Erasing the Past: How Totalitarian Regimes Sought to Camouflage their Crimes

By Madison Bollart

When we think about totalitarianism, an immediate reaction often associates such a form of government with restriction, political repression, and complete control. In studying the 20th century particularly, we see this political system deem a particular prominence in Europe more times than one, specifically in Germany. To different extents, under the Third Reich and later in the German Democratic Republic, we see examples of totalitarian regimes carrying out persecution, surveillance, horrifying violations of human rights, and mass murder all while taking strategic caution in doing so to avoid international attention.

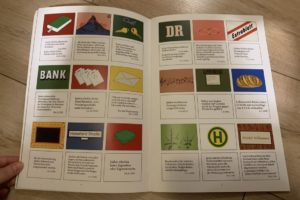

Street signs placed throughout Berlin’s Bavarian Quarter portrayed in the book Orte des Erinnerns, Places of Remembrance in Berlin by Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock

As early as Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933 came the first formal antisemitic legislation. Since the emancipation of Jews in the German Empire starting in the second half of the 19th century, Jews had made significant advances in German society. After Hitler’s rise to power, the position of Jews began to be fragile, with the implementation of numerous laws that would discriminate against, marginalize, and isolate Jews from society. During our time spent in Berlin, we discovered just how many rights were taken away from Jewish people while experiencing “Orte des Erinnerns” or Places of Remembrance, a memorial that documented the anti-Jewish laws that Nazi Germany implemented between 1933-1945. The memorial consists of 80 colorful signs, each which denotes a particular regulation aimed at restraining basic freedoms. The signs hanging from lamp posts are placed throughout the Bavarian Quarter of Berlin, an area which originally housed a large Jewish population.

As we walked around the neighborhood, looking for these signs dispersed throughout I could not help but feel uneasy as I realized just how many human rights were gradually confiscated from the Jewish community under the Nazi occupation. However, one sign in particular stood out to me apart from all of the others. It depicted the six Olympic rings on the front, and on the back read, “Antisemitic signs in Berlin are being temporarily removed for the 1936 Olympic Games.” This sign resonated with me for a number of reasons, but mainly because it illustrated the implementation of a policy which had a purpose of camouflaging the reality of the marginalization being carried out by Nazi Germany. The Olympics is an event which historically draws an incredible amount of international attention to whichever city it is hosted in. It is clear that Nazi Germany understood this, so it took preventative measures to evade international spotlight on the atrocities the regime carried out. This forced me to think that the Nazis must have known what they were doing was morally wrong from the very beginning if they had to take deliberate action to hide it from the rest of the world. This highlighted a great deal of irony to me; how a regime, which so openly flaunted its anti-Jewish agenda inside the country since coming to power through legislation, marches and mass rallies, simultaneously took such conscious efforts to cover it up during the international celebration of the Olympic games in 1936. “The Places of Rememberance” illustrates the gradual stripping of basic human rights of the Jewish population, crimes the Nazi regime sought to camoflage from the rest of the world.

I began to understand that the Nazis attempting to conceal their crimes was not isolated to 1936 Berlin, but was a recurring action which would take place even up until the final days of the regime’s power. By late 1944, it was becoming apparent to the Nazis that they were on the brink of being defeated by the Allies. In this realization, in November of 1944 head of the SS Heinrich Himmler ordered for the destruction of all of the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and deadliest of the Nazi concentration camps. The order was followed, and the gas chambers were dismantled and later blown up using dynamite. The Sondekommando, a group of mainly Jewish prisoners who were forced to clear the gas chambers and burn the bodies, were also forced to demolish the structures that were instrumental in killing their own people. Additionally, many SS officers burned documents and fled on the anticipation of defeat and exposure of their crimes. By the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau on January 27, 1945 the gas chambers had been destroyed, however evidence of wreckage of the gas chambers still remained, as well as storerooms of prisoners’ belongings which were stolen by the Nazis and planned to be brought to Germany. What remained would stand as a memory and reminder of terrible crimes against humanity and the mass genocide under the Third Reich.

My own visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau struck me with a wave of emotions; some anger but mostly sadness. I had learned the history and horrors of this place, and upon visiting it, I strangely hoped to find some clarity in understanding how a regime could systematically murder millions of people, and then later in a last-ditch effort, try and cover it all up. Our visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau allowed me to remember a history that the Nazi regime aimed to erase. I saw what remained of the gas chambers— the remnants of the instruments used for mass murder. While I did not find clarity, I did have the opportunity to see powerful pieces of the past— ones which sought to be eliminated.

The defeat of Nazi Germany proved to not be a culmination of totalitarian regimes covering up their crimes, but instead can be considered a precursor to a different regime’s suppression of its wrongdoings. Four years after the end of World War II came the formation of the German Democratic Republic or East Germany, a communist dictatorship and Soviet satellite state in the Eastern Bloc. Perhaps the most distinguishable characteristics of the regime were lack of freedom of expression, rule of law, and freedom of movement. This was enforced by the “Ministry for State Security” or the Stasi, the East German official state security service known for effectively instilling fear in civilians through excessive surveillance and espionage up until 1989. With the help and collaboration of unofficial informants, these secret police would ultimately invade every aspect of the personal lives of East Germans, reporting and obtaining even the most intimate details of the lives of neighbors, family, and friends. This network would accumulate millions of what would be referred to as the “Stasi Files.” Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Stasi officials began to quickly destroy the files, crucial components which serve as evidence of an incredibly invasive and repressive regime. In doing this, it is clear that the institution maintained a sort of obligation to avoid exposure under an international spotlight up until the very end of the regime. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, an institution was established which would allow citizens to view their files. Because many of these files were shredded or torn by the Stasi, efforts are ongoing by a special agency to piece together these documents to allow victims to view their files. However, due to lack of adequate technology, the agency has struggled to piece together these documents, and therefore has looked to a small group of individuals working to put the files back together by hand. Although tedious and difficult work, these efforts symbolize the ongoing efforts to put together and preserve a history that aimed to be destroyed and covered up by a totalitarian regime.

English translations of the regulations against Jews under the Nazi regime in Orte des Erinnerns, Places of Remembrance in Berlin by Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock

The backtracking measures taken by the Stasi act as another example of a 20th century regime attempting to erase their own iniquities. Totalitarian states making consious efforts to hide their crimes from the world demonstrates a powerful trait that we can associate with both the Nazi and Stasi regimes— an aim to erase history. In realizing this, I feel that we must take it as our responsibility to actively remember, something that these regimes deliberately intended to prevent. By diligently learning about those who were persecuted and the role of the perpetrators, we can preserve the past not only through physical memorials, but also through individual consciousness, memory, and understanding.