What is Henryk Reiss’s Identity? The Struggle of Polish-Jewish Identity During and After the Holocaust

By Jack Yoon

When studying the Holocaust, there is a generalized narrative that all Jews were either sent to a camp, trapped in a ghetto, or hidden away from society. In our understanding of the Holocaust today, there is little recognition of Jews who changed their identity as a means to survive. Since the majority of Poland’s Jews were murdered as part of the Holocaust, the range of personal stories that scholars and educators have had access to is limited. In retelling the thousands of stories by survivors, an almost generalized narrative has formed, dominating our understanding of what all Polish Jews experienced during the Holocaust. To students like me, it seemed impossible for a Jew hiding using false papers in occupied Poland to avoid being recognized by the Nazis due to official records or being reported. That is why when visiting the Galicia Jewish Museum for the first time, I was surprised to learn the story of Henryk Reiss, who, although a Polish Jew, managed to survive the Holocaust by adopting a secret identity. This secret identity was adopted through the acquisition of false “Aryan papers,” which gave Henryk a new Polish Catholic identity to cover up his Jewish background. Learning about Reiss’s story not only showed me that there were other ways people found to survive the Holocaust outside of the generalized narrative, but also that, through enough effort, it is possible for one to officially change their identity while remaining true to their lineage.

When visiting Warsaw, walking through the physical spaces of the former Jewish Ghetto and hearing stories from our guide, Konstanty Gebert, I was shocked to see how formal the divide was between Polish Catholics and Polish Jews under German occupation. Although the streets linking the former ghetto with the rest of Warsaw are fully connected today, between 1940 and 1943, the two parts of the city were completely separated by a wall. When Professor Gebert showed us photos of what the streets we were on looked like during the war, I was surprised to see how different the divided spaces were compared to today. In one of the photos, a tram line for Catholics ran through the ghetto, with towering brick walls on both sides of the narrow street. The tram moved through a corridor that maintained a pre-war normality, whereas on the other side of the walls, German brutality ruled across the ghetto. A footbridge was built that allowed Jewish residents to move from one part of the ghetto to the other, passing over the tram and reinforcing their sense of being completely sealed shut inside. This physical separation in Warsaw showed the divide in identity that the Nazis created. In these new conditions, Henryk Reiss was no longer Polish and Jewish, but only Jewish in the eyes of the Nazis, and would have little chance of surviving the Holocaust if trapped in the ghetto. With this still in mind, an exhibit at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow told a different story that existed outside this hopeless narrative. The story told in the museum illustrated the possibility of overcoming the walls of identity imposed by the Nazis to have a chance at survival.

When I stepped into The Galicia Jewish Museum for the first time, its temporary exhibition named “Henryk Reiss Must Cease to Exist” was a shock to me as it told the story of how Henryk Reiss and his family survived the Holocaust by hiding their Jewish identity. This not only broke the generalized narrative that I have only been exposed to, but it also introduced me to the challenges that come with actually changing your identity. Established in April 2004 by Chris Schwarz, The Galicia Jewish Museum aims to offer a new perspective into Jewish history by having visitors “challenge the stereotypes and misconceptions typically associated with the Jewish past in Poland.”1 Schwarz not only wanted to bring awareness towards the Jewish society destroyed by the Holocaust, but also to preserve its memory in the present by renewing Polish interest in Jewish culture. Although small, hosting only two permanent exhibitions, the museum also rotates between a few temporary exhibitions that help shine light on lesser-known topics. By publicly displaying lesser-known topics such as Henryk Reiss’s story, the museum is able to recover lost stories from the Holocaust that can further expand and challenge our understanding of past events.

