Opening my Eyes to Antisemitism’s Development in the Interwar Period

By Caroline Simon

Prior to embarking to Europe on my study abroad program, I expected to confront the horrors of the Holocaust. I thought I knew plenty from classes I have taken, books I have read, and movies I have watched; I was certain, however, that being in the places where these atrocities took place would be an experience different than what I could have imagined. When we study the Holocaust, we study figures like six million, we learn names like Auschwitz, and we consider methods of mass murder in places like gas chambers. Linked to these numbers of victims and sites of mass murder was the broader concept of antisemitism. It was not until I visited the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Budapest, Hungary, that I encountered with full force the omni-presence of antisemitism leading up to the Holocaust. What I was awakened to in my travels and study is the fact that anti-Jewish sentiments in Europe– in Hungary and Austria, specifically– did not exist in the vacuum of the war years when the mass murders took place, but had been prevalent for decades. The extensive anti-Jewish attitude prior to the Holocaust informs the rage and success of Kristallnacht, a night when across Germany, the Nazis burned down Jewish synagogues and destroyed Jewish businesses. This long-standing antipathy towards Jews provides insights to understand how Austrians could organize “scrubbing parties” during which they forced their neighbors and co-citizens to wash graffiti from the streets, standing over them and mocking openly with visible hatred. These incidents point to the fact that while Hitler may have perpetuated the lingering anti-Jewish sentiments of Europe’s 20th century, he did not create it from scratch.

Hungary’s first anti-Jewish law was in 1920, when Adolf Hitler was just entering the political sphere. The numerus clausus law put a quota on the number of Jews allowed in universities while simultaneously defining Jews as a racial group for the first time. Over the next two decades before World War II, Jews struggled to gain political representation and social status. In Hungary a consensus existed that Jews in their land were a problem in need of a solution. It is important to emphasize that all of this happened without Hitler’s direct influence, without concentration camps, and without precedent from other countries.

In 1938, Hungary created a law limiting Jews’ participation in the economy. According to the Law for the More Efficient Protection of the Social and Economic Balance, only 20 percent of Jews (which included those who had converted to Judaism or were born to Jewish parents) were allowed to be involved in the economic life of the country. Later, a more restrictive law was passed, reducing the percentage of Jews allowed to participate in the economy to 6 percent, with Hungary’s legal definition of “Jew” widened to include Jewish converts to Christianity. While these laws did not constitute physical violence towards Jews, they showed a determination to marginalize and isolate the Jews of Hungary. These steps were crucial in informing the later crimes Hungary and Hungarians committed against its Jewish citizens.

The Holocaust Memorial Museum in Budapest allows visitors to trace the progression of insitutionalized antisemitism prior to the Holocaust that led to the ultimate destruction of the Jewish community. Visitors first learn about deprivation– that of property– through pictures and descriptions. Forcing Jews out of their homes was a deliberately antisemitic act that sent the message that they had no power (and now, no home).

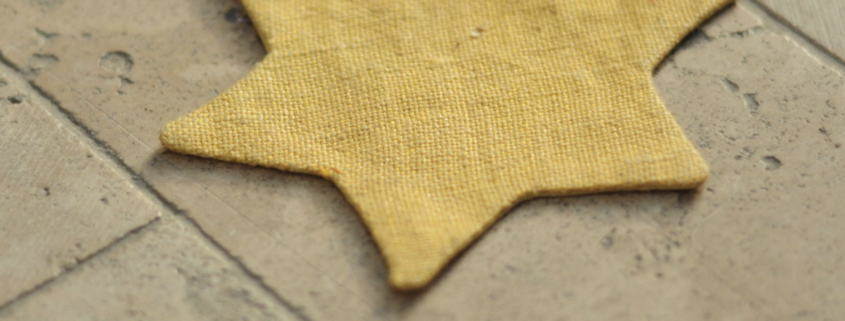

Next came the deprivation of freedom which, among other tactics, was manifest in the enforcement of Jews wearing yellow Stars of David as markers of their position as social outsiders. This practice almost literally put a target on Jews’ backs by identifying them as “others.” Deprivation of human dignity then came in many forms, both in and out of camps. One form of depriving Jews of their dignity came from videos the SS took of them– for purposes of distribution– in labor camps, looking like animals, so everyday people would view them as subhuman. It is disturbing yet telling that this worked, as opposed to the alternative in which people would take pity on them and offer assistance. The assigning and the tattooing of numbers stripped Jews of their personality and identity, and serves as another example of the way the Nazis deprived them of their human dignity. This museum also showed Dr. Josef Mengele’s evil experiments performed on Jews that served to take away their dignity as humans. Deprivation of life happened in part not only through the mass murder in death camps, but also through harsh labor in camps as well as through starvation, disease and shootings in ghettos, and in killing fields in occupied Europe. The museum’s structure effectively conveyed the progression of antisemitism through anti-Jewish laws and practice in Hungary. I was struck by the concept that people had to be complicit in Hitler’s plan in order for it to work and that it took decades of institutionalized and individual hatred to build to a point at which people were eager to unleash it more violently as it was more universally allowed and encouraged.

A striking aspect of Budapest’s Holocaust Memorial Museum was the way it forced visitors to confront what it frames as the point of no return. During early stages of persecution of Jews, the process could have been halted and even reversed. Hypothetically speaking, property could have been returned and freedom could have been restored, and life may have continued on as usual in the interwar period. But once citizens and institutions stripped Jews of their dignity, there was no going back. This is an astounding phenomenon: people let antisemitism get past this point of no return; they accepted increasing repressions that categorized Jews as subhuman and make others see them as such. This broad acceptance of injustice cannot be created in a bubble. Authors Deborah Dwork and Robert Jan van Pelt recount that when acts against Jews increased after the annexation of Austria, though it was the state enforcing it, the elites and working class alike turned a blind eye to the fate of their compatriots. Life went on as usual. It was not one person, one group, or one area that let antisemitism and anti-Jewish law progress so far after World War I that nothing could be done to reverse it. It was, instead, the accumulation of a history of pent-up hatred that allowed this deprivation to succeed.

In Budapest is a museum dedicated to victims of the Nazi and Communist regimes. It focuses on the years of 1944-1989, when Hungary was under Nazi and Communist influence. In focusing on these years, however, visitors are compelled to omit the years preceding 1944 which allowed these eventual regimes to unfold. My thoughts regarding antisemitism mirror this concept. Prior to traveling to Europe, I had assigned the history of the mistreatment of the Jews to the period 1939-1945 when Nazi Germany carried out a war against Europe’s Jews. I had failed to see antisemitism in its larger context. Now I can no longer ignore the history of antisemitism that existed in Hungary and Austria in the two decades before Hitler came to power. Atrocities do not happen overnight with a single law or a single ruler; rather, they result from a gradual buildup– of hatred, in this case– which everyday people experience before being granted the official opportunity to act on their feelings. Jews struggled before Auschwitz was built and before ghettos were created. Their struggle did not come all at once, but increased through time, until it cost them their lives.

Photo source:

- http-hdke.huengalleriesepuletdaylight-photos-museum.png

- http-hdke.huengalleriesgyujtemeny-1collection-objects.png

- http-hdke.huengalleriesepuletdaylight-photos-museum.png