These Walls Are Screaming: Graffiti in Central Europe

By Ian Eisenbrand

“Brick by brick, wall by wall, make the fortress EU fall,” at the Berlin Wall in Berlin, Germany. Photo by Ian Eisenbrand.

When moving through the streets and alleyways of Central Europe, you are constantly exposed to graffiti, with walls serving as a teeming public forum. Fragmented voices of anonymous protest cascade down cities’ walls in an almost overwhelming stream of political discourse. In my travels through Central Europe, I became fixated on the constrained anarchy of public discourse in the graffiti-riddled city walls of Slovakia, Czechia, Germany, and especially Poland. Compared to my experiences in the United States, graffiti in many Central European cities feels largely ungoverned. There is minimal evidence of efforts to remove defacement, with sprawling landscapes of expression seeming to build on top of one another before ever facing intervention. In the piling layers of graffiti, the constant display of flagrant right-wing, anti-establishment sentiments routinely inflaming into hate speech quickly caused my preoccupation to grow into an urgent sense of concern. When moving through the streets and alleyways of Central Europe, you are constantly exposed, even if passively, to these sentiments. Though it is possible to allow your eyes to graze loosely over these displays or to not look at them at all, their presence provides a unique opportunity to engage with fears and indignations often left calcified on the fringes of public discourse.

Elementary school mural altered into anti-US sentiment in Liberec, Czechia. Photo By Ian Eisenbrand.

The right-wing, anti-establishment graffiti across Central Europe looks to be prompted by a myriad of subjects, including anti-EU and USA sentiment, pro-Russia sentiments, hate speech against LGTBQ+ communities, and white nationalism. In their utilization of graffiti, the producers of these works convey the perspective of the uninvited, positioning themselves in direct opposition to the institutional infrastructures for democratic decision-making. While the outwardly hateful nature of some of these expressions negates their capacity to be welcomed in almost any other public forum, the existence of this graffiti reflects an unanswered crisis within the state of Central European democracy.

Some of the most politically charged pieces of graffiti in Central Europe are built on objections to the injustices committed by encroaching Western political forces. The European Union (EU) is often framed as a foremost perpetrator of this threat, a grievance typified in a clandestine inscription on the Berlin Wall stating, “brick by brick, wall by wall, make the fortress EU fall.” This expression does not promote the basis of resistance to Western political institutions commonly fostered by right-wing nationalists. Rather, it is a resounding mantra of protest to the EU’s escalating anti-immigration policies against the swelling numbers of migrants and refugees from Africa and the Middle East looking to enter member states of the EU in recent years (Frontex). Efforts to hold the European Union responsible for migrants and refugees from these regions are often grounded in the conviction the European Unions’ collective strength is partially built on member states’ historical intervention and economic exploitation in many refugees and migrants’ home countries, prompting the necessity of their migration.

In this, though, resistance to the EU’s interventionist policies is shared between clashing ends of the political spectrum, with Central European nationalists also framing their objections to the EU as a defiance of Western imperialism. The basis of this dissent diverges from the prior interpretation in its reliance on fears of sacrificing national sovereignty, both economically and ideologically, within the process of integrating into a supranational organization like the EU. Central European nationalists’ resistance to the European Union can be understood as a response to a perceived threat of exploitation within the EU’s transborder political infrastructures. These fears are also reinforced by the historical precedent of subjugation within Central Europe by larger international powers, especially in states like Poland, Czechia, and Slovakia.

Consumerism Killed God (NATO written over), Capitalism Killed Man, in Wrocław, Poland. Photo By Ian Eisenbrand.