Located in a former industrial space in the Kazimierz neighborhood, the museum at first seemed run down and abandoned, almost as if it had nothing to offer compared to other Holocaust museums I have visited, which were much more modern and impressive on the outside. My view and interest towards the museum changed, however, when I saw their exhibit “Henryk Reiss Must Cease to Exist.” The exhibit remembers a lost experience during the Holocaust, where tens of thousands of Jews changed their identity to be Polish Catholic in hopes of surviving and escaping the ghetto. What makes this exhibit special is that it is based on Henryk Reiss’s post-war memoirs while also displaying “one of the most complete collections of preserved ‘Aryan papers’ used by a specific family.”2 When first entering, an introductory text gives a brief background to visitors not only about the exhibit and Reiss’s story, but also about those who used false “Aryan papers.” Learning about these “Aryan papers” for the first time, I was surprised by the power that obtaining false documents had as a potential path towards safety. For a Jew wanting to escape the ghetto, having “Aryan papers” was the only legal form of identification that could allow you to potentially cover up your real identity when questioned. It was a shock to see that even though tens of thousands of Jews possessed some sort of false documents where “it was common knowledge that many Jews were living on Aryan papers,” such a story wasn’t taught in my previous educational experiences.3

The story that Henryk Reiss tells was not just one of a simple identity change, but a dramatic experience full of loss and hope. When walking through the exhibit, it not only tells Reiss’s journey during the war through Poland and Hungary, but also his post-war experience in France and Australia. From the start, Reiss’s story shows the flexibility of identity, as with the German and later Soviet invasion of Poland, he and his family would flee east to end up in the Soviet occupation zone. This is where he would first change his nationality from Polish to Jevrey (Russian for Jewish) in hopes of his family’s survival in the Soviet Union. However, with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Reiss would again tamper with his identity by altering Jevrey and replacing it with Pole in his passport to avoid being immediately identified as a Jew by the Germans. Now living under German occupation, in order for Reiss and his family to truly be safe, they would all have to cease to exist by destroying any evidence of their previous Jewish identity. The first “Aryan papers” Reiss and his wife obtained were birth certificates they bought belonging to an existing Polish married couple. With these certificates, Henryk Reiss became the Catholic Piotr Daraż. It was only in the following months after moving to Krakow and then Warsaw, that the Reisses obtained all the other documents needed to allow them, a Jewish family, to successfully live on the non-Jewish side of the city posing as Polish Catholics.

With these false “Aryan papers”, Reiss had the means to argue that he and his family were not Jewish, but Catholic, by becoming the Daraż family. However, the exhibit also uniquely demonstrates the continued dangers and risks Jews faced in German-occupied Poland. Although the documents gave some feeling of safety, for a Jew living under false Aryan papers, any ordinary encounter in public where someone randomly suspected that they were Jewish could still mean disaster. When walking around Warsaw with Professor Gebert, one thing about life in the ghetto that stood out to me was that the Nazis were supposedly able to tell who was Jewish or not based on one’s appearance and attitude. Not only did the Nazis create physical barriers to separate the Jews, but they were also able to suspect the real identity of Jews through minor things that most would not think of, such as the condition of their clothing or if they seemed malnourished. As a result, for Reiss, this was the most challenging part of changing his identity as he was not only Piotr Daraż by name, but he also had to perfectly play the role of Daraż out at work and even during his sleep. His fear of unconsciously blurting something out in his sleep that would uncover his true identity illustrated how uncontrollable his fate really was. Even though he had “Aryan papers,” he still had to constantly rely on the random people he met throughout his journey, whose attitudes ranged from friendship to bringing mortal danger, in hopes of maintaining his new identity. Once Reiss’s wife was interrogated by the “Blue Police” and the Gestapo under suspicion of being Jewish did the Reisses flee towards Hungary. Disguised under their false Christian identities as Polish refugees, the Reisses would remain in Hungary until the end of the war.

Although Reiss and his family survived the Holocaust through the use of “Aryan papers”, they were also among the very few who were successful. Almost none of Henryk or his wife’s family and friends survived, as around 3 million Polish Jews were killed. The introductory text of the exhibit also points out that while it’s “assumed that tens of thousands possessed some kind of false documents,” it’s known that only a small number of them survived the war.

