Auschwitz: An Experience and Lesson No One Should Ever Forget

By Meagan Edwards

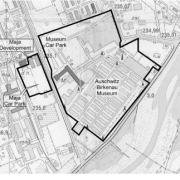

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, the former concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau, located in the town of Oswiecim in southern Poland, became the infamous universal symbol for the terrors placed upon the millions of victims, Jewish and non-Jewish, by Nazi Germany throughout the war. The systemic killing of Jews and other groups was an effort to cleanse German society of “non-Aryans.” The Nazi party was composed of members of the “Aryan race”, a race trumped up by the Third Reich in which according to Nazi ideology, constituted a German superior master race. This race was best fit for survival and “Non-Aryans” served as nothing but a hindrance to the survival of the Aryan race. “Non-Aryans”, essentially anyone of Slavic, “Asiatic” (a term used by the Nazi party to represent Muslim populations and people of central Asian heritage), as well as Jews, had to be removed. From the beginnings of the implementations of the Final Solution (the Nazi policy of exterminating European Jews) in 1941, Auschwitz-Birkenau became the largest extermination center designed to carry out the devastating policy.

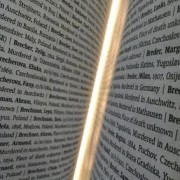

English inscription of the international monument located between the ruins of the gas chambers and crematorium 3 and 4 in Birkenau that reads “For ever let this place be a cry of despair where the Nazis murdered about one and a h

Although statistics vary, by the end of the war in 1945, Auschwitz was the location at which an approximated 1.3 million deaths by gassing, torture, starvation, and illness were carried out by Nazi commanders and SS officers. The deaths at Auschwitz account for an estimated tenth of the number of total victims of the Holocaust. Of the approximated 1.3 million victims of Auschwitz, Jews accounted for 90 percent. At the end of the war Poland once again became its own country. As a result of Soviet communist influence, Auschwitz became a museum commemorating the lives that were taken wrongly by the evils of fascism, and glorifying the Soviets as the liberator of the camp. It wasn’t until the collapse of communism that many historical inaccuracies were rectified by the Polish government and international scholars that Auschwitz became a place where the majority of its victims, were recognized as Jewish victims. With its newer accessibility to the west, Auschwitz became an onsite primary source for many scholars across the world studying Nazi policy and the cruelties in which the victims endured until their lives were viciously taken away from them. These scholars then spread the information to students studying the Holocaust. It became a place where Jews from across the world make a pilgrimage of sorts. A place that even surviving victims and family members go to memorialize the lives lost. Mostly it became a place where millions go who need to “see it to believe it” to understand the capacity of the Holocaust.

When visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau, one cannot expect to know how they are going to feel once they enter the main gate. Once inside, one still does not know exactly how or what they are going to feel with each step and with each site. While on a study abroad trip to the region of Upper Silesia, my peers and I were taken on a guided tour of Auschwitz-Birkenau. I would be lying if I said that the trip to this particular camp wasn’t what enticed me into taking the trip to study in Poland. The Holocaust is an event that I had been studying since my freshman year of college. As I enter my senior year in the fall, it is an event, no matter how much I learn about it, that I still cannot come to terms with. I believed that with finally visiting Auschwitz first hand, I could have a better and truer understanding of the horrors the victims faced every day. Prior to the visit to the camp I thought a lot about how or what I thought I was going to feel. I knew I would be sad for obvious reasons, but I was not sure of how I was going to be affected by each site. Walking into the main gate of the camp, the infamous entrance with the “Arbeit Macht Frei” sign situated above, an incredible stiffness came over my body. I was truly scared of what I was going to see, even though I already knew and have learned about it for three years. Walking the same path, that not even a century ago, the victims walked on to their inevitable death, made me numb. I attempted to hold myself together as the tour guide led us on. He brought us through the blocks that before the war were used as Polish army barracks, but during the war became a Nazi political prisoner camp, but eventually became a prison for anyone who the Nazis decided must be exterminated. He brought us through exhibits displaying statistics, prisoner documentation, and offices used as Nazi camp headquarters. I knew what was coming next, but at the same time I did not. I knew what I was going to see, but I did not know how it was going to affect me. We walked into the room displaying the hair of the women and men who were chosen to be immediately exterminated upon arrival. The Nazis, making use of every resource possible, used this hair, the hair of the people they had murdered, as a source of revenue, as well as uniform lining to keep their soldiers warm. Walking into the room I immediately wanted to walk right back out. My heart sank into my stomach and warm tears began to fill my eyes. Physically being in the presence of the hair I knew I was going to see, that belonged to innocent people, hair I knew that if it wasn’t for the advancement of the Russian army would have been gone and used as a resource, made me ill. I could not imagine the pure humiliation that these people felt, being shaved and stripped in front of thousands of strangers. Being a woman, my hair is a defining characteristic of my identity and I could never willingly part with it. The women in Auschwitz were forcibly stripped of this. A part of me felt guilty as I stared in the display case filled with hair. I could never truly understand what these people went through. No one, but the victims and the survivors, even if they choose to remember, can truly and wholly understand. The numbness carried forth as the tour continued.

