Jarocin: A Beacon of Hope Where Hopelessness Reigns

By Winter Cameron

“We created our freedom within. That’s the best thing about it. It was like they did in prisoner-of-war camps, where they held Olympic games, sporting competitions, poetry recitals and had theatres performing, while they knew they did all of that behind the barbed wire. Yet, doing it all they felt free. That’s why they did it. To feel good.” – Krzysztof Grabaż Grabowski (Jarocin. Po co wolność, 0:23:23-0:23:54).

From the underground fighters resisting the Nazi occupation, to workers protesting communist rule, 20th century Poland has a rich history of the formation of opposition groups. Solidarity is likely the most famous movement of the modern era, which started as a worker protest in the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk. What started as a humble workers strike then turned into a full-blown anti- Communist independent labor union: a unique, and unheard-of thing in the Soviet bloc. Solidarity then developed into almost a Socio-Cultural movement that became a large part of Polish society and identity throughout the 1980s. Solidarity became a symbol of hope against the oppressive regime in the People’s Republic of Poland and acted as a catalyst for many different anti-establishment initiatives in popular culture in Poland.

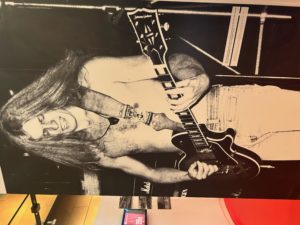

The history of Solidarity is told in detail at the European Centre for Solidarity in Gdansk, from the initial Shipyard strikes to the spread of the trade union throughout the country, to the negotiations that the trade union lead with the government in 1980 and 1989. The museum also explores the role of the church in the anti-communist movement. At the time of Solidarity, a “free” underground press and political cartoons flourished that gave voice to those who protested the government. However, there was one part of this history in the exhibition that really caught my eye, and that was the focus on underground art movements, especially the section on a major rock music festival of the 1980s held in Jarocin.

I have always loved learning about alternative music scenes, whether it be the origins of the Goth music scene in England, the Emotional Hardcore scene of DC or the DIY Hardcore Punk scenes across the globe. Each scene always acts as a countercultural response to whatever seems to be ailing the world at a given moment. By giving voice to complaints towards the current popular culture, these scenes provide solace and community to the disenfranchised, or to those who feel scorned by the ruling authorities. The thing I admire specifically about alternative scenes was the fact that so many of them were based on DIY principles. If someone had a guitar, a cheap amp and a dream, you could make a band. DIY scenes give any person access to the ability to create music, no matter their talent, and to have their voice heard and appreciated. It did not matter how clean anything sounded, in fact, the rougher the sound, the better. The same pertained to appearances: the dirtier and the stranger the look, the better. These principles were very present in the Jarocin festival.

Jarocin was a DIY festival: it started out as a grassroots music festival in a battle-of-the-bands style of competition, where the audience, rather than a jury, voted on the best bands. At the start, most bands were playing softer, jazzier or poppier genres: something more palatable for general audiences. However, a demographic in the 1980s and the political atmosphere led to a shift in the music performed at the festival. With the collapse of the Solidarity movement, and the subsequent imposition of Martial Law, younger people started to feel a sense of hopelessness; they favored a harsher, punkier and alternative style of music to represent them. Despite punk rock being illegal under Martial Law, many police would turn a blind eye to the festival and would allow the festival to run. This meant that Jarocin provided an escape from the hopeless, disappointing reality that was Communist Poland. The annual festival offered freedom from censorship and allowed a free space for artists and their audiences to explore ideas without fear of censorship. Even when songs were censored, it was very loose in comparison to other forms of media. So Jarocin, as Grzegorz Piotrowski notes, was about exploring new genres of music and getting way from society: “On the one hand, as most of the rock music, it was a form of search for freedom, but this time understood in a different way. At the core of this freedom was autonomy. Young people in 1980s were looking for autonomy from the everyday life but also from politics. Criticisms were made towards the regime but also towards the pro-democratic dissidents, whose program began to diverge from the needs of the young generation. (Piotrowski).”

A parallel exists between the DIY Hardcore Punk scene around the world and in Poland. Most DIY punk scenes rely on the community to put on shows, whether it be at house/basements, or at buildings that will happen to host people. Continually, the community helps make the festival: whether it be by contributing a space for bands to play, or by providing food, or a place to stay for the audiences. This was true for Jarocin: the festival was not an official government event, so the community surrounding Jarocin all contributed to help the festival run smoothly. The residents of Jarocin invited people to live in their homes, so, like global DIY music scenes, a community was created between audiences and the town of Jarocin around the event and the music. Additionally, another similarity between these two scenes are the sounds: since rock/punk music was illegal under Communist rule, the bands had to provide their own equipment and thus had a more raw, real sound that resonated with the audiences of the festival. This rawness in turn was what drew young people into the festival, the sound accurately reflecting their frustrations.

What was distinct, then, was that Jarocin was made by the youth and for the youth. Semi-autonomous institutions such as the Catholic Church and their rigid beliefs did not capture the rebellious attitudes of the youth. Even the dissident groups opposing communist rule did not effectively attract those that were uninterested in political movements, or those who wanted to rebel against the oppressive social order of Polish society. The strict and rigid values of Poland’s Catholic Church at the time tended to push away those who sought more extreme forms of personal expression; many pro-democracy groups did not tend to appeal to the needs of those who just wanted a break from politics and the bleakness of day-to-day life.

Jarocin acted as an outlet for the frustrations these young people felt. As for many youths behind the Iron Curtain, the 1980s was a time of hopelessness and uncertainness. Unlike the youths in the West who were experiencing prosperity and economic boom, the bright future and opportunities they had were not promised Iron Curtain. So, the bands playing at Jarocin gave a voice for the hopeless. Interestingly, compared to most punk bands which usually speak of open rebellion and a hope for a better future, it became very popular to relay the opposite to further reflect the sentiments of the average person in Poland. “The punk slogan “No Future” was so powerful in communist Poland because for most of the young people it was very real. The autonomy was a retreat into a world of fantasies, a parallel system drastically different from the reality,” noted scholar Grzegorz Piotrowski. Jarocin provided a space and a voice for the average person to admit their hopelessness and frustration from the system, and that there was indeed “no future” for them at the time—something they could not admit openly under the PRL.

A difference of Jarocin compared to the other forms of protest in Poland was that it wasn’t just a protest of the political and ideological based oppression that the people faced under the PRL, but it continued to be a protest of the rigid societal structures of society. “The rebellion of youth at Jarocin was not explicitly political. It was more against the social system and the lack of perspectives for them. The rebellion in terms of lyrics but also in terms of the artistic language used to express it was against more structured emanations of the regime’s power. (Piotrowski).” In that regard, Jarocin then reflected the discontents within the society and the lived realities of the youth of Poland. It was not just the lack of expressed freedoms that were the main driving forces for Jarocin; the driving force for the success of the musical festival was the fact that it ended up being a safe space for participants – the artists and the audience — to be able to express themselves freely without having to follow the rigid and strict social culture enforced in the communist period.

Works Cited

- Piotrowski, Grzegorz. “Jarocin: A Free Enclave behind the Iron Curtain.” East Central Europe (Pittsburgh), vol. 38, no. 2–3, 2011, pp. 291–306, https://doi.org/10.1163/187633011X597216.

- Jarocin. Po co wolność, Directed by Marek Gajczak and Leszek Gnoinski, Barton Film, 2016.