Exploring the Bavarian Quarter- How Lessons of Memory are Passed Through Art

By Nicholas Wilkerson

During our trip to Berlin, we visited what was a major Jewish neighborhood in Berlin prior to the Second World War, known as the Bavarian Quarter, where famous Germans of the Jewish faith such as Hannah Arendt and Albert Einstein once lived during the days of the Weimar Republic. The Bavarian Quarter was an upscale neighborhood, referred to as “Jewish Switzerland” prior to the rise of Nazism. While German Jews could live anywhere, many chose to settle in this comfortable, fashionable neighborhood, with parks, greenery and fashionable, high-quality apartment buildings. While religious and social equality between all German citizens was law before the rise of Nazism, it is important to know how the early days of Hitler’s reign impacted Jewish people living in Germany before deportations or the Final Solution began. After the Nazis’ rise, the Bavarian Quarter’s residents were impacted by laws that gradually disenfranchised German Jews, separating them from German society. The first laws gutted the German civil service, paving the way for further dehumanization and legal discrimination against the Jewish population.

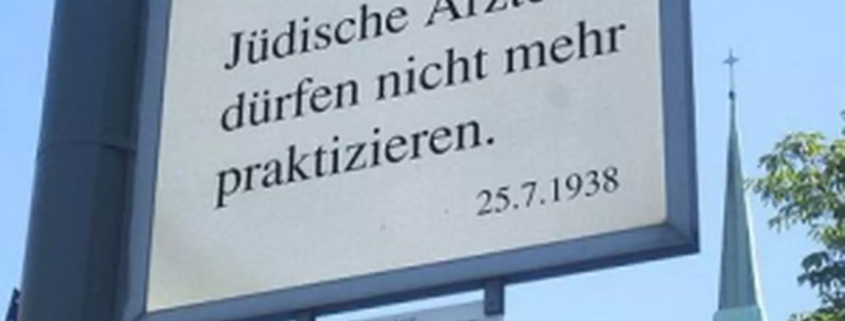

Today, the Bavarian Quarter is a place where these laws can be studied in detail, due to a large artistic installations titled “Places of Remembrance”, opened in 1993 by Renata Stih and Freider Schnock. Anyone exploring the Bavarian Quarter near Haberland-Strasse today (named for influential Jewish land developer Georg Haberland), could see the elements of this memorial to the Jewish experience in Berlin during the entirety of Nazi rule. The art installation takes the form of signs hanging off lampposts, visible to any passersby. On the one side, the signs show an image, on the other, a fragment of an anti-Jewish law of the Nazi era. These signs, eighty in all, can be found all through the neighborhood. The choice to scatter these signs ensured the memorial accomplished what a centralized installation could not; it conveyed the idea that no matter where Jews all over Germany turned, they were constantly reminded of the gradual stripping away of their identities and rights through the legal system. This choice was logical on the artists’ part; a centralized monument would fall short when depicting this aspect of history, not evoking the suffocating, surrounding feelings this installation does. The introductions of laws targeting Jews and other minorities were part of a a slow, immovable process that turned Jewish citizens’ world upside down. They were no longer citizens of a religiously tolerant German Empire or Weimar Republic.

Each sign represents a different anti-Jewish law passed by the government. Legal anti-Semitism began gradually leading up to the Second World War, with laws that targeted Jewish people in an arbitrary way, such as not being allowed to buy cake, sing in choir groups, or help with community gardens. These laws, despite their seeming arbitrariness, were an exclusionary prelude to the horrific fate all Jews remaining in Germany would face. Specifically, the established and culturally assimilated pre-war Jewish population was dehumanized and separated from German society not only through propaganda, but as the Bavarian Quarter installation outlines through legislation. Following one of the first laws (Law for the Restoration of the Professional and Legal Services), Jews were gradually purged from being lawyers or judges. This gradual process of legal discrimination was the first step towards deportation, and eventually led to the implementation of the Final Solution.

The rules resulting from these evolving laws, once put in place by the Nazi government, were often posted in public spaces, much like the art installations displayed today, likely a conscious choice on behalf of the artists. Some of the signs also include personal testimonies, such as one of a non-Jewish woman recounting her husband being killed by the Gestapo for keeping a canary at home, following a total ban on Jews owning pets. While the seeming superfluousness of some of the laws that touch on details of daily life such as commuting to work, buying groceries, or keeping pets, this testimonial shows the laws’ horrific consequences, such as the draconian punishments exacted upon Jews for breaking these laws. To today’s observer, this cruelty was a step beyond even dehumanization, which was the clear intent of the Nazis, intending to humiliate and “other” Jews in such a strong way. As a result, many average Germans witnessed and accepted this two-tiered society exacted on their neighbors, supporting their government in carrying the laws out.

What adds to the insidious nature of these laws was a practice seen at the Nazi Party’s inception. In the year 1936, when Nazi Germany hosted the Olympics, the signposts were changed to contain much more neutral language (e.g. “Jews are not wanted here”), to ensure visiting foreigners would not know of their true actions. This element of secrecy practiced by the Nazis persisted right until the end. The last chronological signpost dictated in February of 1945 that all records of pre-war antisemitic laws should be destroyed. By this point, it was clear that Nazi Germany would lose the war, and this was obviously an attempt to hastily cover any evidence that the Nazis started their terror by targeting Jews in particular. However, this failed, and the Nazis’ crimes were exposed to the entire world.

Stih and Schnock’s installation was introduced in a newly reunified Germany, illustrating the importance the memory around the Holocaust was to play in the period after 1989, where something this horrific could never be allowed happen in the new Germany. However, some of the responses to the memorial depict a myriad of attitudes to these efforts. Some disapproving Berlin residents opposed the efforts to memorialize the antisemitic laws and the Jews they targeted. During an interview with the New York Review of Books, Schnock himself outlined one such reaction, where one unnamed resident called the workers hanging the signs “Jewish pigs” and told them to leave the neighborhood. Such language would not be out of place when the laws were in effect under Nazi rule. On the other hand, some took the signs at face value and believed them to be a malicious attempt to resurrect a dark past that should not be remembered. These individuals notified local authorities to report what they considered antisemitic vandalism. These examples prove that disregard for history or memory have the potential to cause hatred and ignorance much like that which led to genocide. The only way to avoid a repetition of this past history is to remember these events, even if they are inconvenient truths that some would prefer to forget or hide. However, these signs are more than just a reminder of a dark time, they are a warning that a nation should not disregard any of its history.

Works Cited

- Johnson, Ian. “‘Jews Aren’t Allowed to Use Phones’: Berlin’s Most Unsettling Memorial,” New York Review of Books (Blog), June 15, 2013.