Reconciliation and Reconstruction in the 21st Century

By: Katelyn Olsen

When working with the memory and reconciliation of a place of destruction, there are three options for moving forward. You can do nothing, leaving the scars to speak for themselves. You can rebuild what once was, making a replica of once stood and what will stand again. Or you can start from scratch, building something entirely new.

The question of what should be done moving forward is especially difficult in places such as Dresden, Germany. A well connected city during World War II, it was bombed on February 13, 1945. To this day, the city struggles with its mixed identity, being both a perpetrator and a victim.

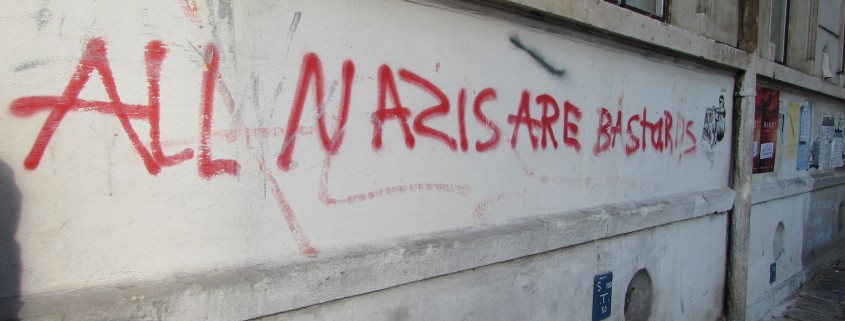

As we follow our guide, Janosch, to the heart of Dresden, one of the first things I notice on our walk is a small graffiti display, about chest height, on the side of the wall. “ALL NAZIS ARE BASTARDS” is sprawled across the wall in bright red spray paint, instantly making it clear to me that Germany’s Nazi past is ever-present in at least some of its citizens’ minds.

As we follow our guide, Janosch, to the heart of Dresden, one of the first things I notice on our walk is a small graffiti display, about chest height, on the side of the wall. “ALL NAZIS ARE BASTARDS” is sprawled across the wall in bright red spray paint, instantly making it clear to me that Germany’s Nazi past is ever-present in at least some of its citizens’ minds.

Furthering my point, our next stop is at a memorial for Jorge Gomondai. On April 6, 1991, Gomondai was taking a tram home at which point a group of Neo-Nazi youths attacked him and threw him off the tram. He died from the injuries a few days later. Jorge Gomondai’s death is notable in Dresden’s history because he was the first victim of Neo-Nazi racism in the city. Even today, Neo-Nazis are a big issue in Saxony.

The presence of these racist and anti-foreigner attitudes so many years after the Nazi and socialist regimes in Eastern Germany forces you to wonder what it will take for peace and reconciliation to take up permanent residence here, or if it is even possible.

As we keep walking, we eventually reach where Janosch tells us to stop. Here he attempts to make it very clear that we are about to cross the line that separates what was and was not bombed. Any buildings that may appear old were rebuilt after the bombing.

What strikes me most about this reconstruction is the normality of it all. It burned down, so we rebuilt it. While it is never that simple, the sheer amount of reconstruction sure made it seem that way.

We first see the complications of rebuilding upon arriving at the Frauenkirche, a church at the center of town. The Dresden bombings led to the collapse of the church in 1945. While the church appears to be from the 18th century, its reconstruction began in 1993 following the reunification of Germany.

The Frauenkirche was not simply rebuilt, however, as elements of the original building were used to remind the public of its troubled past. From the outside, dark bricks speckle the overall sand-colored building. Despite first looking like a cosmetic choice, these dark bricks were actually recovered from the original building and were then reused for its reconstruction. Thus, reminding everyone of its tragic downfall.

By rebuilding the church in this way, it subtly acknowledges its past without overshadowing the church as a whole. In addition, its reconstruction can be seen as an attempt at reconciliation with funding for the rebuilding coming from German, English, and American donors. By bringing in the foreign entities that destroyed the church, Dresden is effectively building a more reconciled and peaceful future.

Our next stop, the Dresden synagogue, varied greatly from the Frauenkirche. Burned down during Kristallnacht in 1938, the Jewish community was originally unsure of what to do with the empty space that remained.

The decision was ultimately made to build a new synagogue and community space on the land. A key point to the decision to build a new complex on the land was the fear that reconstruction of the former synagogue would deny the atrocities that happened both during Kristallnacht and the Holocaust as a whole. The new buildings are careful not to overshadow the painful history of the synagogue either, with the space between them evoking thought about the past and growth in the future. The past is evoked from the old synagogue’s outline and the growth from the orchard.

The grounds of the New Synagogue and Jewish community center, looking at the community center. You can see the faint lines of the old synagogue on the ground.

While it is easy to sympathize with the hardships that accompanied the destruction of both of these buildings, you find yourself having a hard time likening them to each other too much. The Jewish synagogue was destroyed on a night where Jews all across Germany were personally attacked and victimized by the Nazi party. The acts were full of hatred, giving an insight of what was to come. In comparison, the Frauenkirche was a casualty of war within the land of the perpetrators. While destruction was the main purpose of the bombings, its purpose was also to aid in the end of World War II.

Herein lays the difficulty of memory work. How do we memorialize both the synagogue and the Frauenkirche, without taking away from the suffering of either? How can you acknowledge a group’s suffering, even if they aided in making another group suffer? In many ways, you end up with more questions and uncertainties than answers and assurance.

Dresden, as a whole, is clearly struggling with these questions as they move further into the 21st century and further away from its socialist times. Despite the presence of Neo-Nazis in the area, the city appears to be getting closer to reconciling with its past and creating a more peaceful future with each passing year.