(In)Accessible Spaces: Struggles and Solutions Through the Lens of Memorial Sites

By Sierra Kaplan

800 stairs down, 135 meters deep, 3.5 kilometers long. For the one million sightseers who visit the Wieliczka Salt Mine in Poland every year, these are the extreme lengths taken to complete the journey, and our program eagerly embarked on this tour. However, unlike my peers, I learned these numbers in fear; at the time, I was experiencing chest pain and shortness of breath, which I later discovered to be an acute spinal issue. Yet, to my surprise, the Wieliczka Salt Mine had several measures to accommodate people with various health challenges. Several elevators existed for visitors with physical accessibility needs, visually impaired visitors could bring their guide dogs, and wooden seating dotted the tourist route in nearly every area of the mines. Although potentially overlooked by an ordinary tourist, these measures opened the space for mass arrays of people like me who, without these accommodations, would not be able to experience this extraordinary site that is on UNESCO’s World Heritage list. Therefore, since my visit to the Salt Mine, I cannot help but dissect sites for inclusive, accessible measures, registering every chair or sign. However, in some tourist spaces, like sites of mass genocide, decisions to increase accessibility are not so simple, raising crucial questions about to what extent sites must remain untouched and in their original state.

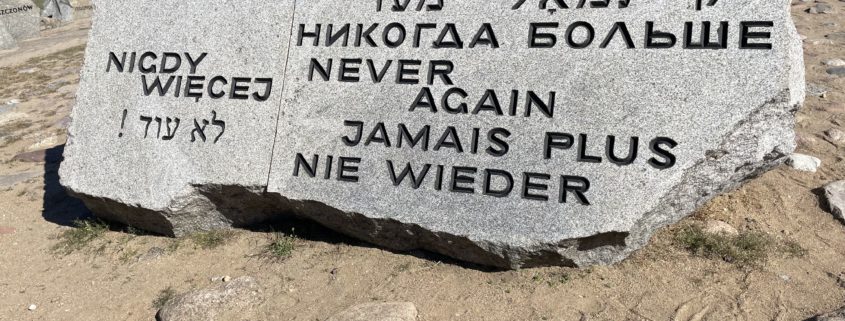

Treblinka is a good case in point. A visit requires covering over four kilometers on unkept, uneven cobblestone paths with little shade and no breaks. Starting at the Visitor Center, we walked through the symbolic entrance gate and along the paved roads throughout the woods. The main cobblestone path, spanning the entire grounds, was worn-down and riddled with split stones and gaps where people may trip. Two kilometers in, we stopped at the monument dedicated to the Treblinka extermination camp. The cobblestone path continues toward this memorial, centered around a tall stone block sculpture dedicated to the Jews murdered at Treblinka. Surrounding this monument are smaller pathways that lead through a field of symbolic gravestones marking cities where Jews murdered in Treblinka came from. However, with 216 gravestones, the walking path is narrow, causing visitors to bump or trip over stones placed close together or lower to the ground. Plus, kneeling on the cobblestone path to pray at the gravestones would be physically demanding on your knees. As my legs nearly gave out, I noticed two older women with canes cautiously walking around the memorial, appearing scared that they might trip. Visitors with walkers or wheelchairs would likely be unable to move through the narrower paths with gravestones. The Ministry of Culture’s decision to memorialize Treblinka’s extermination camp date back to 1955 included the monuments, entrance gates, and these now-deteriorating paths.

Seventy years since the initial commemoration efforts, it makes sense that the stones we walked on were significantly degraded from tourism and age. And throughout this three-hour journey, praying that I would not faint, I pinpointed a singular bench…one bench on a four-kilometer trail. With no water fountains or breaks in the tour, it became easy to feel dehydrated and faint, exacerbated by the sun blazing on our backs. Most of Treblinka’s visitors that I encountered were middle-aged and elderly adults. Since Treblinka attracts an older audience, and 45% of older adults experience limitations in performing daily activities, the lack of accessible options is jarring. Given my own struggles in completing the tour, I could only imagine how difficult Treblinka must have been for the people with mobility issues. Without smooth pathways or seating areas, a tour could become physically overwhelming for anyone, especially people needing accommodations. And although a virtual tour for Treblinka exists, for people without computers or individuals wanting an in-person tour, this may not be the most effective accommodation.