As the hegemon within the West-centric global systems of power, the United States is another principal subject of graffiti centering on this fear. When walking through a suburban district of Liberec, Czechia, I discovered a striking expression of the grievances held against the United States in a defaced elementary school mural. The mural depicts a boat with the head of a dragon in a sea of blood, with an erupting volcano spewing flaming debris into the display’s foreground. The defacement of the mural transforms this school project into a vehement denunciation of the United States and its international influence. The word “USA-TAN” is a central inscription in the piece, equating the United States with the devil by fusing the USA and the word “Satan.” The coinciding inscription of the acronym “NATO” points fingers at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, an intergovernmental military alliance led by the United States. The stern of the ship is also marked “CIA,” the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency, an organization with a mixed reputation surrounding its intervention in international political affairs. The word “válka,” which means war in Czech, is also painted on the mural, framing the United States’ political warship as a world-shaking vessel. In the blurring distinction between the mural and its defacement, this apocalyptic scene is overflowing with unconcealed symbolic assertions of the United States and its political infrastructures’ fundamental guilt as an agent of war and destruction across the world. In this, the mural provides a point of entry into understanding the international context that informs the development of right-wing nationalism.

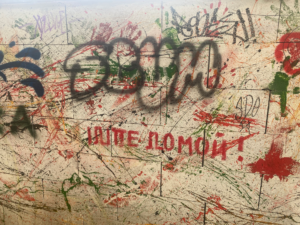

In these anti-EU and US sentiments, Russia often is framed as the counterweight, or axis, to the perceived imbalance within the international political system imposed by the West. In graffiti, this reveals itself in critiques of the autonomous state and people of Ukraine in relation to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This perspective understands Russia’s expansionist foreign policy as a viable opposition to Western hegemony, but often resents the influx of Ukrainian refugees into Central European countries due to the war. On the same wall as the anti-USA mural, the phrase “иди домой” is painted, meaning “go home,” in Russian. This phrase likely refers to refugees, or more specifically the 490,000 Ukrainians hosted by Czechia since the launch of the war (Jamet). The proximity of this graffiti to the mural criticizing the United States creates a thread of conversation, linking the Ukrainian refugee crisis with the larger proxy war between the United States and Russia. In the context of the attitudes surrounding the United States established by the mural, this graffiti expresses discontent over the refugees due to Ukraine’s association to the war-mongering United States. Graffiti of similar sentiments can also be found in Wrocław, Poland. however, a distinct historical subtext also roots pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian sentiment in Poland. In Wrocław, I encountered a sticker labelled with the acronym OWP, referring to the Camp of Great Poland, a historic far-right Polish political organization. This sticker refers to the UPA, a WWII-era Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary organization recruited by the Nazi SS during the Holocaust. At the end of WWII, the UPA also murdered 100,000 innocent Poles with the intentions of developing a homogenous Ukrainian nation in post-war reconstruction of state borders. Right-wing nationalists, such as the producers of this sticker, call back to this history in their critiques of the modern Ukrainian state. Through its merging of the UPA with the word Ukraina – the Polish spelling for Ukraine, the sticker conflates the two political forces, posing Ukraine as modern state run by Nazi collaborators, a stance promoted by Russia and Putin as a pretext for launching the war. The producers of this message see Ukraine as a longstanding threat to Poland and Poles, fueling resentment against refugees whose vitality has been drained by international forces far larger than them.

Across many sites, the Celtic cross, a “racist symbol of White Power,” was the most widespread images on city walls (‘Never Again’ Association). This sign, with deep roots in European history, has been appropriated by white nationalists. The traditional cross, a symbol of both Christianity and Irish pride, features “an elongated vertical axis (often accompanied by Celtic knotwork) that resembles that of other Christian crosses,” according to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). In contrast, the version used by white supremacists consists of “a square cross interlocking with or surrounded by a circle.” (ADL). Disturbingly, most Celtic crosses I witnessed within works of graffiti in Central Europe utilize the iteration of the symbol recast by white supremacists. The sheer quantity sprayed, stickered, and etched in city spaces across Central Europe is staggering. Wrocław’s city spaces are almost branded by the symbol, with the cross marking the city walls with unprecedented unity and an inescapable, viral quality. In its simplicity and symbolic quality, the cross stands in contrast to the rest of the graffiti I studied for this project, which are largely written texts holding more overt messaging. Although the roots of contemporary white supremacy in Central Europe are complex, the ideology does have significant associations with right-wing nationalism; in fact, many ruling parties with nationalist platforms in Central Europe have formed their base of supporters around varying degrees of white supremacy. For example, PiS (Law and Justice), the right-wing nationalist party that held majority rule from 2015 to 2023 in Poland, has an extensive history of fortifying white nationalism within its voter base. Through graffiti, the Celtic cross exists in these public spaces as a constant, howling call to the hate that underlines the formation of power by many right-wing nationalists in Central Europe.

