Budapest’s Memento Park: An example for America?

By Caroline Bartholomew

There is more to a monument than it’s physical presence — there is also the story behind who put it there and why. While these details are often overlooked, they are a crucial part of understanding the bigger picture and meaning of the monument. Two examples of how countries today are dealing with monuments that symbolize a troubled past are Hungary and the United States.

There is more to a monument than it’s physical presence — there is also the story behind who put it there and why. While these details are often overlooked, they are a crucial part of understanding the bigger picture and meaning of the monument. Two examples of how countries today are dealing with monuments that symbolize a troubled past are Hungary and the United States.

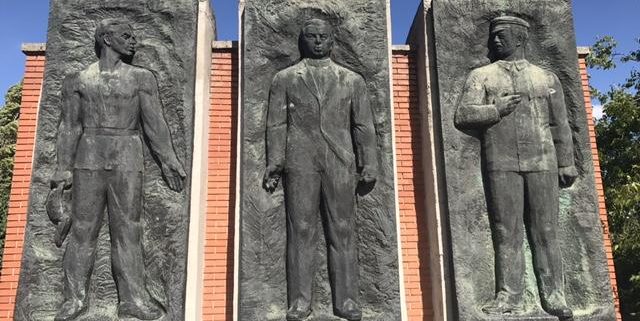

After communism ended, Memento Park was built in Budapest to house 42 statues from the Soviet era that had not yet been destroyed. Rather than trying to eradicate all memorials and statues from the last 50 years, Hungary saw this as an opportunity to “keep [their] historical memory alive and to strengthen citizens’ sense of responsibility and commitment to sustain democracy,” said Zoltán Pokorni, Hungary’s Minister of Education from 1998 to 2001.

Although it is lacking a lot in terms of details and descriptions for each of the statues, Memento Park is a step in the right direction toward preserving and contextualizing decades of Hungarian history overshadowed by Soviet oppression. In this case at least, they are not trying to erase or hide it — they want to put it on display as a reminder of the hardships Hungarians endured.

Visiting Memento Park immediately reminded me of the protests happening at home to remove Confederate monuments from public spaces. If Budapest could deal with its oppressive monuments so efficiently, can’t the U.S. do the same? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple because where Hungarians appear to be united around an understanding that the communist rule was horrific, America remains divided about how Confederate monuments should be handled. According to a poll taken in August, 54 percent of American adults said the statues should remain in public places, 27 percent said they should be removed and 19 percent said they don’t know what should be done.

One problematic aspect of these monuments is that many of them were built during the Jim Crow era and the civil rights movement as a symbol of white supremacy. Radley Balko of The Washington Post writes that “certainly many of these monuments were constructed shortly after the Civil War, and for those, there’s more merit to the argument that they’re legitimate war memorials, immoral as that particular side of the war may have been. But the newer monuments have never been about memorializing the war dead. They’re about signaling opposition to the civil rights movement, or just plain intimidating black people.” Because of the civil rights movement, America has made progress in terms of equal rights, so it seems natural that monuments commemorating racists and white supremacists should be taken down. In addition to the historic symbolism, the Charlottesville riot shows how these memorials can “become a rallying point for violent groups, including white supremacists and the KKK,” writes David Graham for The Atlantic.

One problematic aspect of these monuments is that many of them were built during the Jim Crow era and the civil rights movement as a symbol of white supremacy. Radley Balko of The Washington Post writes that “certainly many of these monuments were constructed shortly after the Civil War, and for those, there’s more merit to the argument that they’re legitimate war memorials, immoral as that particular side of the war may have been. But the newer monuments have never been about memorializing the war dead. They’re about signaling opposition to the civil rights movement, or just plain intimidating black people.” Because of the civil rights movement, America has made progress in terms of equal rights, so it seems natural that monuments commemorating racists and white supremacists should be taken down. In addition to the historic symbolism, the Charlottesville riot shows how these memorials can “become a rallying point for violent groups, including white supremacists and the KKK,” writes David Graham for The Atlantic.