Visiting Auschwitz is not only a grueling physical experience, but also an emotional challenge. For me, my experience of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau often inundates my mind; I cannot casually forget the shivers down my spine walking inside the gas chamber or the inconsolable heartache in learning that my family, who mostly left Poland in the early 1900s, had family members who never left Tarnów and were victims in the Shoah. The information at Auschwitz is so immeasurable and unfathomable to process that I found myself shaking, tripping over bumpy cobblestones unable to see through my own tears. When entering a space like Auschwitz, visitors often experience deep emotional responses which can intensify the already physically demanding tour. With only one break to drive from Auschwitz I to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, we embarked on a six-hour visit with blistering sun rays and physically taxing tour routes. Much of Auschwitz is preserved in its unique, authentic condition. Because of this, Auschwitz remains very inaccessible. At Auschwitz I, most buildings along the tour route first require stairs to enter the building, followed by moments upstairs and downstairs, several of which became treacherous as the stairs were hollowed out due to tourism. These rooms reveal significant mechanisms of Nazi operations, like the standing cells for prisoner punishment or the room filled with preserved piles of women’s hair. When visiting Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the terrain is arduous, with cobblestones worn, crushed, and uneven, so much so that one may easily trip on the tour.

Coupled with the notorious train tracks, it becomes difficult for visitors with mobility issues or wheelchairs; visitors may severely struggle with the uneven pavement and crossing over the tracks for three hours. Visitors could likely fall or experience significant balance issues, making the lack of accessibility options a safety hazard. Entering this sunken barrack with a narrow doorway, unalterable wooden threshold, and muddy paths would prove difficult for wheelchairs and mobility issues, and the rocky floors can be a tripping hazard. I will never forget walking inside the children’s barrack. Upon entering, I felt trapped in its poorly lit, mazed structure, constantly bumping into peers and other tour groups. Inside, tiers of bunks fill the room with narrow, debris-filled paths. It quickly became crammed with tourists, none of which factored in accessibility devices or compared to the hundreds of children suffering in this space. Although several accessible measures exist—like handicap-accessible bathrooms, rentable wheelchairs, ramps in the newer additions to the museum, or virtual tours—much of the original Auschwitz structures remain exclusive to “able-bodied” individuals in good physical health. Thus, those with various physical problems considering an Auschwitz visit must decide whether to miss a majority of Auschwitz, require assistance for nearly the tour’s entirety, or not attend.

Sites like Auschwitz and Treblinka expose the barbaric conditions in which millions of victims lived, forcibly worked, or died. These spaces, these architectural extensions of Nazi dehumanization, in and of themselves are arduous terrains that once perpetuated terror and inhumanity. Thus, creating accessible options in sites of mass genocide brings three things into question: these spaces’ authenticity, their roles as gravesites, and how much, if anything, should be changed or altered. While these historically unique sites undergo continued preservation efforts, they are difficult to adapt to tourism. So much so that the Auschwitz Memorial’s website explicitly states that “in order to preserve the authenticity of the space and its premises, the options of adaptation and interference in its historical structure are limited.” Adaptation and modernization create changes–big or small– that involve an inherent erasure of history, undoing original traces of the space’s past. Thus, despite its good intentions, adding accessible options may be perceived as interfering with the sites’ historical integrity or beautifying death camps. Plus, we must consider that Auschwitz, Treblinka, and other Nazi concentration camps remain mass Jewish gravesites. In Jewish tradition, strict measures exist for sites of Jewish burial, often dismissing choices to build on top of Jewish graves. With this in mind, adding something like a water fountain or stair ramps may disrespect Jewish customs and Jewish visitors. And, if stakeholders agreed that the space could incorporate accessible options, it remains unclear how much can be done. Where must the line be drawn on the spectrum of adding inclusive measures to a space? If too little is altered, it would not stop the debates over needs for more inclusive measures. And if too many changes in the space, it could blur the significance of the space as a site of mass genocide. These ethical issues that memorial sites must grapple with are why I never saw benches on every corner of Auschwitz or a path for the visually impaired at Treblinka.

