The Linguistic Power of the Bavarian Quarter

By Charlotte Goodman

Jew (jü) Noun

1. a person belonging to a continuation through descent or conversion of the ancient Jewish people

Jew (joo) Adjective

2. Offensive. of Jews; Jewish.

“Citizens of German descent and Jews who enter marriages or extra-marital affairs with members of the other group will be imprisoned. As of today, mixed marriages are not valid.” – September 15, 1939

“To avoid giving foreign visitors a negative impression, signs with strong language will be removed. Signs such as ‘Jews are unwanted here’ will suffice.” – January 29, 1936

“Certain parts of Berlin are restricted for Jews.” – December 3, 1938

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

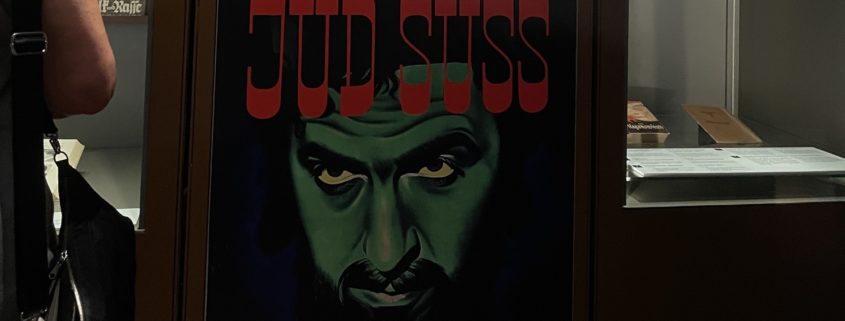

From the time of Hitler being appointed leader in 1933 until the end of the war in 1945, the word Jew developed a new negative connotation it hadn’t carried as strongly before. The word went from a simple word of identification, carrying no clear positive or negative connotation, to being an attack or an insult. The word was plastered onto antisemitic propaganda posters, placed upon the clothes of known Jews for forced identification, used in chants by the Nazi regime promoting Jewish death, and used to compare the Jewish people to vermin and pests. Before the Holocaust in the Bavarian Quarter though, Jews were a very integrated into local society. The Jews in the Bavarian quarter were not just Jews, they were Germans, and they were friends, neighbors and even family. Jews and Jewish families in the quarter were doctors, shop owners, politicians, teachers and more. Jews were a part of everyday life. Once the Holocaust started though, the word Jew became poisoned. The word became an insult and had an added bite to it.

You are able to feel this sense of discomfort and bite in the word when walking around the Bavarian quarter today. Throughout the neighborhood there are about 80 signs hung up with a drawing on the front and a small inscription on the back. Part of a memorial called the Places of Remembrance, these signs are attached to lampposts throughout the neighborhood. Each of these signs contain one law or a quote referring to a specific restriction that was enforced upon Jewish people starting in 1933 all the way to 1945.

’The time has come. Tomorrow I must leave and, naturally, it is a heavy burden… I will write to you…’ Before being deported, January 16, 1942. Photo by Charlotte Goodman.

Places of Remembrance works alongside another decentralized memorial that is prominent in the Bavarian Quarter – the Stolpersteins, which are small bronze plaques placed in the ground in front of the last place of willing residence of Jews. Inscribed on the memorials are names of Jewish residents, dates of deportation, the camps they were sent to, dates of death and location of death. In contrast, while Places of Remembrance may seem like it is also dedicated to the victims of the Holocaust because it highlights the oppression Jews faced, it really serves as a constant reminder to German citizens how the state turned against its own citizens, their neighbors, through discriminatory laws. It really puts into focus the perpetrators and the mechanisms of persecution and mass murder. The excerpts from the anti-Jewish laws serve as indisputable reminders of their impact on neighbors. In that way, the memorial works as an ode to the victims, but more serves as a reminder to the perpetrator’s city and citizens of events that took place in this place not so long ago.

One word that serves as a constant reminder throughout the memorial, is the word Jew. The memorial’s curators Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock were purposeful about including the word Jew or Jewish into every sign they could so that it was inescapable to the audience who was tormented by these laws. Including these words elicited responses almost immediately. For some, they responded with hate, others with anger, while for others, the signs brought up painful memories. While the memorial was being put up there were people who shouted antisemitic remarks at the workers installing the plaques. “…suddenly someone opened a window and yelled out: Haut ab, Judenschweine!—’Go away, Jewish pigs!’” (Johnson, page 6). This response was shocking to the workers, but also served as a reminder for why the memorial was so necessary. While some people were yelling antisemitic remarks, others were so outraged by the memorial being put up, that they called the police. “’There is antisemitic activity going on’” (Johnson, page 8). A legal battle followed, with 17 signs being taken down and put back up, until finally small plaques were added, hanging underneath the sign, signifying that they were part of a memorial. Before the installment of the memorial though, the artists conducted interviews with people who had lived in the quarter during the rise of Nazism and asked them what their reactions were to their Jewish friends being exiled and ripped from their homes. “One woman burst into tears, and she said, ‘Yes, I saw how they deported them,’ No one wanted to say the word ‘Jew’.” For this woman, the avoidance of the word Jew brought up traumatic memories of the past. (Page 2, Johnson.).

Anti-Semitic signs in Berlin are temporarily removed during the 1936 Olympic Games. Photo by Charlotte Goodman.

Even nowadays the word “Jew” can be used as an insult. Growing up in a small town, I was known as one of the town’s Jews. My family proudly celebrated the Jewish holidays, I received my Bat Mitzvah, and we put a menorah in our window every year for Hanukkah. This put a target on me and my family’s back. After receiving death threats and endless amounts of insults for being a Jew, people who were my true friends even started to question the word. “Can I call you a Jew?” they would ask. “I mean, yeah, it’s what I am”. The use of the word clearly made them uncomfortable.

I did not think there was anything wrong with the word Jew until it was used against me or until my friends became uncomfortable. When I hear it now, in the best of contexts, it still brings a little sting to it. The sting was especially present while walking through the Bavarian Quarter.

Citations

- “Jew Definition & Usage Examples.” Dictionary. Com, Dictionary.com, 2012, www.dictionary.com/browse/jew.

- “Jew.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Jew. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

- Johnson, Ian. “‘Jews Aren’t Allowed to Use Phones’: Berlin’s Most Unsettling Memorial,” New York Review of Books (Blog), June 15, 2013.

- Stih, Renata and Schnock, Frieder. Places of Remembrance in Berlin. Denkmal/Memorial in Berlin-Schoneberg, 1993.