. But what if those people cannot mourn for loved ones they lost, because they have no direct connection to the events that have been permanently set in stone? Those people who never knew a future victim, met a survivor, or even faced extreme persecution in their life. In fact, those are the people that are the most important – the memorial has the possibility to build the connection within the hearts of those people who have none. Memorials can connect us to events and people where no other connection could exist. And that connection has incredible power. In fact, it can be life-saving.

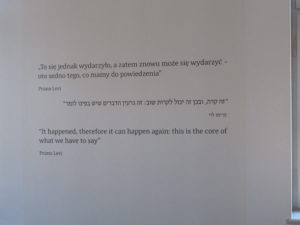

When people have a connection to an event, they are more likely to learn more about it. When it comes to something like the Holocaust, which was a governmentally run genocide, knowing more about it can allow people to see a connection between the past and the present. In essence, they might be able to discern when certain people or policies can lead down a dark path. And some of the people who see that connection might just have the courage to stand up and fight against dangerous policies; and, in that way, they could save lives. Therefore, the purpose of a memorial is not to honor the dead, but to motivate the living to honor the dead. But not by simply remembering them, but by acting in a way that honors them. By protecting those who have no one else to protect them, and above all to remember one horrible truth: “It happened, therefore it can happen again.” This is the immense power that a memorial has. It does not simply remember the past, but it can affect the future through those who interact with it. That is how discussions regarding

memorials should be framed. By remembering that they are for us, so we can have the courage to change the future.