The Berlin Wall: More than Just a Physical Partition

By Madison Bollart

For the past couple of months I had been looking forward to our trip to Berlin. However, this would not be my first time in the city. A few years ago I visited on my own, not with any intention other than to be a tourist. I had booked the trip knowing very little about Berlin or its history. I understood that the Berlin Wall had historical significance, but other than my knowledge of this place was limited. What I did know was that I wanted to go to the East Side Gallery and snap some pictures to post on my Instagram account. So I did, blankly walking down the sidewalk taking pictures of the brightly painted murals that caught my attention, for no reason other than that they were aesthetically pleasing. I spent the rest of the weekend aimlessly wandering around the city, and then caught the next flight home.

Two years later, I have learned, read, and traveled so much. This time, I was so excited to come to Berlin, a place I have been taught so much about. It was the capital of 5 different Germanys; Kaiserreich (The German Empire) from 1871 to 1918, the Weimer Republic from 1918 to 1933, the Nazi Regime 1933 to 1945, East Germany from 1949 to 1989, and the Reunited Federal Republic of Germany from 1990 to today. Berlin has long served as the epicenter of Central European rule, conflicts, and wars with devastating consequences. Today, Berlin is the capital of a democratic Germany within the European Union, therefore bound to numerous checks and balances by international conventions and its own constitution.

Being able to experience the city on the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin was incredible. Public spaces were vividly decorated, stages were assembled for celebratory demonstrations and overall, I could feel a general sense of collective joy and exuberance. The anniversary is one which would celebrate the fall of the Iron Curtain, a pivotal event that would mark the end of an ideologically divided Germany. The world was shocked at the crumbling of the former East German communist dictatorship.

Following its defeat in World War II, Germany was split up amongst the former Ally Powers. The United States, France, and the United Kingdom agreed to unify their pieces of occupied Germany and occupied Berlin into one, which would form the Federal Republic of Germany. East Germany or what would later be referred to as the “German Democratic Republic” was founded on October 7, 1949 and was occupied by the Soviet Union. Given that Berlin is geographically situated in the east, it was divided between east and west in order for the GDR to maintain the city as its capital. This split would serve as a more than just physically divided zone, but also as the face of an ideologically divided world. The Berlin Wall, built by the East German government, was constructed with an aim to maintain a functioning communist state and to prevent its people from escaping to the West. It would come to stand as the symbol of a eastern communist dictatorship being isolated from the democratic and capitalist western world. For nearly 40 years, The German Democratic Republic would be a state maintaining strict travel bans, restriction of free speech, an insufficient command economy, and an invasive surveillance network operated through the Stasi, the East German secret police. It was the “shield and sword” of the SED, the Socialist Unity Party which formed the political elite and governed the GDR. The Stasi was one of the most aggressive secret services in the Eastern bloc countries and built on psychological repression of its citizens through a wide network of informants resulting in thousands of files containing detailed, personal information that could be used to blackmail and silence political dissidents.

By 1989, East Germany was one of several states in the Easter Bloc whose citizens would be taking part in revolutions and peaceful protests opting for moves toward reform and democracy. On November 9, 1989 the East German government announced an easing of travel restrictions to the west at a press conference by what is often thought of by accident. When asked when the policy would begin to utter surprise the response was “immediately” and so caused the mass movement of people to cross the wall to the west that evening. The border guards were at first confused, but let the people through to the west, and celebrations commenced in Berlin. This would in many ways mark history, paving the way for future progress internationally.

