Hitchcock, Welles, Kurosawa, Riefenstahl?

By Luke Burke

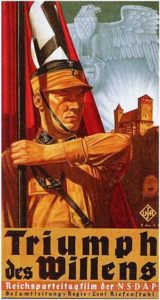

I was unsure of what to do on my first night in Vienna. I wanted to do something educational, and looking back on it now I think what I did was more thought provoking than any museum exhibition I could have stumbled upon. Recommended by my teacher, I went to see Leni Riefenstahl’s 1934 film Triumph of the Will, an iconic film which documents the 1934 Nuremberg Rallies by the Nazi Party. Before watching Triumph of the Will, I was almost completely unaware of who this famous female filmmaker was and the fact that she was one of the biggest propagators of the Nazi Regime and its terrifying agenda.

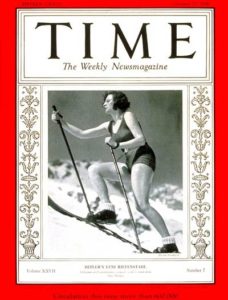

Along with many of her other works, such as her film on the 1936 Berlin Olympics, this documentary was an instant worldwide success. With its release, Riefenstahl was propelled into the spotlight as one of the premiere directors of the era, and is still considered as such by many. Why is this woman so revered if her focus was to build up the image of Nazism and Adolf Hitler? The answers, I found, became evident after my screening of the film, and signal the dangerous side of documentary filmmaking.

Film is meant to tell a story and evoke emotion, which is exactly what Riefenstahl does, although it is disconcerting when you realize she does this while creating such a blatant piece of propaganda. Triumph of the Will manipulates and tricks the viewer out of thinking about what the Nazi party actually stands for, and in today’s context, makes you forget for a second the outcome of Nzi rule. After watching, I was grappling with why I was fascinated by the film and not cursing at the images on the screen. It would seem that even I was captivated (or manipulated) by Riefenstahl’s work some 85 years later.

Riefenstahl does this because she is objectively a great filmmaker. She makes one believe what she has shot was unstaged. Through the way she warps the events, her documentary actually runs like an impressive epic or drama. The story is of a long awaited hero’s arrival. By the first scene one is drawn in by the beauty of Germany’s sky and the peaceful bird’s eye view of a city. Then comes a wide variety of carefully selected and captivating shots that the audience thinks happened without orchestration. With almost constant motivational music, we see wide shots of rows and rows of well-organized soldiers stomping to a fixed beat with shiny helmets acting as one body. Close ups of beautiful women and babies smiling as if they had seen the second coming of Jesus Christ are juxtaposed with grandiose crowds all chanting in unison and saluting Hitler. Young boys wrestle and have the time of their lives. Other similarly perfectly choreographed scenes show people coming together. All of these images show a great sense of might and are all displays of Germans having a great time through the joining of a common cause. It is inspiring, almost a utopian-like world. The viewer is assaulted by the sheer mass of people, as if their cause is universal. It plays like a well composed symphonic piece.

Leni Riefenstahl celebrates Nazi ideology of the superiority of the Aryan Germans, which served as a cornerstone of the later genocide of Europe’s Jews, Roma and the disabled, and launched a destructive World War that lasted for six years. What’s deeply troubling is this powerful imagery, removed from its historical context, can be gripping and even inspiring. This is why she is so revered. She does this by morphing this radical party’s rally filled with hate, rage, and angst into something that you yourself almost want to be included in. I am not saying I want to be included, although at points I fell victim to the drama of it all. Those shots are exactly how she hooked everyone into supporting the Nazi regime.

Manipulation is dangerous. When the people are made to believe that the artificial is real they become brainwashed. They will view the world unrealistically. They will act in ill advised, uninformed fashions. This is especially dangerous in the case of Nazism.

Humans are impressionable, and with a medium like film which projects such large images right before your eyes, it is so easy to become captivated by the images you are watching. Riefanstahl uses her filmmaking and storytelling skills to give something that is almost completely staged and rehearsed with the stamp that it is all exactly what happened during the Nuremberg Rallies. This is problematic.

With no preface whatsoever (such as was the case when I viewed it in Vienna), the film can give viewers today a false sense of history and memory–the false sense of comradery between the high up officials and the people. It does a great job of making the Nazi Party leaders seem like caring, kind individuals. This film is seen as a historical documentary, but the manipulation of images and emotions has created something that does not align with the reality of the history it portrays, something that begs the question of why we still watch this film. The film blurs the line between Riefenstahl’s mission of making the rallies an awe-inspiring event and the larger truth about Nazi rule. Something which, as we have seen, can lead a country down a horrifying road.

Photo sources: