“Colossal Cement”

By: Madeline Diorio

Three months after walking around foreign cities, visiting museums, climbing towers and terraces, visiting monuments and museums and the most striking of all I find to be the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany. Driving through Berlin it seemed impossible that one would not be able to look out the window of the bus without being mesmerized by the sheer magnitude of the memorial that lies in the background. It was this site visit that I was most looking forward to visiting during our time in Berlin; however walking through it was nothing like I expected it to be.

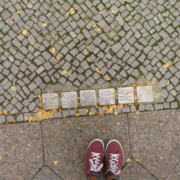

Prior to physically visiting the memorial the idea of what it would feel like walking into the site had never crossed my mind. It wasn’t something I thought about, the act of being on the outskirts and slowly walking in, which is how I had presumed visiting the memorial would be like. So it’s no wonder the shock I felt when we left the underground Museum to discover the exit led you up a stairwell right in the middle of the memorial. It was like being thrown in the middle of a maze and no one warned you how to get out. All of sudden without warning I was surrounded by colossal cement blocks and within seconds I had been separated from all of my peers I had just been with exiting the museum. I spun in circles an odd feeling as if I would be separated from everyone for the rest of the day as if there was no hope in finding them. Irit Dekel explains on page 83 of their piece Ways of Looking that in this memorial one must feel lost for it is a prevalent strategy of the memorial. As I walked hurriedly around the 2,711 blocks of all different sizes I found myself constantly running into other people until I turned a corner and almost collided with a classmate. I felt a rush of relief take over my body, I was not alone and I was not in a never ending maze. Together with two classmates we quietly and calmly walked down a row of grave-like structures up and over the uneven ground until we were outside of the memorial.

As I stood from the outside of the memorial looking into the middle where I had just come from I couldn’t help but think of how horrible it felt to feel as though I had unknowingly been thrown in the middle of the memorial with no preparations for what I was about to encounter. After catching my breath and taking a moment to look at the memorial as a whole I decided to delve back into the inner depths of this site. I had already known what it felt like to be seemingly dropped into the middle of this obstacle therefore I thought that starting from the outside and working my back to where I had been would be a much more pleasant experience where I could take time to reflect on everything we have learned over the course of this semester. If there is one thing I can say about this feeling of “preparedness” is that I was most definitely wrong.

Instead of feeling more at ease by starting from the outskirts and working my way in I felt an even stronger sense of despair than I had exiting the museum. As I slowly made my way deeper into the memorial I noticed that there was less light, the noise of the bustling city seemed to be somewhat suppressed and the towering blocks became increasingly more immense. I could not put together my feelings of unease and why I felt this way. What was it that made me so apprehensive about continuously moving further into this space of memorializing? Was it because I had yet to feel any type of unease at any other site, was it because here it was hard to reflect on what I had just learned because I felt so oppressed by these towering blocks? I knew I wouldn’t be able to answer these questions from within the memorial, so I took one last look around and began my walk back perimeter of this vast area.

As the day continued I still found it difficult to figure out where this sense of anxiety surrounding the stelae seemed to be coming from. It wasn’t until our class discussion that I realized why I had such a sense of unease. Several peers brought up this same feeling as they walked from the perimeter of the memorial into the middle. An assessment was made that possibly this is what it felt like to those who were victims of World War II. One moment you are walking similar ground as your friends and family, there is plenty of light and the next moment you are separated from everyone, lost in a maze, and seemingly consumed by a feeling of hopelessness. It was an astonishing realization when I heard my classmates describe their interpretations of the memorial because I it suddenly became clear that this is how I felt as I walked deeper into cement slabs. To me it was an indescribable feeling but through the words of my classmates and through the piece by Dekel I realized that this is the type of emotion that most people experience when visiting the memorial. Dekel poses the same question I felt on page 74 when she asks “is this like the Jews felt in the Holocaust? Does this symbolize the escalation of Nazi crimes and their scope?” before she mentions that these are the questions visitors pose to one another after their visits.

Others may wonder how one could compare walking around a memorial to what the victims could have possibly thought during WWII however I almost see a beauty in it even if I am interpreting the memorial incorrectly because as Dekel explains this is a place of reflection for all that could happen here. There is a beauty in the way the terrifying blocks tower over you and create this maze. That feeling of being alone but suddenly running into the people you had been with by turn a corner around a column. The is a beauty in being able to interpret such a vast memorial and to be able to try and find a deeper meaning than giant grave-like blocks of different sizes. It may have been a nerve racking experience, but when I had the time to reflect on what it truly meant to feel the way I did I found a beauty within those 2,711 cement slabs.