The East Side Gallery: Forum and Monument

By Michael Kosowski

To recall the first time that I, to use a colloquialism, stepped up on my soapbox, is rather hard to do. There is no one event, no specific time that marks my morphing into an individual who constantly expressed his beliefs and voiced his concerns. To put it bluntly, speaking my mind has come as naturally as taking a breath. The world has been my soapbox, anyone finding themselves in my company has been my audience, and almost every space from a subway car to a park has been my theatre. I can say that I have been very lucky to live in a country where freedom of speech has been ensured for over two hundred years. I was never so grateful for this fact or really ever conscious of it, however, until I visited Berlin. In this article, I am going to illustrate how my visit to Berlin’s East Side Gallery forced me to ponder the liberties I have been awarded since birth. Furthermore, I will examine the East Side Gallery in the light of what philosopher Hannah Arendt called a “Space of Appearance.” Through this, I will explain how I think the East Side Gallery served as a crucial site for forum making in a post-Communist unified Germany.

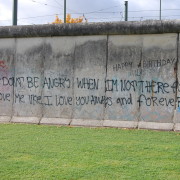

Upon arriving at the East Side Gallery, I was confronted with approximately a mile of unwinding wall before me. It seemed like a string that had dropped to the floor, waiting for me to ravel it back up again. The wall twisted, turned, curved and wiggled, causing me to feel the necessity to constantly move from one panel to the next. The Gallery is outdoors and runs adjacent to the Spree River, consisting of murals painted on the Berlin Wall. The site appeared very harrowing to me, especially when I remembered that what is now an artistic venue was once a site of patrolled surveillance and possibly death. The wall was severed in some places, allowing for the opportunity for visitors to approach the river. An action seemingly easy for me would have been impossible only thirty years ago.

Speaking one’s mind, like walking in and out of the voids in the Berlin Wall, is another action that seems only natural today yet impossible thirty years ago. Before I arrived in Berlin, I watched a film entitled The Lives of Others, which depicted the practices of surveillance in the former German Democratic Republic. Characters were unable to speak even within their own home. Secret police would record their every move, and claim that it was for the protection of the state. These policies forced the public to have no space to convene, to argue, or to create a forum for discussion. The only “space” from with “truth” may radiate is the government. Thus, coffee houses, billboards, televisions and radio stations were not places to express belief or opinion, but were rather places to laud the government and present their propaganda.

Walking along the East Side Gallery, a friend expressed her regret that a panel was covered with graffiti. I, too, felt that the graffiti ruined a work of art that otherwise would have been pure and beautiful. I thought nothing of the graffiti until I came across another panel that had a message spray-painted on the bottom. The message read, “Free Palestine From Hamas.” Suddenly, it dawned on me: this gallery repurposed the Berlin wall to be a monument to the freedom of speech. The spray paint, rather than being unnecessary graffiti, was something that inevitably accompanied the art celebrating the history of the city.

But how can I argue that the spray paint needed to be there? How can I make an argument in defense of the graffiti? Well, this argument is rather one based on emotion. I recalled how commonplace it is to speak one’s mind in America, and how such monument-making was never expected to capture the freedom of speech. In Berlin, however, the Wall seems to beg for commentary. It is a vestige, a remnant of a time of denial of individuality, avoidance of logic, and prevention of debates on “truth.” This structure, the Wall, seemed to be retained in order to allow for the inhabitants of Berlin to not only express themselves, but also seize an opportunity that is roughly twenty five years old. Both the United States and the lands that are now considered Germany were once hosts to the Enlightenment, where notions of such freedoms were born. Perhaps the Wall is a celebration for a re-acquiring of a very European idea. Perhaps the Wall continues to memorialize itself by allowing members of the international community to use it as a space to create a forum of ideas.

Hannah Arendt argued that democracy depends on the existence “spaces of appearances,” where individuals can voice their opinions. The spoken word is inextricably tied to action. In her book The Human Condition, Arendt argues that these spaces are contingent on action; they rely on people coming together and acting in the public domain. Thus, rallying, painting, drawing, talking, and discussing: all of these are examples such practices. This action, however, could be taken one step further. I walked along Berlin’s East Side Gallery, I pondered the messages of the murals, I discussed the meaning of the graffiti with a friend. Because the East Side Gallery forces you to act, and perhaps react to the actions of others, it becomes a milieu in which the barriers between word and action disappear. The borders between doing and thinking become hazy, and the visitor is forced to reassess so many beliefs and understandings that he or she arrived with.