Underdogs: How Unlikely Figures Present Hope for Change

By Harrison Vogt

A Movement in Communist Poland Provides Hope for Modern Climate Change Activism

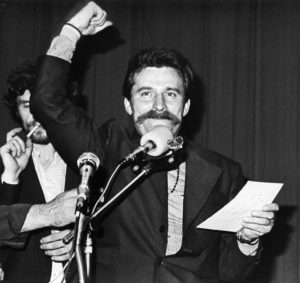

Figure 1: Lech Wałesa, leader of the Solidarity Trade Union. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strajk_sierpniowy_w_Stoczni_Gdańskiej_im._Lenina_22.jpg

In August 1980, The Solidarity Movement arose from a series of protests and strikes led by Lech Wałesa and his “Solidarity” Trade Union in response to hikes in daily goods and oppressive action taken by the communist government. The Lenin Shipyard strike established a national push for independent trade unions and a broader democratic push. This development established opposition as a permanent feature of the Polish Political landscape and allowed for more oppositional demands to be voiced. On a broader scale, this development led to the collapse of communist rule in Central Europe and the broader Soviet Union a decade after Wałesa first called for change within the Lenin Shipyard grounds.

In 2015, Greta Thunberg, and her high school friends skipped class and sat in front of the Swedish Parliament under the name of “Fridays for Future”. Within the past six years, the movement has grown to millions of followers and is actively convincing local, national, and global governments to agree on drastic action on climate change. Thunberg’s rise to success is painted with the same classic David versus Goliath scenario as the Solidarity movement faced. Despite facing stacked odds against their causes such as students calling for governmental action or workers calling for change in an oppressive and dysfunctional government, two ordinary figures rose as leaders. Who could have thought that a single individual in a collective, oppressed nation would lead to the toppling of its whole system? Who could have thought that the major voice in climate action is a teenager? The two scenarios, while in separate contexts, present underdog stories of workers and citizens against unfathomable tasks.

Figure 2: Crowd of Solidarity supporters in 1989. Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ec/Wybory_1989_2.jpg

When the Solidarity Strike began in 1980, those seeking to create change during the 1970s in Poland faced a daunting reality of communist dominance to the local level. Despite this setback, Wałesa came out as the face of a leader of change. The strikers demanded not only their right to exist as a union, but a broader list of 21 demands including a right to freedom of speech. These demands had been unfathomable. Yet, Wałesa led the strike to its success with his negotiations with the government. Even more so, he did this in the light of being a former electrician and being the underdog character.

In 2019, after four years of sizeable growth in her movement, Thunberg published her first book, No One Is Too Small To Make A Difference. This nod in its title to a cliché phrase highlights the importance of speaking-up no matter the perceived power of your voice. The book represents a collection of speeches Thunberg gave at rallies. All the while, she received more support for the cause of governmental action on climate change. In doing so, Thunberg bucked the criticisms of being a student and not having political influence through her actions. Her lead of Fridays for Future has allowed for substantial change to occur and is gaining a platform for more change.

Figure 3: Greta Thunberg, an unlikely face for a global movement. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greta_Thunberg_4.jpg

For both the 1980s oppositional groups behind the Iron Curtain and modern day climate activists, the centering of those movements around seemingly ordinary figures fights the idea of an unfathomable feat of change. For example, Lech Wałesa was an electrician at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk. A decade prior to his face becoming a symbol of a national movement, he would not have been recognized as anything more than the electrician. For Thunberg, the face of a student is branded poorly in gaining influence. Yet, both faces are responsible for movements of global significance. Both mean that change is occurring through the speaking up of underdog characters.

The Fridays for Future movement, while not yet successful in reaching its end goals, can find precedence in the underdog stories of the Solidarity Movement in Poland. Fridays For Future provides structure and unity for students’ climate change demands just as the Solidarity Trade Union allowed for more than just workers’ rights to be pushed. Greta Thunberg capitalizes on the lack of action on climate change, her goals find collective support from hundreds of thousands of people across the globe. In addition, she has the social status as a student with the ability to lead millions of people. Additionally, the unlikely face of the movement is similar to the unlikely face of the average citizen toppling the communist regime. While it seems a Goliath task to get governments to reach climate agreements, nearly a decade ago, any action on climate change was considered taboo. The current success of Fridays for Future presents a broader hope for advancing the movement. Doing so in the light of a major challenge has been proven to be successful in the past.

Reference:

Pakulski, J. (n.d.). The Solidarity Decade. ANU PRESS. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from

http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p24291/pdf/ch079.pdf.

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. (n.d.). Marzec 1968. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Retrieved

October 11, 2021, from

https://ipn.gov.pl/strony-zewnetrzne/wystawy/marzec68_w_krakowie/content/index_eng.

html.

International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. (2020, July 20). Poland’s Solidarity Movement

(1980-1989). ICNC. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from

https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/polands-solidarity-movement-1980-1989/.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, September 25). Lech Wałęsa. Encyclopedia

Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lech-Walesa

Jarosław Szarek, Ph. D. (2020, August 5). 8 May 1945 – Polish perspective. Institute

of National Remembrance. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from

https://ipn.gov.pl/en/digital-resources/articles/7333,8-May-1945-Polish-perspective.html.

InYourPocket. (n.d.). The story of the Gdansk Shipyards. The Story of the Gdansk Shipyards.

Retrieved October 11, 2021, from

https://www.inyourpocket.com/gdansk/The-story-of-the-Gdansk-Shipyards_73707f.

Thunberg, G. (2021). No one is too small to make a difference. Penguin Books.

Image Credits:

1: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strajk_sierpniowy_w_Stoczni_Gdańskiej_im._Lenina_22.jpg

2: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ec/Wybory_1989_2.jpg

3: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greta_Thunberg_4.jpg