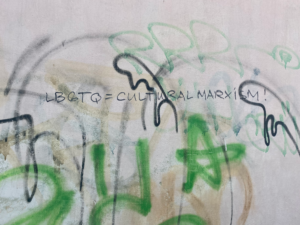

Although a less predominant trend, the presence of anti-LGBTQ+ graffiti illustrates a deeply entrenched foundation of right-wing ideology in Central Europe. Agnieszka Graff, a Polish writer and professor at the University of Warsaw, argues that much of the anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment in Central Europe is a ring-wing nationalist response to the EU-induced expansion of LGBTQ+ rights in the last two decades. Central European nationalists frame their opposition to the EU’s neoliberal social policies as anticolonial, with gender being imposed on the Central Europe as the last frontier of true Christian European values. The proliferation of the term ‘LGBT ideology’ as a political buzzword among conservatives in Central Europe frames LGBTQ+ movements as driven by an ideology rather than by a community of shared identity. In this, the producers of this graffiti understand sexuality and gender as an ideological reinforcement of Western hegemony and the eradication of their national values (Graff). This perspective and the graffiti professing its values cast the sexuality and gender of fellow citizens, including those who may pass by these works, as perpetrators of ideological imperialism.

The forces that prompt the creation of this graffiti are not a beast best left as an abstraction within our democratic decision-making. Rather, these displays exist because of an exigent demand for an agora willing to house these perspectives. This graffiti is not meant to pacify the violence boiling under the heat of anger that emanates from these walls. Rather, it illustrates the latent threat of what the producers of these works would likely believe to be just retaliation. This threat extends not only to the systems these groups resent, but also to innocent citizens, scapegoats in this ideological conflict, such as the LGBTQ+ community. In the interest of solutions, it is crucial to recognize that graffiti of this nature exists as a symptom of a perceived insufficiency of systemic recognition. What then becomes incredibly difficult is separating the unacceptable nature of their delivery and the glaring need for these grievances to be addressed and challenged in an institutional, democratic forum. These walls are screaming, yet there does not appear to be a present capacity to offer them a response.

Works Cited

- Celtic Cross. Anti-Defamation League. https://www.adl.org/resources/hate-symbol/celtic-cross

- Frontex: EU Border Control in Africa Set to Expand, Commission Floats Political Oversight, Switzerland to Vote on Frontex Funding, Belgium Plans Scrutiny Hearing. European Council on Refugees and Exiles, 2022. https://ecre.org/frontex-eu-border-control-in- africa-set-to-expand-commission-floats-political-oversight-switzerland-to-vote-on- frontex-funding-belgium-plans-scrutiny-hearing/

- Graff, Agnieszka. Global Anti-Gender Movement and Right Wing Populism. 2023.

- Jamet, Marie. War in Ukraine: which European countries host the most refugees? euronews, 2023. https://www.euronews.com/2023/09/20/war-in-ukraine-which-european-countries- host-the-most- refugees#:~:text=In%20absolute%20numbers%2C%20Poland%20(1.5,Ukraine%20according%20to%20UNHCR%20figures.

- “Never Again” Association. “LET’S KICK RACISM OUT OF STADIUMS” CAMPAIGN “Never Again” Assocation, 2009.