Desecrated Graves: Tombstones and Selfies

By Aren Burnside

When examining history, there is often a struggle between remembering people versus remembering facts, especially when it comes to tragedies. I felt this struggle when visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau. Growing up in the United States, my education about World War II and the Holocaust were focused primarily on these facts. We were taught to remember that over 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. We were to remember dates, battles, and losses of soldiers. However, at Auschwitz-Birkenau our guide told us, “I want you to leave knowing the people, not the numbers and the facts.” Our focus was to remember the lives of distinct human beings, with names and everyday lives, that were killed there. At the end of the Auschwitz-Birkenau tour, I wondered how it could be that the population could forget those individual lives. The answer was not far away: people taking selfies on the railroad tracks into Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the rest of this short paper, I would like to argue that this casual defiling of graves contributes to the dehumanization of the victims and the erasure of their memory.

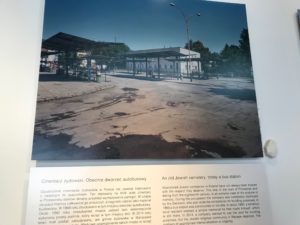

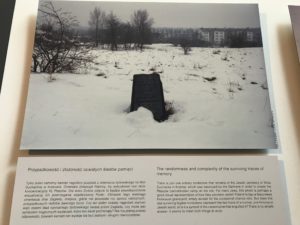

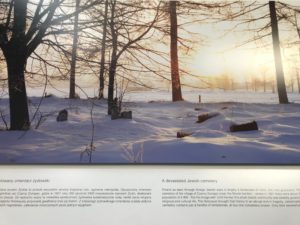

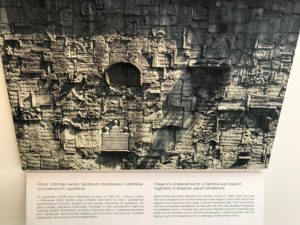

East and Central Europe has a history of grave defilement. In Vienna, our tour guide showed us where the gravestone of a Roman soldier had been used in building St. Stephen’s Cathedral. When visiting the Treptower Park in Berlin, our instructor mentioned that some of the stones for the park, if examined closely, were actually gravestones. Perhaps the greatest example of explicit grave desecration in East and Central European history was the destruction of Jewish cemeteries during the Holocaust. On the order of Nazi Germany, countless Jewish cemeteries were completely destroyed. Gravestones were removed from the ground and used for building, even for building the concentration camps that would soon hold living Jewish persons. For example, in Krakow, the Jewish Cemetery in the Podgorze neighborhood was destroyed by the Nazis and the stones were used to construct roads and the Plaszow Concentration Camp, which was built on top of the graveyard. Even regular citizens, as we learned at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow, looted Jewish cemeteries for gravestones and used them for building. The history of countless generations of Jews in Europe were erased. Now, these areas have been covered up, built over, and forgotten.

These actions all worked to erase the humanity of the individuals to whom the graves belonged. In Vienna, the use of the Roman gravestone to build the cathedral erases the soldier’s identity. The memory of the life of the soldier, which was likely not Christian, is rendered worthless; his gravestone is employed the same as any other stone used to construct the new Christian world. In Treptower Park, a similar fundamental dehumanization is occurring. To build the new Soviet World, the past and the humans who lived it are inconsequential. The Park itself held a modern and utopian feeling, as if pointing to the future. Looking to the new communist future didn’t require an intensive understanding of the past; instead, it required only an intensive understanding of the future and where

society was heading. Those whose gravestones were used here symbolize this: they are rendered stones good for building rather than representations of individual human lives that held great meaning in the past. As a small aside, in these situations I think it is important to understand these not as unintentional or unknowing actions. At least

for me, it seems intuitive that one does not simply pick up a gravestone, and through the entire building process, not notice that it bears the inscription of someone’s life. The gravestone either must be physically removed from the ground, or retrieved from somewhere else, in which case, an examination to make sure the stone would fit specifications would still reveal that this is indeed someone’s gravestone. Building with gravestones then, as I understand it, is a purposeful act in which someone knows that it is a gravestone, and still proceeds to build with it.

Nazi Germany brought a new wave of erasure to the scene on an unthinkable scale. Jewish cemeteries across Europe were decimated, erasing legacies, lives, and humanity. Those stones were used to build Nazi buildings and concentrations camps. Much like the former examples, this symbolically rendered Jewish lives unimportant. The Nazis’ use of these gravestones told Jews that the lives of their ancestors, and thus their lives, were worthless. The stones that still held the memory of these persons’ lives, though, was a practical resource that the Nazis refused to

pass on. Now, without these cemeteries, there is a gap in memory. How do you remember the human lives of people whose last identifier has been erased? The desecration of these gravestones not only render their owner’s life worthless, but also removes their presence from historical memory as a human being.

Imagine, then, the surprise one would find when visitors stand on

the train tracks entering Auschwitz-Birkenau, posing and taking photos. They would make sure that they have the right lighting, and when they found out they don’t, go back and strike another fanciful pose. I found this within the first few minutes of entering the larger Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Earlier in the tour, I watched visitors strike poses and take selfies with the “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work Makes You Free) sign as a backdrop. Late in the tour, I watched as one adult visitor, with headphones in, danced around, kicking around dirt. If one wanted to see such photos, you need only visit a social media site such as Instagram, type in #auschwitz, and scroll through the photos to find numerous selfies posted online.

Understanding Auschwitz-Birkenau as a graveyard brands these actions with special social meaning. I think most people would find it distasteful, to say the least, to take a selfie with a stranger’s gravestone or dance on a stranger’s grave. However, I will not be so bold to assume this is what makes these actions socially wrong. Rather, it is that these actions, much like the actions of those in the past who have destroyed graveyards and used gravestones for building, dehumanizes those who are remembered there. When one sees the

scenery or the railroad tracks as an aesthetic good, it has the same effect as those who saw gravestones as a practical or aesthetic good for building. One separates the actual human life that was lost from the physical object that merely holds that memory. For those that take selfies at Auschwitz-Birkenau, or other memorial sites, they see the space not as a graveyard full of the memories and histories of human beings, but as a landscape merely with an aesthetic appeal devoid of those memories. This attitude contributes to this struggle of remembrance of the Holocaust. People have become so disconnected from the actual lives of those killed that they are capable of taking selfies on their graves. This, in turn, disassociates them even further, as they become incapable of understanding the full meaning of the mass murder that occurred at this site. This act desensitizes the tragedy to the point where their fellowhumans’ lives are worth merely the opportunity for a photo shoot. The victims are reduced to numbers and facts rather than the human lives that they lived.

Those who died at Auschwitz-Birkenau did not choose it as their final resting place. Regardless, we should interact with the grounds as to take into account that this land is still their graveyard, and to treat it with disrespect dehumanizes those that lost their lives there. The desecration, though perhaps not as severe as ripping gravestones out of the ground, still disassociates the human lives that were lost from the physical thing that holds that memory. As such, when understanding this history of struggle and strife, we must not forget that it was human lives lost at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Humans who had dreams, had families, had memories, and had interests of their own. We must remember that this place is where those human beings rest, and that we must respect their memory as human beings as much as we would the grave of any other human being.