Civilians During Polish Uprisings Memorialized in Exhibitions: Men As “Brave” And Women As “Selfless”

By Abigail Wright

Do not think, do not look, persevere, survive.

Do not think, do not look, persevere, survive.

Do not think, do not look, persevere, survive.

In “Around Us a Sea of Fire,” the first exhibition solely dedicated to the fate of Jewish civilians during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, echoes of Jewish resistance rested upon my chest, reverberating through my ears and the concrete walls of the dim “bunker” I was curled into. Hushed voices layered atop one another as the distant hum of destruction roared on—billowing smoke, flashes of red, the unknowing cries of a newborn.

The beat of this one phrase, do not think, do not look, persevere, survive, whispered by a Jewish woman fighting for every second underground, guided me through this immersive exhibit in the POLIN Museum. Phrases like these represented the fate of over 50,000 Jewish civilians who hid in a labyrinth of sewers and tunnels as Nazis destroyed the city above them in a final attempt to eradicate the population during World War II. Instead of staying above ground in their controlled and confined living quarters—the ghettos—the Jews fled below the surface and remained in hiding, escaping and resisting their imminent exterminations.

In the fight for their lives, words were salvation. I had the honor to “meet” just 12 of the civilians through their uncovered testimonies recorded during these unimaginable weeks—a tangible glimpse into the horrors of life and death underground. On the very same grounds where this took place 80 years earlier, I listened to the voices that are often silenced, holding onto every word.

The fervency at which Jewish civilians documented their experiences paved the way for this exhibition, placing visitors in a unique act of resistance through complete immersion—a successful and personal connection to history through quote-driven testimonies. Having visited a few museums prior to this exhibit (and a few more afterwards), the “Around Us a Sea of Fire: The Fate of Jewish Civilians During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising” has lingered due to the intentional use of words and stories.

The focused narrative spotlighted themes of human value, bringing up questions about who has the power to deem a life worthless, who has the freedom to choose a worthy death. As I navigated through the shelter-tombs in which human beings were betrayed by the world above them, I listened to the retellings of civilians jumping out of burning buildings—a testament to the unified demand for liberation, even in death. The need for autonomy and agency in a space where a baby’s first cry is deadly permeated my being through the phrase The child spells doom for us; we must strangle him. It was as if these voices moved my body through the space for me—I was hovering over history in a way I’ve never experienced before.

It was one of the most thoughtful exhibitions I have ever visited—better yet, been a part of—largely due to the intentional curation of these Jewish narratives.

Often, Jewish history is deduced to numbers or told through the lens of aggressors rather than honored through stories and experiences; however, in this exhibition, the Jewish perspective was the only guiding voice. The curators succeeded in sharing these severed life stories by spotlighting Jewish voices without attempting to speak over them. Even the title of the exhibition, Around Us a Sea of Fire, is a direct citation from one of the testimonies. The raw emotion seeping through every word served as a bridge, of sorts, to better understand the atrocities of the time. The destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto was total. The curators scraped together any remaining evidence that wasn’t intentionally destroyed to create a remarkable glimpse into the reality of this history.

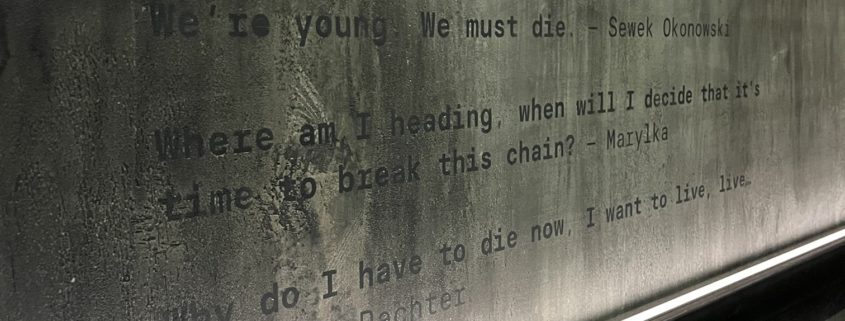

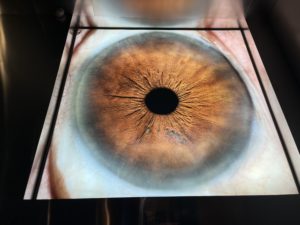

The eye that looks and at which we look, a powerful reminder of the exchange of glances between each side of the Ghetto Wall, a memorialization of those trapped underground as life continued above. Photo by Abigail Wright.

