Overshadowing Holocaust Remembrance in Central Europe

By Taylor Krzeminski

In Central Europe, memorialization of lost life during and after the Third Reich rarely centers on how to remember, but who is worth remembering. Places of remembrance often engage in rewriting history – distancing citizens from complicity under fascist and communist parties as times of ‘foreign occupation’. Besides small acknowledgements of the impact of national socialism and the Holocaust on minority communities in Central Europe, there are gaping holes within the memorial scene. When viewing monuments and museum in Budapest and Prague, I found myself reflecting on the refusal to be accountable – the horrors of the Holocaust were painted as part of Nazi occupation, not citizen complicity. This victimization allows current right-wing governments across Central Europe to create a narrative that distances their own politics from the politics of totalitarianism.

This silencing of the past that happens in the process of focusing on the nation as a victim of Nazi occupation is evident at the former labor camp for Roma located at Lety in today’s Czech Republic. This internment facility was established by the Czechoslovak government as a labor camp for those who were deemed asocial. Throughout the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, Lety was changed to a camp for Roma and Sinti, often referred to as “gypsies”. In 1943, the approximate 500 inmates of Lety were deported to Auschwitz. Before the deportation, about 300 had already lost their lives to disease and living conditions. While about 800 people from Lety died, either at the camp or at Auschwitz, a majority of the Roma who lived on the territory of today’s Czech Republic before WII were murdered during the Nazi period. The majority of the Roma who live in Czech Republic today had come from the Slovak lands and settled here post-World War II.

Compared to the staggering 11 million deaths associated with the Holocaust, the victims of Lety quietly disappear into the background. Especially in a society that portrays victims of the Third Reich as all, or at best Jewish, the Roma suffering is able to remain forgotten with little resistance. Lety was an asocial camp – designed to imprison those who ‘avoided’ work or lived in poverty. This stereotype of Romani people prevails today, also complicating their ability to memorialize their history during World War II.

After the war, the grounds were converted into a pig farm from 1971 until 2017. Pushback to commemorate the camp began in 1995, and the pig farm was finally bought by the Czech government in 2017. In recent years, a small exhibition was erected to describe the history of the labor camp. All of the information, though, is in Czech besides two posters in German and English. This is incredibly inaccessible to tourists, and minorities that do not speak one of the three languages within the exhibition. While it is important to teach citizens of the country their history, it is a roadblock for Romani who may not speak the language due to education segregation or for cultural reasons. Keeping history limited in such ways does not allow those of a persecuted community to learn about a part of themselves. A five-minute walk away from the exhibition stands a small tower of rocks, which serve as a memorial to the victims of Lety. The inscription on the rocks, as well as the monument itself, is hard to notice in the middle of the forest. While our group observed the memorial, several people hiking glanced at the rocks. Unless one was aware of the history of this park, the monument appears to be just scattered rocks, and could be mistaken for natural features in the environment. During our visit to Lety, several people in our own group continued to talk, make inappropriate jokes and ignore our tour guide. If administrations do not respect persecuted communities, the general public will not respect them either.

The question of who is worth remembering also arises in Budapest, at the House of Terror. This museum is designed to focus on the terror that occurred under the fascist Arrow Cross Party at the end of World War II and the Soviet-backed secret police, State Protection Authority (AVH).

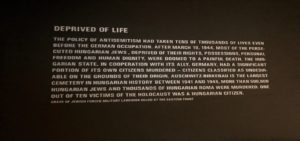

Before stepping into the museum, this may seem like a balanced approach to dealing with the country’s past. Funded under the government of Victor Orban and the populist Fidesz Party, the four floor museum features only four rooms about the occupation of Hungary by the Nazis in 1944. While the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany had grave impacts on the Jewish community living there, antisemitism was present in Hungary well before 1944. Anti-Jewish legislation was introduced in 1938, before Hungary had officially joined the axis powers in 1940. These laws reversed equal citizenship and restricted the personal and public lives of Hungarian Jews. Forced labor service was required by the “politically unreliable” and Jewish men beginning in 1939. With Jews being banned from serving in the military during World War II, the alternative was mandatory forced labor. While mass deportations of the Jewish-Hungarian population did not begin until Nazi occupation, Hungarian authorities did deport Jews several times, for example in 1941 when 20,000 Jews were deported to German-occupied Ukraine. Omission of Jewish deportation and extermination overshadows the fact that they were targeted victims of the Nazi ideology. Occupation was only one aspect of how National Socialism impacted the Jewish community of Hungary.

Having seen the Budapest Holocaust Memorial Center before House of Terror, I was shocked at the blatant disregard for Hungarian participation in anti-Semitism and racism. The duty of this museum should be to factually honor victims of Nazi terror, regardless if there is a Holocaust museum in Budapest. Not only did the museum ignore a large chunk of Hungarian participation in Nazism, it also trivialized the Jewish experience. With intense music, the sound of splashing water and abstract artwork, it took away from the history and turned terror into commodified entertainment for tourists. The House of Terror, like the Lety exhibition, does not have language translation. While tours are offered in English, the tour guides rarely go into detail about atrocities and do not explain the Hungarian information throughout the rooms. Not only does this museum determine communist victims are moreimportant, it also determines who will have access to the written history within the museum.

It is critical for countries in Central-Eastern Europe to reflect upon and analyze the complexity of public and private life during the reign of totalitarian regimes. However, prioritizing communist suffering over the Holocaust has become a political tool for right-wing parties to say: here is who is more important. In this statement they contradict themselves; it is easier to say everyone suffered under communism than it is to keep their narrative that we all suffered under the Third Reich. In instances where memorialization of victims of the Holocaust is inclusive, accessible and acknowledges citizen involvement, then we can perhaps say “enough”. Both could even be done simultaneously – however it seems these governments want to pour resources into rewriting history, or into anti-communist remembrance. As a visitor at several of these memorials designed to paint terror as imposed by foreign invaders, I felt both scared and grateful. Grateful that my access to education allows me to think critically about how memorial work can strip marginalized communities of their history and suffering. Scared, that many people will see these memorials, ignore them or believe them. While the push back on Holocaust remembrance in Central Europe is not outright denial of the Holocaust, it does eerily mirror the fascist past they have yet to come to terms with.