The House of Terror: A Distortion of Public Trust

By Jacqueline Murrer

Whether it be for art, architecture, or history, museums serve as magnificent places to see artifacts from pivotal moments in history or art, and places to fully immerse yourself in another time period. Some may visit museums on their own for fun or to attend various events. More often than not, people visit museums in school classes, or to further some sort of academic research that they are conducting about a certain era, historical figure, or movement. According to the American Alliance of Museums, more than 55 million student school groups pay visits to museums every year. A study conducted by Indiana University found that teachers believe that museums are considered a more reliable source of historical information than books, teachers themselves, or personal accounts by relatives. It is easy to understand why teachers and school curriculum writers put so much faith in museums to educate and inspire students. Museums hold ancient relics from important moments in history “in the flesh,” giving students direct contact with undeniably real artifacts of the past. But what if the information surrounding those objects is conveyed incorrectly?

As museum-goers, we’d like to trust that museums or galleries, especially those funded by governments, are telling history the way it really happened, without omission, illusion, or misconstrued information. Growing up, we’re taught to not always believe what we see on the internet or on television. I never thought that this would apply to museums; places that hold objects of such cultural, religious, and historical importance. That is, until I visited the “House of Terror” museum in Budapest, Hungary. Filled with color and flashy embellishments, loud music filing the rooms, and videos being played on several screens at once, it is easy to get swallowed into the museum, fascinated with all that is being shown to you. However, with attentiveness to detail and prior knowledge of Hungarian history prior to and during World War II, it is obvious that the House of Terror is thriving off of historical revisionism and masking it behind entertainment.

The House of Terror lives within a building that was once a headquarters for the Hungarian fascist Arrow Cross Party during World War II, only to be taken over by the secret police of the People’s Republic of Hungary. The Museum was founded by Hungary’s current prime minister, Viktor Orbán, and is still funded by the government of Hungary today. The museum opened alongside the elections in 2002, and has since been functioning as a political project. The museum’s brochure states that its purpose is to serve as “a memorial to the victims of these [Totalitarian] regimes, including those detained, interrogated, tortured or killed in the building”. Contradictory to its mission statement, the House of Terror’s focus is exclusionary. The timeframe it’s concerned with is 1944-1989, covering the so-called “double occupations” of Hungary, first by Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union. Through this selective approach, the museum omits the extensive history earlier WWII history from before 1944, when Hungary was an ally of Nazi Germany, and the country played a large role in early anti-Semitic actions and the destruction of its own Jewish community. Focusing on a set fragment of dates omits a much larger history, thus violating its trust as a public institution. People visiting the museum in hopes to learn a full version of the history covering totalitarian rule in Hungary may not even notice that they have been given blinders, which draw their attention away from a much deeper and more complicated history than one of simple outside German/Soviet dominations over Hungarian society.

The first glaringly blatant example of the way the museum limits the history it is teaching is through the way the term “occupation” is deployed. Throughout the course of official tours, guides explain how Hungary was a victim of German and Soviet “occupations.” With prior knowledge about Hungary’s stance during World War II, one would know that this was not entirely true. Hungary played a large role in the execution of the Holocaust. In fact, throughout the war, Hungary was an ally of Nazi Germany and it was the Hungarian Arrow Cross that willingly and enthusiastically carried out atrocities against Hungarian Jews after 1944.

Further, the museum reinforces multiple times that the Hungarians were ruthlessly oppressed by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Aside from a very brief acknowledgement of the Arrow Cross, the museum’s narrative, nor the tour guides, never mention Hungary’s responsibility or hand in carrying out the Holocaust. The House of Terror frames Hungary as solely a victim of the Nazi “Occupation”, rather than admitting its role, small or large, during World War II and the Holocaust. To convey the message that Hungary was unwillingly taken over and occupied by Germany and Soviet Russia is simply untrue. A student, or even a mere passerby that is curious or eager to learn about Hungarian history, that visits this museum without a full prior understanding of World War II and Hungary’s position during the Holocaust could have their depiction of history unbelievably skewed. History becomes distorted and mismatched. One could even say that tourists can be “brain-washed” by visiting this museum, as it seems the House of Terror (and the Prime Minister who funded it) are trying to mask a crucial part of history.

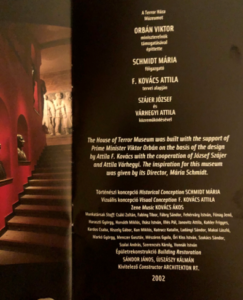

Inside of the House of Terror brochure, where it is stated

that the Prime Minister of Hungary helped fund the museum

The next question we must pose is who do we give the responsibility to make sure that museums are telling the whole truth, and how? This question seems especially important in an era when museums rely increasingly on new technologies and entertainment to attract visitors. Andras Szantó stated in his article, Terror on Andrassy Boulevard, that “to successfully compete with our relentlessly distracting commercial environment, a museum has no choice but to become user-friendly. For these and other reasons, in recent years the line between academic and atmospheric museum design has steadily blurred… museum directors have learned that eye-popping architecture and accessible programming can popularize exhibits and inflate attendance numbers” (Szantó, pg. 45). Thus, how do we hold museum directors accountable for keeping museums transparent and historically reliable/truthful? Sadly, it is clear that in the case of the House of Terror, transparency was not the agenda. The museum was not a purely historical project created as a place of remembrance and academia. Rather, it was created on the basis of politics, in order to blur Hungary’s real involvement during WWII, and to make sure that Hungary maintained a clean reputation.

It is clear that museums are continuing to have a growing impact on modern day education. Statistics show that students develop more attentive and critical thinking skills when they visit museums that correspond to their research and curriculum. But, if students are developing these skills and learning in spaces that are misconstruing history, this could be very consequential to not only their education, but the way that future generations look at historical movements, historical figures, and politics.