We entered more rooms filled with the stolen belongings of the victims, which were also used as economic resources for the Nazis. As I attempted to gather myself together I looked in the opposite direction of the glass case covering the wall. On the other side of the room, a small display case sat, with a blue dress spread out next to shoes and toys that could not belong to anyone other than an infant. The heaviness I felt that I had been trying to mask, quickly haunted my body all over again. This time I physically began to cry. I pray that I will never have to experience being a mother and having to walk away from my child knowing that I will never see them again. I cannot understand how the SS officers, who had children of their own, idly stood by and carried out the orders of tearing children from mothers and murdering helpless and innocent people who haven’t and would never have to change to experience life. Reliving the experience as I write this paper, it still sends chills through my body.

Every single one of us was experiencing the same tour physically, but emotionally we all were faced by different inner challenges. Our tour continued, and the non-spoken agreement between us to remain silent carried out as went made our way into Birkenau. We entered, and walked along the train tracks where so many victims last breathed the last “fresh” bit of air they were ever going to breathe. It was on these train tracks where the mass deportees were forced to leave their belongings and loved ones, having refused would have been shot on the spot. Peering out into the distance, the vastness of the camp made me, a visitor only trying to understand, feel incredibly small. I was overwhelmed with anger and sympathy for the prisoners who were not given the chance to experience life outside the barbed wire electric fences ever again and for those who survived but still had to suffer inside.

Birkenau, built as an extension of Auschwitz, a deliberate effort to maximize the number of labor prisoners and to hold prisoners who would be killed. It is inside Birkenau, that resembles what one imagines a death camp to look like, but only worse. The barracks provide no protection from the outside elements. In the winter it was bitterly cold and in the summer it was excruciatingly hot. The “beds” (wooden platforms) layered over one another. Each level sized roughly eight by ten feet, was home to five or more people. The prisoners who were strong enough to climb to the top were at least protected from excrement and body wastes the ones in the lower levels were forced to endure due to starvation and gastrointestinal related illnesses. Prisoners too weak to climb to the upper levels were forced to sleep on the ground, exposed to infestations of rats and vermin. Disease ran rampant throughout the camp and also killed. Walking through the barracks I could feel my stomach turn, the thought of what was endured made me ill and cold.

Exiting through the barracks I looked out into the camp from the outside of the fence, because after visiting Auschwitz, I knew that even after this trip I would never come to terms and be able to understand the atrocities that were forced upon the prisoners inside. A monument was erected in Birkenau in the 1960s that paid homage to “the victims of fascism,” not mentioning the Jews specifically, but including them as victims by each nation. It wasn’t until the nineties when inscriptions of the monument were presented in Hebrew, Yiddish, and English to represent the Jewish lives lost and to pay respect to the survivors and surviving families who found their new home in America. The presence of this monument specifically was striking to me. Out of all of the lives lost and all of the nations impacted the Third Reich, persecution is still endured today, by those who are believed to be different or less than deserving. From having the opportunity to tour Auschwitz I have learned that no one but the victims and survivors can truly understand the horror of living inside the barbed wire. Although, we, as outsiders, can never truly understand the horror, it is important for everyone us to spread knowledge of the event to those who do not have access to such information. It is essential that every person whether they have had or have not had the chance to see Auschwitz in person to take the lesson and make others aware and be prepared to prevent such evil from having a chance to ever occur again.

All attached photos were taken by Meagan Edwards.