The Lack of Discourse between Monuments and People

By: Kara McGrane

In most cases, a memorial is erected to commemorate an important event in history that a country would like to remember and to create a sense of pride in the country’s history. Such cannot be said for a majority of World War II memorials, in particular, many of the places of remembrance in Germany. These places remember a dark past: on e that people would like to hide but also remember so as to teach future generations of past mistakes. Yet, with this existing dichotomy, the memorials were built and stand even so. This conflict of ideas is in contrast to other places, cities, that do not seem to want to discuss the past, like Vilnius and Wrocław. In both cities there are places of forgotten or shoved-to-the-side memory, nothing like Berlin where the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is adjacent to the Brandenburg Gate, which is a symbol of the history of Europe and Germany during both turbulent and peaceful periods. The Gate’s role as a tourist attraction may help bolster the amount of visitors to the memorial but the memorial itself is also a tourist attraction, which is in stark contrast to that of Vilnius and Wrocław. These memorials to the past become sites of discussion, whether they would like to be or not, based upon their location, size, and topic. The discussion preserved by these three cities is either created, stifled, altered, or encouraged. How much discussion can be had if there seems to be over-acceptance or resistance to discuss the past?

To go not only in chronological order of visits but also, coincidentally, openness to discussion, I will start with Vilnius. This memorial, the Greenhouse Museum, does commemorate the past but its reluctance towards discourse is very particular. The Greenhouse remembers the Jewish past of Vilna in a factual and unadorned manner. The museum itself creates a discussion, but solely within its walls; the discussion does not reach past the doorframe. The museum may be state a state funded institution but it is not advertised as a place to go during a visitor’s stay in the city, like how the KGB museum in Vilnius is. It is up a back alleyway and only has a sign as large as a piece of A5 paper on a brick wall to mark where it is. The Greenhouse is filled to the brim with information but in such a way that everything fits within the walls of the immensely small building. Furthermore, the discussion of Jewish life in Vilnius is stifled because in order to examine Lithuanian Judaism during the Second World War, Lithuanians must be criminalized in history as a consequence of their participation in pogroms and other atrocities committed against the Jews. As a result, the Lithuanian involvement is deliberately omitted in all histories save the Greenhouse. Perhaps its size and location are effects of its topic thanks to the Lithuanian government. So, this discussion, or lack there of, has been stifled and altered in order to maintain the victimization of Lithuanians so as to not criminalize themselves.

In Wrocław, a discussion on the past was quickly created and just as quickly stifled. The history of Wrocław is tumultuous. It has been tossed between Polish and German hands and an invisible hand of the Soviet Union. At one point there was an era of degermanization which included effacing German inscriptions on buildings, rewriting that period of history, and razing German cemeteries so as to eradicate all markers of a German past. A German cemetery on the edge of the city was razed to create a blank space for the new Polish city and a blank page for the new Polish history. In 2008, the city erected the Monument to Shared Memory that remembers not just the razed German cemeteries but also all the other cemeteries that were destroyed in the polonization of Wrocław. This memorial takes a step forward by looking back and recognizing the past but that’s where the progress of conversation halts.

This memorial is located where the German cemetery was located which means it is located on the outskirts of the city, away from the tourist pathways. But not only is it just within the city limits but it is nestled deep into a park. The memorial is not fully visible to anyone who walks by the entrance as it is shrouded by towering trees. Also, the entrance is clearly marked with a sign stating the title of the monument but has nothing more to explain what it is, what it is for, why it was built. So unless a passerby had an immense curiosity for what “shared memory” is, but then also had knowledge of Polish or German so as to read the inscription on the monument, then they would know why the memorial exists. The memorial itself is quite large yet as a result of its location no one can see it unless he or she walks down a long passageway. There is a recent progress towards transparency, though inadvertent, as a new tram stop was built in front of the entrance of the monument. Same with Vilnius, the topic plays into perhaps the choice of the location. Wrocław’s German history is something that is hidden behind closed doors and is not something easily discussed on the street, which is why the discussion started by the Monument to shared memory was as quickly quieted.

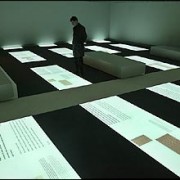

Finally, in Berlin, the close of our travels for this seminar acts as a culmination of an education of reconciliation. Berlin remembers its past, its transgressions, and its victims all throughout the city. With the myriad of monuments and memorials, Berlin itself acts like a history book. To use the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe as my main example is to use the memorial that would’ve been the biggest point of contention had it not been erected. The monument was first talked about and was in the beginning stages of planning in 1999. The entire memorial itself was finished and dedicated in 2005. In the beginning there was an arguments on whether or not erecting a monument would either generate or stem discussion and culpability of the past. In one of our readings, A Fence, citizens make statements on the memorial: “The discussion is the memorial,” “the memorial is already there,” the memorial is already here.” Perhaps Germany is the most open to remembering its past because its role as a transgressor is the most notorious, the most brutal, but also the best documented. The monument itself, in my opinion, does not stem the flow of discourse. I think its encourages the course of conversation by putting this brutal past out in the open and making it easier to speak about in daily life. Also, compared to Vilnius and Wrocław, Berlin knows its role as the transgressor so I don’t think that discussion of the past, present, and future can be closed once that large of a door has opened. The discussion is furthered even more by its location, size and topic. Like I noted before, The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is on a main street; next to the symbol of German history, the Brandenburg Gate; and two blocks away from the Reichstag. The dimension of the monument is massive: there are 2,711 stelae of varying heights and there is an underground place of information on the Jews in the Holocaust. If there weren’t straight lines of sight where a street was, a visitor could get lost within the columns. From the cupola of the Reichstag, the memorial is visible on a clear day. But as for the topic, the title of the monument is for the murdered Jews of Europe, not for the murdered Jews of the Holocaust. Why is the title so vague? Is the title vague because it creates an awkward, self-inhibiting conversation because it is assumed that the visitors know that the transgressor of these atrocities is Germany and the victims of brutality are Jews in the time period of the Holocaust, which the underground information center so clearly indicates while the above-ground monument leaves open for interpretation? The monument itself is a very touchy past to put out in the open of the capital of the land of the people who systematically murdered others. This monument creates and encourages conversation but the discourse to be had is self-inhibiting. Yet, out of all of these cities, even with its criticisms, Berlin is the most open to acceptance and questioning.

With these monuments, whichever way the information on the past is presented, an overall question can be asked: why should discussion need prompting when dealing with the topic at hand, genocide? All these monuments commemorate a past, whether to its full extent or not, but each monument seems to need a prompt in order to start a flow of conversation and its seems that whatever the prompt may be, whoever the prompt may be from seems to have some influence over the discussion created had by that particular monument. Why must these discussions have political or civil backing? As a collective memory, why can’t a country’s collective morals make a homogenous and sympathetic monument?