Supporters of keeping the statues argue that removing them would erase parts of American history from public view while opponents argue that not only do the statues commemorate an era of racism and slavery, but they also do not provide the correct historical context for today’s citizens to understand and draw on lessons from the past. This side of the argument is articulated well by New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu: “They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, ignoring the terror that it actually stood for … They may have been warriors, but in this cause they were not patriots.”

One of the major problems is that the monuments lack any kind of historical context. In Birmingham, AL, Mayor William Bell wants a monument to the Confederacy moved to a local history museum where people can get the proper background information. “In Auschwitz, in places like this, they still maintain those ovens to tell the story of the attempted annihilation of the Jewish people,” Bell says in The Atlantic. “This monument that’s here in Birmingham does not tell the true story of what the Confederacy stood for: It was the suppression of people simply because of their color. It was a defiant act against the United States government.”

Removing the statues and memorials does not mean that the Civil War era in American history will be forgotten, just as removing communist-era statues does not mean communism never happened or that people will forget how the country suffered. Schools will still teach about the Civil War, just as schools in Hungary still teach about communism.

Although Hungarians may agree about the horrors of communism and have found a solution for the monuments of that era, they are still struggling to come to terms with their role in World War II. While the government promotes one narrative that all Hungarians were victims of the “German occupation” in 1944 and are therefore not responsible for deporting hundreds of thousands of Jews to Auschwitz, another part of the population knows this is not correct. In this case because the Memorial to the Victims of the German Occupation is relatively new and the government who commissioned it is still in power, protesters of the monument have taken it upon themselves to create a living memorial to counteract the official one. By placing personal objects, signs, explanations and holding meetings, the protesters are explaining the correct historical context of the monument. Rather than trying to have it removed, they find that this is a more effective way to explain what actually happened during World War II.

Although Hungarians may agree about the horrors of communism and have found a solution for the monuments of that era, they are still struggling to come to terms with their role in World War II. While the government promotes one narrative that all Hungarians were victims of the “German occupation” in 1944 and are therefore not responsible for deporting hundreds of thousands of Jews to Auschwitz, another part of the population knows this is not correct. In this case because the Memorial to the Victims of the German Occupation is relatively new and the government who commissioned it is still in power, protesters of the monument have taken it upon themselves to create a living memorial to counteract the official one. By placing personal objects, signs, explanations and holding meetings, the protesters are explaining the correct historical context of the monument. Rather than trying to have it removed, they find that this is a more effective way to explain what actually happened during World War II.

The format of a living memorial is effective in Budapest because Holocaust survivors or their children are still alive to share personal stories. In America, the Civil War took place over one hundred years ago and anyone born a slave has passed away, so this type of response would be more difficult. Even though slavery ended so long ago, monuments to the Confederacy are still a major discussion point because systematic racism and oppression prevented dialogue from happening, much like communism prevented dialogue about the Holocaust from happening in Hungary.

While at Memento Park, it’s hard to shake the feeling that someone’s watching you. Communism ended over 20 years ago and no one I know ever had to experience the terrors of a communist rule, and yet walking through the park give me such an eerie feeling. I was not expecting to feel anything, but the towering bronze and stone statues made me eager to leave the park and continue on with the rest of my travels. I know that communism is a thing of the past — I can study it and move on with my day — and I don’t have giant monuments glaring at me as a constant reminder of an oppressive government.

African Americans who see monuments to the Confederacy every day can’t just walk away and go on with their lives because the fact that these monuments still exist in public spaces without any explanation says that America as a nation still honors people who fought to oppress them. No one is trying to say that the Confederacy never existed or never won any battles, but we as a country need to recognize what these monuments mean to a large portion of our population. It’s time for America to acknowledge its past injustices and it should use Budapest’s Memento Park as an example of a solution.

African Americans who see monuments to the Confederacy every day can’t just walk away and go on with their lives because the fact that these monuments still exist in public spaces without any explanation says that America as a nation still honors people who fought to oppress them. No one is trying to say that the Confederacy never existed or never won any battles, but we as a country need to recognize what these monuments mean to a large portion of our population. It’s time for America to acknowledge its past injustices and it should use Budapest’s Memento Park as an example of a solution.