An exhibition devoted to an uprising might be expected to include all sorts of memorabilia, propaganda posters, military uniforms, and accounts of the bravery of men protecting their country in battle. Women, on the other hand, in the background, probably, cooking a meal or sewing a hole or cleaning a wound. Yet, not once did the curators reduce women to the role of fragile “supporters” in this story, even in the excerpt of the mother begging her newborn child to stop crying. In “Around Us a Sea of Fire,” men weren’t portrayed as heroic for fighting, and women weren’t busy keeping the house tidy. No man or woman was above one another; they were individuals bound together in an underground community battling a common enemy, every single body trying to survive in spite of all the odds stacked against them.

And perhaps “Around Us a Sea of Fire” was a spectacular outlier, for another exhibition took an entirely different approach in depicting women during an uprising—one that belittled and patronized women, especially in regards to their male counterparts.

The narrative exhibition at the Warsaw Rising Museum, dedicated to the Polish underground army’s unsuccessful attempt to liberate Warsaw from Nazi occupation in 1944, was difficult to follow—as if different moments in time were dropped from the ceiling and scattered across the floor. Depicting the bloodshed and violence of a resistance movement (which also begged the question: does ‘resistance’ inherently include violence), the museum in its entirety was disorderly and unreachable.

The chaos closed with a recently-opened temporary exhibition: “The Heroine’s Journey,” an examination of the experience of women during the Polish Uprising in Warsaw in 1944. With walls bathed in a Barbie-toned pink, this exhibit was disconnected from the rest of the museum. The exhibition curator turned to mythology in an attempt to expand “heroism” to include femininity, promising visitors that “mythical goddesses will show us the way.” The American Girl Doll-esque room—complete with makeup, dresses, and purses—compared relevant women in the movement to different goddesses in a misguided effort to highlight their “inner strength” during war.

Words have the power to skew perceptions and alter narratives, and the undertones of this exhibit permeated with patronization and even misogyny. The most jarring display was an informational plaque accompanying a recovered makeup compact: Medical Orderly “Luna” had kept the compact in her shirt pocket, and when she got shot in the chest by a Nazi, it lessened the impact and saved her life. Described as an escape from death by chance, or rather the “desire to look nice,” this perpetuated a common theme in the room—in the midst of war, women were meant to look presentable.

For an exhibit meant to amplify the female narrative, the entire curation seemingly brought women down, never portraying them on the same level as men. Women in the military are described as “selfless,” while men are “brave” to protect their nation. While feminist ideals vary throughout generations and nations, the behavior of women at the time perhaps an act of autonomy and sense of identity, I couldn’t help but wonder why this exhibit was distinctly separate, both thematically and physically.

The curator’s intent, according to an interview with Vogue, was to document the heroism of civilian women—whether they be fighting on the front line or fighting to maintain everyday life in basements—and equate their stories to their male counterparts. I noted the continual thread of “heroism” as a limitless act, one that cannot be confined to gender; however, as I walked through these pink walls, the honest intentions unraveled quickly, leaving a particularly bad taste in my mouth.

Walking through this pink room just one day after the previous exhibition, “Around Us a Sea of Fire,” was a complete shift, largely due to the language of narration and the drastically different depictions of women, and civilians, even. Throughout both exhibitions, the different use of words completely altered my experience. The bridge between words and connection ultimately fell flat in “The Heroine’s Journey,” and the attempt to equalize women only knocked them down further. The intentional usage of language in “Around Us a Sea of Fire” contributed to its impact; the curators amplified the voices that are usually silenced, leaving a tremendous impact in their wake.

Language matters, and perhaps leaving space for people, especially women, to speak for themselves is more than enough.