This History Is (Not) For You

By Aren Burnside

Monuments, memorials, and museums all attempt to convey history to their visitors. Yet what audience are these structures aimed at? To whom are these monuments, memorials, and museums meant to teach history? In an era of increasing globalization and international travel, it might be easy to say everyone. However, an important feature of these structures tells us otherwise: the language in which they are written. When entering a space of history and memory such as these monuments, memorials, and museums, the language seemingly tells us either: this history is for you, or, this history is not for you.

The House of Terror in Budapest is one such space where language makes the museum’s history more exclusive. Inside the museum, practically all of the exhibits are written solely in Hungarian. Other posters and, in one case, a large hierarchical tree of the socialist party, have no translations. Without the help of our guide, almost all of the museum’s history would have been inaccessible to our group of non-Hungarian speaking students. Many other visitors to the museum had audio devices that they listened to as they traveled through the museum. While these devices may have had some more options for translation, they seemed to have hardly sufficed; when our tour group would enter a new room, many of the other visitors in that room would take out the audio device headphones and listen to the English descriptions given by our guide. There were even instances where individuals or small groups would latch onto our tour group and follow us to listen to the tour guide. Further, I can present no pictures from the House of Terror because photos taking was prohibited. This becomes a barrier for language as well: even should a foreign visitor wish to translate something and understand the context, they are prohibited from taking pictures and translating later. In these ways, the House of Terror’s selective use of Hungarian became a barrier for learning history. For Hungarian visitors, reading the exhibits and learning the history presented was no problem. For foreign visitors who did not know Hungarian, the inaccessibility of the museum stood as a testament stating that this history was not for them. It was meant for the people of Hungary instead.

The House of Terror has been examined critically for its content, or lack thereof, as well. The museum has been criticized by many for a failure to successfully acknowledge the Jewish and Roma persons targeted during the Arrow Cross’ reign in Hungary and the building of a troubling narrative of Hungarian victimhood, in which Hungary was solely a victim, and not a perpetrator in the crimes of the Holocaust and socialist years (Szanto, 2003). In the museum, I think that these vacancies are rather apparent, especially to our group of international students. The penultimate room of the tour is a large room in the basement filled with large crosses, each adorned with a light. These are meant to signify the lives lost during German occupation and socialist rule. Hidden in the very back of these twenty some crosses is a single cross that bears the Star of David. One single cross to bear the lives of 600,000 Hungarian Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust. For myself, and for others in our group, this seemed hardly a sufficient commemoration of genocide. Then again, the history in this museum was not meant for us. Even though the House of Terror prides itself on being the most visited museum in Hungary, it is only written in Hungarian. It is meant for the Hungarian population and is visited by the Hungarian population. It is meant to reinforce this narrative that all of Hungary is a victim. It is meant to educate new generations: we were told that Hungarian secondary students are one of the largest demographics visiting the museum. This museum is not meant for us, a group of international students who grew up abroad, learning about the Holocaust through a different lens.

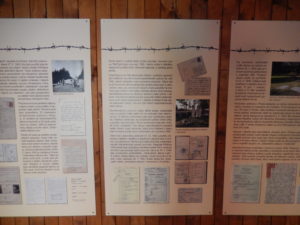

Another site where language played an interesting part in conveying history was Lety. Lety was a concentration camp in the Czech Republic that was labeled a “Gypsy camp”, as it was used to intern many Roma during German occupation. When visiting the Lety site, which is itself rather far out in the countryside, one will find a small building that details the history of the Lety camp. Inside this building, there are ten boards that give various descriptions of the Lety camp. The first of these is a board comprised entirely of English text that describes the history of the camp. On the other side of the door, there is a similar board written in German. This constitutes one wall of the building. The other three walls hold eight boards written in Czech and supplemented with photographs. Though I could not read them, these boards seemed to go into much greater detail, as they had a large amount of text and supporting photographs. For those visiting the Lety site, these boards are almost all of the information they will receive unless they travel to the site with someone with a greater knowledge of the site. This has a large impact for the interpretation of this site. The Lety site is open to many visitors, including foreign visitors, and accommodates them with the history written in two other languages. However, the greater depth and number of the Czech boards brands Lety as a domestic site. It’s history is meant mostly for those who live in the Czech Republic, the Roma whose families may have died there or were interned there, and the larger Roma community. Its goal is to be remembered by the people who surround the site most immediately, and while the site is happy to accommodate those wishing to learn the history, it still seemingly stands as a site for the Roma and the Czech people, rather than foreign visitors.

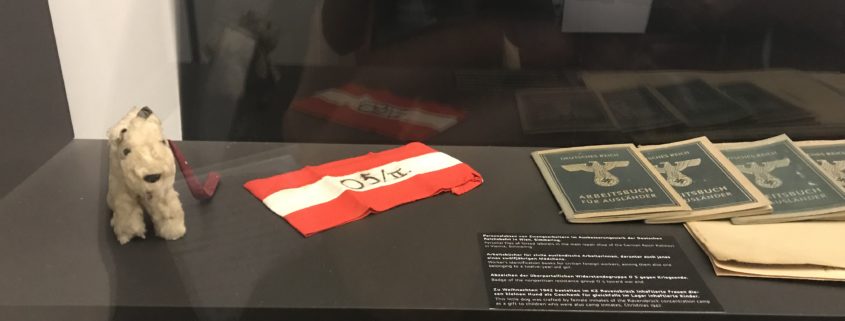

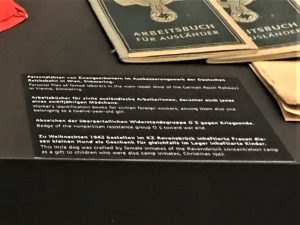

In Vienna we experienced an entirely different museum. Our group visited a small museum called the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance. This small, three room museum (though their total collection is quite extensive) attempts to display the history of resistance against nationalism socialism in Austria. Strangely enough for me, this small museum, that I probably would not have found on my own, had English translations for just about everything that was written in German. Anything and everything attempting to show history in the museum was presented in two languages in an attempt to assist the audience. The descriptions of Hitler’s rise to

power and violence against Jews: written in both German and English. The information about the artifacts presented: written in both German and English. It was all accessible. This history was for us. We were later told that the Documentation Center was founded by former resistance fighters to educate younger generations about resistance against nationalism socialism, should they ever encounter it. It was accessible to all because its goal was to reach all; though the history was of Austrian resistance fighters, this history was on display for everyone, so that anyone could resist against nationalism socialism. Here, this history is for everyone.

History is conveyed. Whether from one person to another, or through a text, or through other various means. Museum, memorials, and monuments attempt to convey their own histories, often with goals and audiences in mind. The language in which these buildings and monuments are written speaks to whom that history is meant for. In the House of Terror, the history being taught was meant for the Hungarians. At Lety, the history being taught was meant for the Roma and Czech, though it was accessible to far more. At the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance, the history being taught was meant for everyone. I often hear people say something along the lines of “history is written by the victors”. While this creates the question of who writes history, I think it is imperative that we must also ask: who is this history written for?