Resisting Fear: The Ringelblum Archive

By Kate Christie

Resistance can take many forms. It can be physical, meaning to uproot given oppressive institutions through explicit verbal or armed struggle. But what about spiritual resistance; a form of resistance–while less explicit, but just as crucial? Holocaust survivor, researcher and activist Rachel Kostanian Danzig, defines spiritual resistance as:

“any intellectual activity of an individual or a group, undertaken consciously (or subconsciously) to help other people and themselves to overcome the physical and moral terror imposed on the Jews by the Nazis. While ‘spiritual’ usually refers to faith and religious values, it can also mean highest abilities, higher moral and intellectual qualities.” (p. 21).

I would argue that the curation of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto constitutes a mode of spiritual resistance under Nazi Occupation in accordance.

Columns installed at “An Archive More Important than Life”, an exhibit at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish History Museum. Columns represents stacks of archival materials; at the base of each column, materials can be viewed on a touch-screen

The Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, also known as the Ringelblum Archive, is a collection of preserved documents and materials. These documents reveal diverse accounts of onslaughts on Jewish life during World War II and under Nazi Occupation. The archive is named for one of its founders, Emmanuel Ringelblum, who was a historian, high school teacher, and social activist. He co-founded the Jewish Social Self-Help, a Jewish mutual-aid organization tolerated by the Nazis, in the Warsaw Ghetto. Co-founding the Jewish Social Self-Help allowed him a means to pursue covert individual and, later, collaborative archival work of Jewish repressions. Ringelblum organized the founding meeting of the Oneg Shabbat (“Joy of Sabbath”) in 1940, which would become an underground research institute in the Warsaw Ghetto. Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat’s initial archival work focused on Jewish subjugation. For instance, Oneg Shabbat relied on ordinary people to document, and preserve documentation, of their everyday lives in the ghetto: the good, the bad, the ugly. While many contributed personal journal entries, others contributed artefacts too; those included newspapers, ration tickets, letters and postcards, German orders, invitations to events organized in the ghetto, leaflets, theatre posters, school assignments, tram tickets, candy wrappers, photographs, original artwork, and poetry. Later archival work focused on Jewish extermination—via massive deportation efforts to labor- and death-camps—under Nazi occupation. Oneg Shabbat continued archiving even after the Great Deportation in 1942, and only stopped shortly before the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The Ringelblum Archives were buried in August 1942, at the height of the Great Deportation. They remained buried until September 1946, after the end of World War II. Almost 30,000 documents from the Archive, written in Yiddish, Polish, German, and Hebrew, have been recovered since (Jewish Historical Institute).

While almost all members of the Oneg Shabbat didn’t survive the war, they live on through the Archive. The Archive reveals that many, along with those ordinary peoples that they collaborated with, were involved with not only social activism, but education, literature, history, and economics. Some are profiled below:

- Izrael Lichtensztajn was a teacher and pre-war editorial assistant at a literary weekly. The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute relays that “for the Archive, he documented underground education in the ghetto, in which he himself was involved. He co-ran the school in the basement of which the Archive [was] hidden”.

- Henryka Lazowertowna was a poet and activist. She wrote a history of the ghetto’s refugees; her writing references Self-Help statistics to trace the stories of individual families and describe their struggles to survive in the ghetto (The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute).

- Nusen Koninski authored “The Image of the Jewish Child”, a book outlining conditions of children—whether street, refugee and fugitive, etc.—during othe war, considering factors such as juvenile criminality, private education, and the work of welfare agencies. Koninski, himself, was one of the most mysterious members of the Oneg Shabbat; all that is known about him comes from the Archive (The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute).

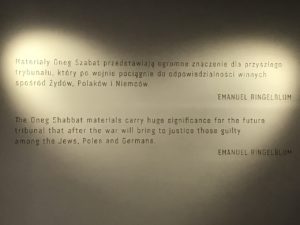

Ringelblum believed that Oneg Shabbat would run the risk of dehumanizing the Holocaust and Jewish-hettoization, if accounts like these were made inaccessible. Moreover, he believed that that risk was run if documentation revealed very few accounts like these too. He wished to assemble an archive with accounts of those from diverse backgrounds—from those involved with social activism, with education, with literature—for it would allow us a better understanding of the Holocaust, ghettoization (and of the Jewish community that endured them) altogether. It would have been so easy for Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat to have ceased archival work, if to protect themselves from Nazism; it would have been easy for them to have succumbed to fear, to worry, to doubt. Yet, they didn’t. The Oneg Shabbat was “…an order of brothers who carried a banner of readiness to make the ultimate sacrifice and to remain faithful in the service of society” (Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute). Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat continued to collect and preserve documents on Jewish subjugation and extermination, despite knowing that this would guarantee them further subjugation still. They resisted succumbing to fear, to worry, to doubt that archiving brought about, because they felt responsible for past and present Jewish communities. They felt responsible to risk their own lives, if for the sake of more appropriately commemorating theirs. And they felt responsible for future Jewish communities, whom they knew could learn from this history too.

“An Archive More Important Than Life.” Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute,

Warsaw. 2017.

Kostanian, Rachel. Spiritual Resistance in the Vilna Ghetto. Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, 2004.

“Ringelblum Archive.” Jewish Historical Institute, The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical

Institute, 8 Oct. 2014, encyclopedia.ushmm.org/tags/en/tag/youth?page=2.