Rebuilding Berlin’s Identity

By Caroline Bartholomew

Berlin was founded in the thirteenth century, but you might never guess that from the way it looks today. Instead of walking along small, winding streets with half-timbered houses, you encounter a grid-like layout with modern buildings. I knew that Berlin had been almost completely destroyed by Allied bombing during World War II and yet I was still surprised to see such a modern metropolis.

According to an article from Der Spiegel, 80 percent of historic buildings in Germany’s main cities were destroyed during the war, and most buildings in Germany today were built after 1948. Millions of homeless residents and refugees posed a serious urban planning crisis for architects after the war — how do we rebuild Berlin? For the most part, they opted for more modern, hastily-built structures to accommodate all of the displaced people. In West Germany, money from the U.S. via the Marshall Plan helped build at least 5.3 million apartments in the first 15 years after the war.

These new buildings helped revitalize the city and bring it back to functionality, but one has to wonder whether or not Berlin’s identity suffered when the architects chose to modernize the city rather than rebuilding it according to its prewar plan. This also brings up the question of how the identity of a city is shaped — is it determined by the physical structures that already exist, or by the people that live there? In the case of Berlin, with so many people gone and moving around, the people themselves had to determine the character of their neighborhoods.

Seventy years after the war ended, neighborhoods in Berlin have built their distinct identities. For example, Charlottenberg is affluent and has more traditional architecture while areas like Prenzlauer Berg and Neukölln are up-and-coming and popular among young people. A neighborhood that really illustrates what it meant for Berlin to rebuild was Schöneberg, which was a modern neighborhood that had a large and well-assimilated population of Jews during the interwar period. After the war, because so many Jews who lived in this neighborhood never came back, the majority of inhabitants after the war were new. They had to establish themselves in a new neighborhood in order start the next chapter of their lives.

For many people, moving into a new building in a new neighborhood meant a blank slate and a chance to rebuild, even though it was not actually a blank slate. New apartments were built on top of the rubble without acknowledging the fate of past inhabitants. New residents of Schöneberg and others in places where Jews used to live went about their everyday lives, most likely with the knowledge of who had lived there before them but without any discussion. Directly after the war, citizens of West Germany did not openly discuss the war because “silence about the crimes of the Third Reich and German society was seen as necessary to establish a then fragile Western democracy,” writes Karen Till in her article, “A Fence.” It was not until the 1980s that the dialogue started to open up among West German citizens about remembrance. Till says that multiple monuments and museums were established to confront “the history of National Socialism through progressive educational centers, history workshop movements, neighborhood tours and more radical projects. This emerging decentralized form of social memory explicitly questioned the politics and legitimacy of national (centralized) places proposed by state and federal officials.”

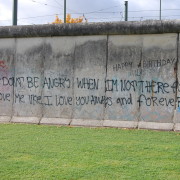

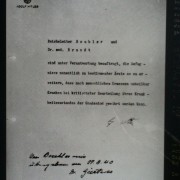

An example of a decentralized memorial we visited was the “Places of Remembrance” memorial by Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock in Schöneberg. These artists started their project in 1991 after the reunification of Germany and it was “one of the first major efforts to give permanent recognition to the ways the Holocaust reached into daily life in the German capital.” The memorial consists of small placards mounted on street signs and lampposts containing excerpts from the discriminatory laws against Jews imposed by the Nazi regime. Another decentralized monument is the “stumbling stones,” which mark sidewalks outside houses where Jews had once lived. Schöneberg’s sidewalks are covered with them, and they add real names and stories to the history of the neighborhood. I found these types of decentralized memorials to be more effective in some ways than the magnificent, national monuments we’ve seen because of how the signs of the monument fit in so seamlessly with the rest of the neighborhood. It serves as a reminder of the neighborhood’s past for the current inhabitants. The subtle nature of these monuments symbolizes how Jews were fully integrated into German society and discriminatory laws were passed gradually rather than dramatically all at once. Even though they were created almost 50 years after the Holocaust, integrating monuments like these into the fabric of a neighborhood is an important part of Berlin’s ongoing rebuilding and remembrance process.