The Memorial to the Victims of the Nazi ‘Euthanasia’ Murders offers a counterpoint to consider issues of accessibility. Located in the heart of Berlin, this memorial sheds light on the victims of the Nazi’s state-sponsored euthanasia program. It is important to acknowledge that while the installation is not directly a mass murder site like Auschwitz, it is, however, located at the former headquarters of the T-4 program, which influenced the system of mass-murder at extermination camps. The memorial has been adapted to various needs of visitors, making the space informative and accessible. Visitors read from a slanted table at an optimal height for people with wheelchairs to participate. From there, the text is easy to understand, the screens on the table allow for subtitles in several languages, and for the visually impaired, there is Braille. At the site, a straight tactile strip of pavement alongside the table guides visually impaired visitors to the memorial. Then, contrasting tactile breaks indicate where the Braille content is available. The memorial successfully ensures the space remains inclusive, much of which is from the insight of T-4 victims, their families, and disability associations. Perhaps other sites of mass trauma could benefit from amplifying the voices of impacted families or advocacy groups when struggling between preservation and accessibility. As the Memorial to the Victims of the Nazi ‘Euthanasia’ Murders shows, sites can preserve historical memory and simultaneously create an inclusive environment for the space’s audience. Although it differs from memorial sites like Auschwitz or Treblinka, the modern commemorative solutions at the memorial reveal how much may be accomplished when there are careful thoughts about inclusivity for whom this history is so important.

I grew up in a Polish-American Jewish household, where the opportunity to see Auschwitz or Treblinka was something my family and I always talked about but could never afford or tour due to my Grandma Marsha’s ambulatory problems. After experiencing these sites, I can confirm my grandma’s worries about how inaccessible the space would be for her. While my family was not particularly religious, in high school, I learned from a Rabbi about modern interpretations of the Old Testament, and his wisdom inspired me as I thought about these sites. At Auschwitz and Treblinka, I recalled Leviticus 19:14, which asserts, “You shall not insult the deaf, or place a stumbling block before the blind.” When I interpret this proverb, I believe it means there is a responsibility to make accommodations, especially in these Jewish spaces. I grapple with the fact that these sites are Jewish cemeteries, but because these are Jewish cemeteries, losing some of these stumbling blocks allows people from the community, like my grandma, to enter these spaces. While these sites should preserve what remains of the Holocaust, I find that this proverb encourages compromise for the goal of equal access. And we must consider the consequences of inaction. At Treblinka, I was deeply disturbed to witness our tour guide sit on a gravestone commemorating the murdered Jews of Jedwabne as he waited for us to explore the memorial on our own. And at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, tourists sweltering in the heat without any place to sit made their own seats on the original train car used to transport Jews and others to their deaths. Thus, it begs the question: would these people have acted differently if a bench existed nearby, or foldable stools were given? With victims’ families visiting the site over the last six decades, we must recognize how inaccessible spaces may prevent this now aging population from making the trip to pay respect to their loved ones who perished at this site. We owe it to survivors, victims’ families, and even everyday tourists to make any memorial site accessible for grieving, remembering, and emotionally processing these difficult histories. Perhaps if changes were made, then people like my grandma could contemplate visiting these spaces to honor newly discovered relatives.

References

- Auschwitz Birkenau State Museum. (2022). Accessibility / Auschwitz-Birkenau. Auschwitz-Birkenau. https://www.auschwitz.org/en/accessibility/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, March 24). Keep on your feet-preventing older Adult Falls. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/older-adult-falls/index.html

- Lebenshilfe. (2014, September 5). Memorial raised in Berlin for people with disabilities victims of Nazi regime. Inclusion Europe. https://www.inclusion-europe.eu/memorial-raised-in-berlin-for-people-with-disabilities-victims-of-nazi-regime/

- Tourist route – Practical Information. The “Wieliczka” Salt Mine. (n.d.). https://www.wieliczka-saltmine.com/individual-tourist/useful-information/important-information/tourist-route?null=

- Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A., Ćwirlej-Sozańska, A., Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska, A., & Sozański , B. (2019, October 31). Determinants of ADL and IADL disability in older adults in southeastern Poland. BMC Geriatrics. https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1319-4#:~:text=It%20showed%20the%20occurrence%20of,found%20by%20Germain%20et%20al.