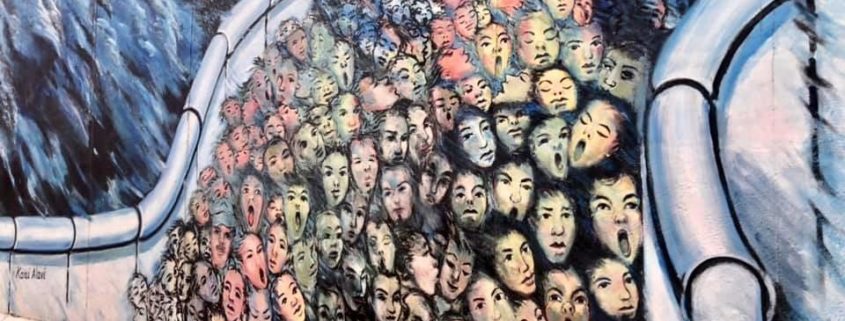

This of course, is an incredible reason to celebrate; 30 years ago and still today, this event stands as a symbol of a long awaited modern freedom. It was something that was hoped for by many, but an event no one could confidently denote a time or date to. The element of surprise however, allowed for a wide array of different emotions— many joyous, but also many upset, confused, distressed. This idea of mixed emotions over an event normally associated with celebration was illustrated to me when I visited the East Side Gallery for the second time. I came across a mural titled ‘Es Geschah im November‘ or ‘It Happened in November’ by German-Iranian painter Kani Alavi. I then understood that this work was inspired by how the artist personally recounted the fall of the Berlin Wall from the windows of his apartment overseeing Checkpoint Charlie. He watched thousands pour through the border, one which previously distinguished the Soviet and American sectors. The mural portrays a sea of faces rushing through what was once considered “no man’s land.” It is rather chaotic, and the numerous faces exhibit emotions of shock, distress, and even displeasure. This introduced me to the idea that an event popularly associated with exuberance, both in the past and in the present, realistically evoked emotions that were many times not celebratory, but instead filled with uncertainty and fear of the future. The mural in many ways figuratively uses this idea of “no man’s land” as a space of confusion; a gray area of emotion about the past and movement into the future. While ‘It Happened in November’ is a depiction of the emotions of what has happened in the past, we can understand that these feelings may still resonate in the present more often than what may be seen on the surface. The anniversary of the fall of the wall may evoke these same emotions felt by Berliners on the that day in 1989.

I still wondered how East Germany, a place often negatively connotated with communism and authoritarianism, could be mourned over by its own people who fell as victims to such oppression. It was really only until our guide who is from East Berlin, recounted the city as what she considered a community and her home, “no one left and no one really came.” I started to understand that these feelings of nostalgia of the past may have induced the mix of emotions exhibited at the initial fall of the wall. East Germany was a dictatorship, but it was also a place where people worked, raised families, and lived their everyday lives. Even if life was not considered the best in the East, it was what people were used to— for many it was all that they knew.

‘Es Geschah im November‘ or ‘It Happened in November’ by German-Iranian painter Kani Alavi at the East Side Gallery

I began to see this fear and uncertainty as a theme of what would follow 1989. I read an article by Sławomir Sierakowski, who was 10 years old and living in Poland when the wall fell. He highlighted that while there was initially great feelings of excitement, there also was the very opposite, “It was very safe in our police state. We didn’t have competition, or the accompanying stress. There was no rat race. And while that was a source of backwardness, it was also a major advantage that disappeared after 1989. Longing for that old state of things has caused long-lasting, not always irrational nostalgia for communism” (2019). This represents that even today, this longing of the past still remains, even if it is regarded as a historically negative period. This idea of nostalgia of the communist past individualizes those who lived behind the Iron Curtain— it exhibits the reality and variation in human emotion of those who lived under Soviet influence.

A couple of months ago I read the book The Wall Jumper by Peter Schneider. It is a collection of different stories told from the perspectives of people who lived on both sides of the Berlin Wall. One quote in particular stood out to me, “It will take us longer to tear down the Wall in our heads than any wrecking company will need for the Wall we can see” (2005). Remembering this now has helped me understand that the Berlin Wall stood as much more than a physical partition. It even represents more than what was an ideologically divided world. We can understand that with the fall of the Berlin Wall there is no longer a structural divide, but the difficulty of individual mental division is still ever present. This emotional barrier remains far longer than the physical barrier has. It is possible to feel negative emotions, positive emotions, and more often than not, both. Individuals are still learning to understand and come to terms with life behind the wall and in turn, how to move forward with this lurking presence of nostalgia.

The Berlin Wall no longer serves as just a trendy photo-op for my Instagram. I can understand it as a piece which is representative of a confusing collective memory. While for many, the 30th anniversary of the fall of the wall serves as a celebratory event of freedom, for others it resurfaces the confusing emotions felt three decades ago. The nostalgic feelings of comfort, security, and memory conflict with the scars of authoritarian oppression behind the Iron Curtain. The Berlin Wall no longer physically divides East Germany from the West, however it emotionally divides individuals from one another. One person’s celebration can be another’s yearning of the past.

Sources

Schneider, Peter. The Wall Jumper. Penguin, 2005.

Sierakowski, Sławomir. “I Was 10 When Communism Fell in Poland. My World Became

Colourful – but Unstable.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 4 June 2019,

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jun/04/communism-poland-democracy-pepsi.