The Roma and Sinti Memorial

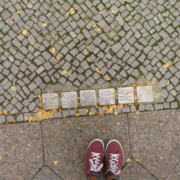

Tucked away, hidden, unimposing, quaint; these are words that have been used to describe the memorial to the murdered Roma and Sinti of Europe. It is a small memorial enclosed in the trees of the Tiergarten. It sits across the street from the Bundestag and a stone’s throw from the Brandenburg gate. One might think that this is prime real estate for a memorial. With many of the tourists of Berlin visiting those two iconic sites, there must also be plenty visiting the Roma and Sinti memorial. However, we were the only ones there. We were the only ones who stopped to take in the “quaint” memorial. Others came and went, took their souvenir pictures and were on their way to more exciting attractions.

The memorial was opened in 2012 by the German Government, although it was designed in the early 1990s by Israeli architect/designer Dani Karavan. The time delay in construction of the memorial reflects the hesitation by the German government to assume responsibility for the murder of about 500,000 Roma and Sinti people during the “Porajmos”, the Roma word for the Holocaust. The German government did not recognize the genocide until 1982. The persecution of the Roma by the Third Reich began in 1936 with the deportation of thousands of people to internment camps, followed by a transfer to concentration camps. In the camps, Roma prisoners were forced to wear an inverted brown triangle to distinguish them from other prisoners. The triangle in the center of the monument’s pond is symbolic of the triangle worn by the Roma. It is significant that beyond basic facts, little is known about the persecution of the Roma and their subsequent genocide during the years of 1936-1945.

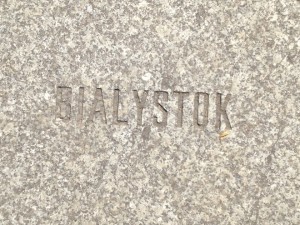

The significance of the memorial, in contrast to the memorials to the murdered Jews or the Homosexuals of Europe, is not found within the confines of the memories of those who visit or the history books. One of our students, Karolina, who is of Polish descent didn’t even know that Bialystok, the area in Poland where her family is from, that she has visited all her life, had a concentration camp which housed Roma. The Roma history is placed quietly on a wall of glass, which blocks off the memorial from the rest of the Tiergarten, as a signal that something important is here, hidden in the woods. In addition to the seemingly intentional obscurity, at the particular time of our visit the memorial also had to compete with the FIFA World Cup fan-zone. The beautiful melodies performed by the Sinti and Roma, which normally fill the silence that embodies those memorialized there, was completely overpowered by the bass and mixes of the new Germany. The website of the memorial even says that the memorial is open 24/7, but will be inaccessible to the public during the World Cup as a safety precaution to protect those in the fan-zone. Obviously this site is not a priority when competing with European Football.

We have often talked about frozen memories in our classes. Many people in our group voiced an opinion on the memorial as we walked away. Their idea was that the memorial to the Sinti and Roma murdered under National Socialism doesn’t lead to discussion on how to make the Roma situation better, but rather puts a metaphorical period to the conversation. While the German government gives money to programs, to the Roma people this site serves as the end of the conversation that something has to be done. These groups of people are still marginalized and are still considered pariahs in European society. According to our guide, the charter of this memorial site says there is a maximum capacity of two Roma allowed to beg in front of the memorial. After having been witness to many Roma, or “Gypsies”, being run out of public spaces in Wroclaw and in Berlin, it was a very sobering feeling to see that they are not even accepted at a memorial that is supposed to be for them.

By Lucas Galbier, Max Brauer, Tiffany Lyons, Karolina Wadolowska