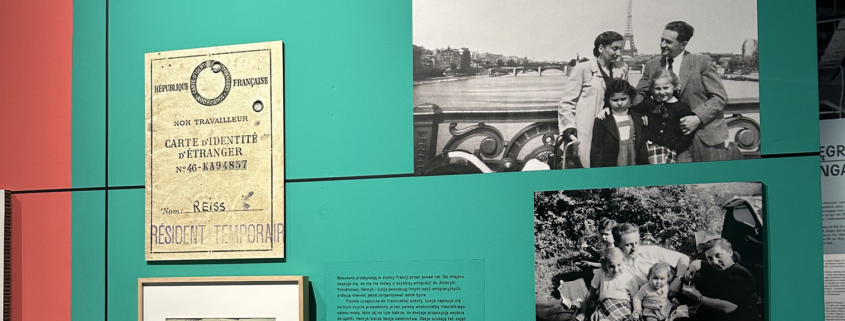

Reiss and his family happily publicly reconnecting to their Jewish identity in Paris. Photo by Jack Yoon

Once the war in Europe was over by May 1945, it was here that Reiss had to decide if he wanted to identify as the Jewish Henryk Reiss or the Catholic Piotr Daraż. He also needed to decide where he and his family would settle. In addition, the growing wave of violence in now communist Poland against Jews raised important questions, like whether the Reisses would return home and what their post-war identity really was. Although Reiss could have returned to the only home he knew in Poland under his false Christian identity, he and his family chose the free world beyond Europe in order to openly reclaim their Jewish identity. However, since Reiss destroyed all the pre-war documents that identified him and his family as Jewish, it would only be after a several-month-long process in Paris that Reiss and his family formally reclaimed their pre-war Jewish identities. The Reisses were resurrected, and the Daraż family ceased to exist. Once reconnected to their Jewish identity, Reiss and his family were able to emigrate to Australia in 1948 as Polish Jews. Piotr Daraz became once again Henryk Reiss.

The Galicia Jewish Museum’s exhibit, “Henryk Reiss Must Cease to Exist,” reveals a story about the Holocaust that I thought seemed impossible and was never taught to me: that a Jew living under Nazi occupation could adopt a false identity and successfully live outside a Jewish ghetto posing as a Catholic Pole. Although extremely difficult, Reiss was able to successfully change his identity while never forgetting his Jewish lineage. Whereas the memories of Jews who used Aryan papers during the Holocaust have been seemingly forgotten about in other major sites of remembrance, this exhibit enables the thousands of Jews who changed their identities to be properly remembered. Not only does the exhibit demonstrate that not all Jews were hopelessly trapped during the Holocaust, but there are probably many other ways Jews were able to survive that have been similarly forgotten in the generalized narrative. This is what I found to be most meaningful from the exhibit, as being introduced to a new, forgotten understanding of past historical events that I thought I well understood was incredibly powerful and eye opening. It was also meaningful to learn what Henrk Reiss did to protect him and his family while remaining true to his origins.

Although Reiss could have maintained his and his family’s Jewish identity, this would have meant certain death. However, at the end of the war and given the choice to return home to Poland, Reiss decided the time was right to go elsewhere in order to remain with his Jewish lineage. For his two young daughters, who essentially knew nothing about their Jewish background due to living as the Darażs family for much of their lives, Reiss’s decision to reconnect with his real identity at the cost of his home allowed them to fully know who they were as Jews. Even though Reiss no longer lived in Poland, but in Australia, Reiss’s story shows how one could change one’s identity while remaining true to his Jewish heritage. In particular, although he no longer lived anywhere near Poland, Reiss was able to recreate a replica of the Oserdów garden he once had in Poland in his Australian backyard, preserving his pre-war identity living in Poland as well. Reiss’s story shows that not only is identity important in knowing who you are, but although difficult, it is possible for one to officially change their identity while remaining true to their lineage as Reiss did during and after the war.

Notes

- “Museum,” Galicia Jewish Museum, Accessed October 18, 2025, https://galiciajewishmuseum.org/en/museum/.

- “Henryk Reiss Must Cease to Exist,” Galicia Jewish Museum, Accessed November 6, 2025, https://galiciajewishmuseum.org/en/wystawy/henryk-reiss-must-cease-to-exist/.

- Henryk Reiss, The Engineers: A memoir of survival through WWII in Poland and Hungary, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam Publishers, 2024), 361.